TORONTO

Most American film-industry types know that Oscar campaigning is a dance. One must spend six months flying to Q&As and luncheons to schmooze and glad-hand and demur when anyone mentions the O-word. It is the quest that shall not be named, because, as everyone knows, the worst sin of all is to show how much you want it.

The first time I met dissident Iranian director Jafar Panahi, though, he immediately broached the subject. “They just told me half an hour ago that 100 Iranian filmmakers and people of the cinema have gathered to write a statement and ask the government not to meddle with what film to send to the Oscars,” he tells me through his indefatigable interpreter, Sheida Dayani. “But it is very unlikely for it to happen.”

We’d seized the opportunity for a sit-down interview here, in a spare pop-up office at the Toronto International Film Festival — about a month before the acclaimed filmmaker’s 12th film, the Palme d’Or-winning “It Was Just an Accident,” would open in the United States — because no one was sure what borders the director would be able to cross, and when.

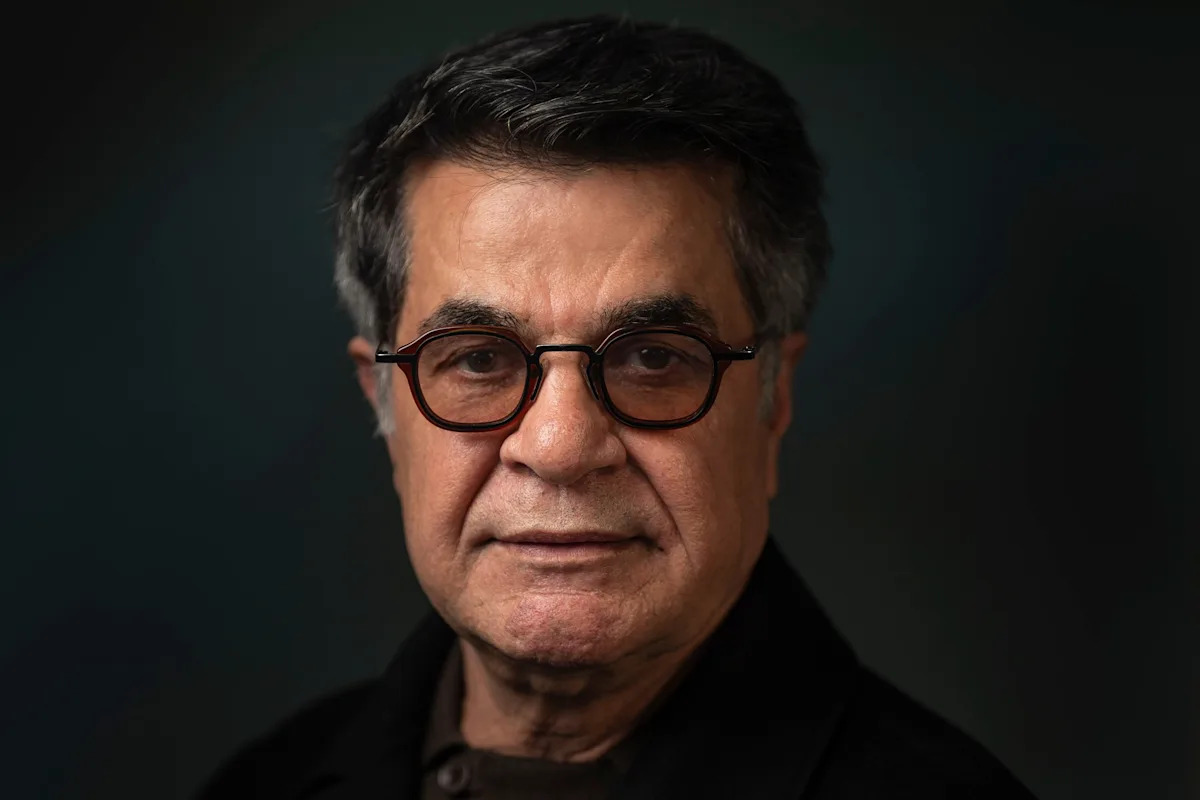

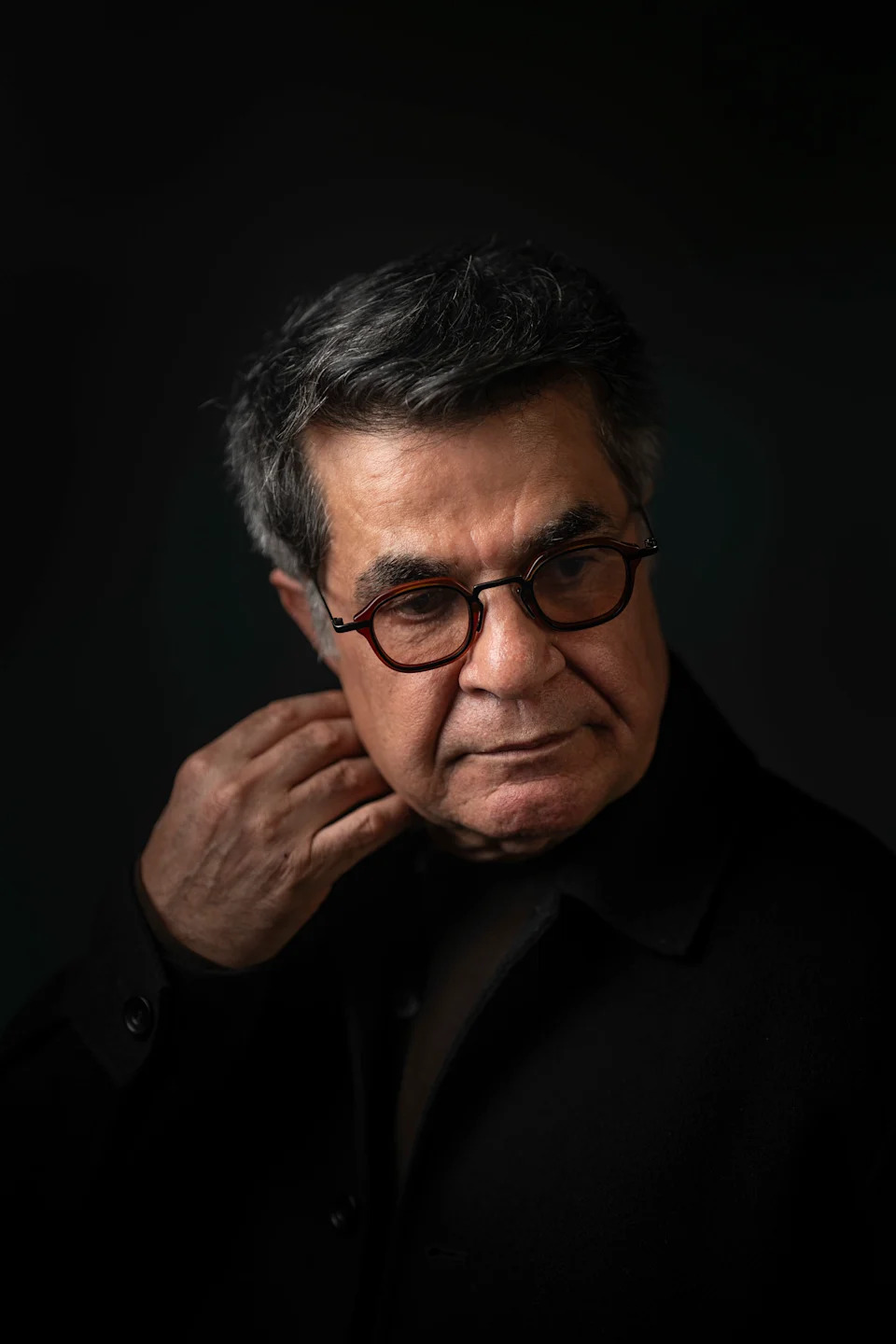

Panahi, 65, is one of Iran’s most famous former political prisoners — and also a captivating storyteller, with impeccable comedic timing that can belie his grim subject matter. Dressed in his trademark all-black uniform and dark tinted glasses, he was quick to flash a wry smile to telegraph his jokes even before Dayani jumped in to interpret. This is the first major press tour he has done in more than a decade, and I got the sense that he really wanted to be heard, even if it was one sentence at a time.

In 2010, the government arrested him on charges of creating “propaganda against the system,” held him in solitary confinement in Iran’s infamous Evin Prison and subjected him to near-constant interrogations.

It was the third arrest for Panahi — who had already won Venice’s Golden Lion for his 2000 film, “The Circle” — and it was life-altering.

He was released on bail after three months but was banned from making movies, traveling outside of Iran or speaking to journalists for 20 years. Hanging over him, too, was a six-year prison sentence that authorities could enforce at any time — which they did in 2022, while jailing other prominent filmmakers. Panahi would spend another seven months in Evin, getting out only after staging a hunger strike that sparked an international outcry.

The bans, which were finally lifted in 2023, didn’t stop him from directing movies, though. When you get such a sentence, Panahi says, “you really crumble within.” Then he went back to work, despite the clear risks to his safety, because, as he likes to joke, “I don’t know how to do anything at all apart from making films.”

His solution was to turn the camera on himself and film in secret, starting with the cheekily named “This Is Not a Film,” a self-portrait of his maddening legal battle that he’d filmed in his house; it was whisked out of the country for the 2011 Cannes Film Festival on a USB drive. For his 2015 film, “Taxi,” a lively snapshot of life in Tehran that won Berlin’s Golden Bear, he drove a cab and filmed his passengers. When the mournful “No Bears” premiered at the 2022 Venice International Film Festival, he was doing his second stint in Evin. In it, he plays a filmmaker named Jafar Panahi who travels to the Turkish border so he can direct a movie on the other side via video chat.

Panahi is now the only living director who has won the Palme, Golden Lion and Golden Bear — following the late Robert Altman, Michelangelo Antonioni and Henri-Georges Clouzot.

“The instinct of anyone making art, no matter the form, [needs to be], ‘If you cannot do this, will you be able to live?’” says Payal Kapadia, director of 2024’s lyrical ode to women, “All We Imagine as Light.”

“I don’t think Panahi could,” she says, “which is why he takes such risks to make his films.”

Any given filmmaker who’d just won the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival could expect to return home to a hero’s welcome. Instead, Panahi and his “It Was Just an Accident” cast and crew flew back to Tehran in late May not knowing whether they would get arrested.

They had, after all, made a darkly comic, often harrowing road-trip revenge thriller in secret, then smuggled the footage into France for postproduction. It’s a searing critique of the regime, based on Panahi’s experiences and stories he heard in prison.

“Perhaps if they had not put me in prison, this film would never have been made,” Panahi said at a Toronto Q&A. “So I was not the person who made this film. It was the Islamic Republic who made this film, and I’d like to congratulate them.” The room erupted in laughter and applause.

Set almost entirely in a van or in remote desert locations, “It Was Just an Accident” follows a ragtag group of former political prisoners who kidnap the guard they believe tortured them and destroyed their lives. Only they can’t be sure they have the right guy; they were blindfolded when the vicious Eghbal, or “Peg Leg,” tortured them. Soon, the spontaneous kidnapping turns into a mad caper and an impromptu tribunal as a bride, an auto mechanic, a photographer and a comically hotheaded taxi driver debate the necessity for revenge and just how violent it should be.

The last act’s pivotal scene is so emotional and unexpected, Martin Scorsese says he actually timed it (15 minutes). “I’ve never seen anything quite like it,” he told Panahi at a New York Film Festival talk in October.

This is the first film Panahi has made since his bans lifted. He says he went back behind the camera because his own need for introspection is less overwhelming. But his process still requires secrecy. To shoot in the open, he’d have to submit his script for government approval, and “we will not play the game,” he tells me.

He shot over 25 days because speed is one trick for not getting caught. There’s not a superfluous frame, even as the main action scenes are peppered with funny snapshots of Iranian culture, like a security guard who carries a credit card machine for bribes.

To keep the production under wraps, everyone involved had to fit in two cars. No one had a copy of the script, not even the cast and crew, who were only given pages and informed of shooting locations the night before. Panahi managed the shoot and the financing, scrounging up money as needed because he never knows whether police will stop him from finishing.

As with his other films, this one was made with mostly nonprofessional actors, with the exception of Ebrahim Azizi, who plays Eghbal. Panahi brought each of them over to his house — a cabdriver, a carpenter, a karate instructor — to read a partial script and gave them 24 hours to give him an answer.

On set, they carried fake scripts, in case anyone stopped them. The crew had stashes of fake props, fake cameras and blank memory cards as decoys.

“The secrecy of the film, in fact, makes it exciting,” says Maryam Afshari, the karate instructor who plays a wedding photographer, adding that the chance to be in just one frame of a Panahi film was worth the consequences.

“I myself have been beaten up on the street. I’ve been taken by the morality police, and many of us have been shot [with paintballs and rubber bullets] and questioned,” she tells me, emphasizing that negative attention is a way of life for outspoken women in Iran.

Panahi arranged it so the scenes he had to shoot in the city, where he was most likely to be recognized, came at the end. Sure enough, two days before wrapping, 15 plainclothes police officers raided the set to confiscate footage.

The team had prepared for this eventuality. Each day’s footage had already been copied, dispersed and hidden. The authorities rifled through a bag of dummy cameras and left after holding everyone for five hours. Still, Panahi shut down production for a month before a much smaller crew finished.

A friend snuck the final footage into France, where Panahi was teaming up with “Anatomy of a Fall” producer Philippe Martin for postproduction.

Then, just before Cannes, the female actors and director of photography were brought in for questioning.

“They were trying to convince me to wear a veil [hijab] on the red carpet,” Afshari says. “I told them, ‘Don’t you think it’s really silly that I show up in the film without a veil, and then you want me to go to a festival outside with a veil?’” (They told her that she was already facing severe punishment, perhaps up to 15 years in prison, but they’d lessen it if she cooperated at Cannes. She did not.)

“They were told, ‘You’re allowed to go, but please don’t go,’” Martin noted at a New York Film Festival screening of the film.

Martin said he believes that the spontaneous crowd of supporters that followed the Cannes win and the film’s international acclaim have “created a kind of protection around Jafar Panahi, his actors and his crew, and, for now, they’re able to continue having a normal life.”

The movie’s themes — of citizens being snatched off the street, of the resulting physical and psychic wounds, of how to fight back — have struck a chord with global audiences.

“It Was Just an Accident” has been in the Oscars conversation for best international feature ever since Neon (the distributor behind “Anora,” “Parasite” and “Anatomy of a Fall”) snatched it up at Cannes. As the race has since grown more defined, it’s now considered a nominations contender for best original screenplay, best director and best picture, too.

When Panahi brought up the Oscars with me, it was to rail against the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ antiquated rules for international feature submissions. Each country selects one film to nominate, which is a problem, he says, for Iran, China, Russia, India or anywhere that may silence voices.

For a dissident filmmaker, an Oscar is perhaps the biggest force field that exists — a kind of international rebuke to that government’s censorship.

“This,” he says, “is a form of resistance.”

After a thwarted attempt by Iran’s film guild to gain control of the selection process, the film is now France’s submission — a creative but controversial move given how many French-language films were passed over.

“I always wanted my films to premiere in Iran, and I really tried for that, but, so far, we weren’t able to make that happen,” Panahi says. “But later on, when the film goes on the internet, everyone immediately sees it.”

He smiles as he talks about his movie becoming a bootleg, eagerly reminding me that a DVD street hustler is one of the most memorable characters in “Taxi.” Iranian filmmakers don’t really get the luxury of caring about piracy or whether people see their films in 70mm or Imax.

So far, only 40 people in the country have seen it, he says, at a private screening at his home.

His favorite part of going to all these film festivals and screenings, he says, is being in a theater as a large audience reacts to his movie, because he has been deprived of that experience for almost 15 years. “It gives me a good vibe that I can relate to my audience,” he says.

Everywhere he goes, people ask him big political questions, but it’s hard to weigh in on any country except his own.

“I don’t know the language, and I can’t really hear people talking,” he tells me. “When I’m in my own country, I can get a sense based on what I overhear in public, and you can feel the lack of satisfaction and the discontent.”

He even tells me, not quite joking, that “it might be easier” if Iran decided to ban him from traveling again. “Because when I wasn’t leaving the country, I had more chances to think about what I’m going to do for my next film.”

“This,” Panahi says, “is a form of resistance.” – (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

Panahi grew up in a working-class neighborhood in southern Tehran, raised by a single mother after his father died from a heart attack at 53. He turned to movies because, as he told Scorsese, he was looking for God after his father’s death.

“I didn’t find God in the skies. I found God in images,” he said.

His worldview, his sensibilities, his humor are all tied to this country where the people live their lives amid corruption so pervasive that, as a kid, Panahi was expected to pass a small bribe to his teacher whenever he turned in a test paper.

His many filmmaker friends who now live in exile are far more “courageous” than he is, he told a crowd in Los Angeles in October. “I will always return home. I cannot be separate from Iran. … They have the ability to adapt themselves to another culture. I don’t.”

Panahi often draws sharp contrasts between his two extended stays in prison. In 2010, he’d been blindfolded and placed in a cell that measured about 5 by 8 feet. Alone and isolated, he could barely lie down. He was even kept blindfolded to go to the toilet.

He recalled interrogations that could last up to eight hours, blindfolded and seated with his face practically against a wall and his interrogator behind him.

“You’re very sensitive to the voice you’re hearing,” he tells me. “Your auditory senses become heightened, and you start wondering about your interrogator. How old is he? What is he wearing now? What does he look like?”

He continues: “Because you keep hearing this voice. You always ask yourself, ‘If I ever hear this voice outside prison, am I going to recognize it?’”

The next time, in 2022, was inspiring and motivating, in a strange way. He was amid a population of 300, 30 or 40 of whom were political prisoners like him. Most had spent half their lives in prison. He befriended them and listened to their stories just to pass the time.

Unbeknownst to him, the country had transformed in the seven months he was away. Massive protests for the Woman, Life, Freedom movement had broken out after a 22-year-old woman, Mahsa Amini, died in custody after being arrested by the morality police for allegedly not wearing her headscarf properly.

As soon as he left the prison, as amazed as he was by the energy in the streets, he felt an overwhelming burden, he tells me, knowing that he was outside and that his friends were inside.

Over the months that followed, he’d go by the prison and stare up at the walls, thinking about the stories he’d heard and the people he’d met — the violent person, the nonviolent person, the common worker — and the seeds of a movie began.

Panahi speaks with the authority of someone who knows that, as long as he lives in Iran, any protection the Palme d’Or (or an Oscar) provides is tenuous. A friend from Evin, journalist Mehdi Mahmoudian, who helped Panahi write the film’s propulsive penultimate scene, is already back in prison.

“In Iran, anything can happen at any time, not just in the world of cinema, but for anybody in any field, based on any excuse,” Panahi tells me.

He’ll be fine, though, he says, smiling and confident.

“What else is left for them to do?”