The FT has reported that Rachel Reeves is planning a “Budget tax raid on the owners of expensive homes”, expected to raise around £4bn. But less than a 20% of that revenue comes from homes in the top council tax band, while roughly 80% comes from the much larger group of homes in the second-highest band.

We’ve built an online calculator where you can test different council tax changes, so you can see how small changes affect total revenue – and what they mean for individual taxpayers.

This is an update of our previous article, which looked only at changes to the top band.

How much is raised? And from whom?

Council tax is based on 1991 property values, divided into eight bands from A to H. Band H is the highest – roughly homes now worth over £1.5 million – and Band G the next, typically £750k – £1.5 million.

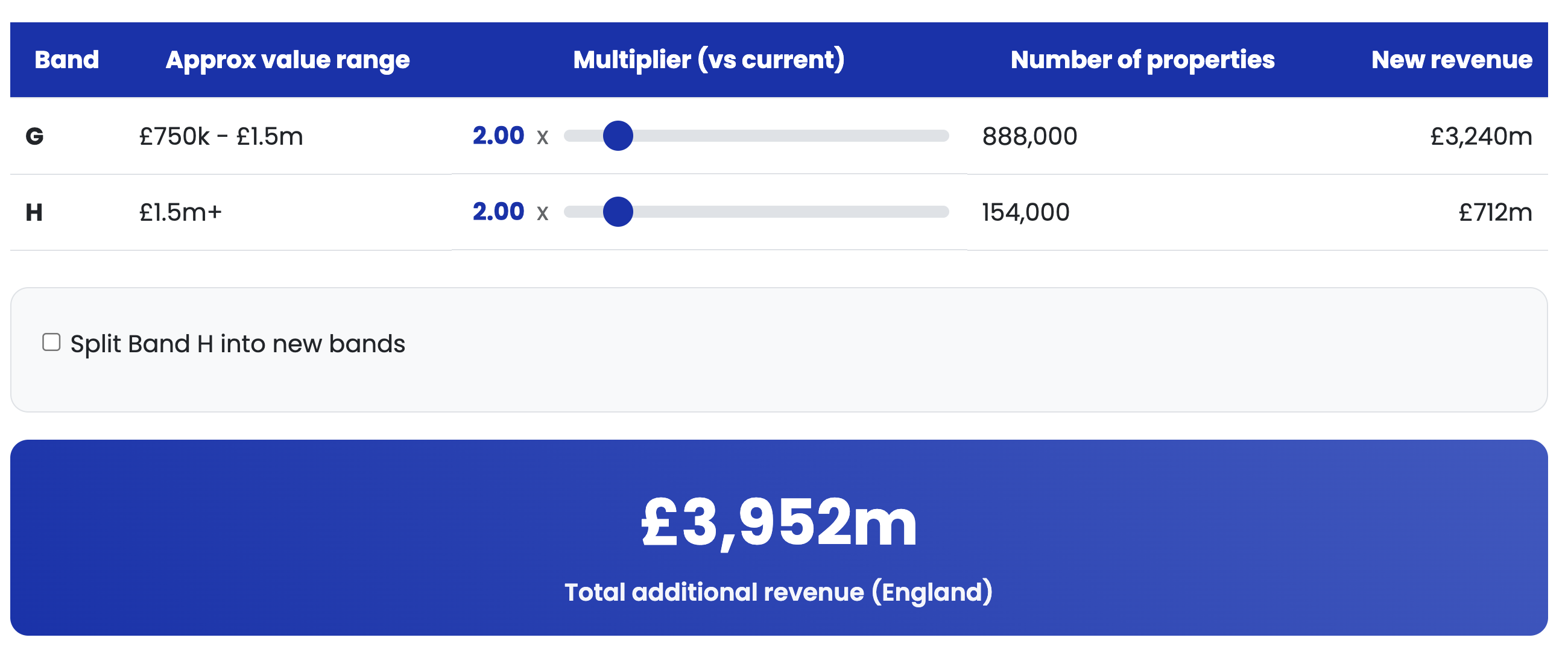

This calculator lets you experiment applying different rates to Band G and Band H (you can view it full screen here):

Your browser can’t display this interactive content. View it in a new tab.

Note that all figures here are for England. Scottish and Welsh council tax are devolved, and so the bands are slightly different. If applied across the whole of the UK, expect overall revenues to be 5-10% higher than those shown in the calculator.

What the calculator shows about the proposal in the FT

The simplest approach is the one the FT says the Government is considering – doubling council tax for Band G and Band H. You can model this in our calculator by setting the Band G and Band H multipliers to 2.0:

As the FT says, doubling both bands would raise about £4 billion – but more than three-quarters of that would come from Band G households. In practice, that means families in £750k to £1.5m homes would see their council tax double – an average rise of around £4,000.

The reason is simple: there are roughly eight times as many homes in Band G as in Band H.

Band H represents the UK’s 0.6% most valuable homes. Band G represents the next 3.5% most valuable – so we should expect in many cases people living in Band G homes earn £100k+. For those just in this bracket, that means £67k after tax (more if it’s a dual income household). A £4k tax increase is significant for them.

Council tax liability falls on occupiers – whether homeowners or tenants. In the long term, landlords rather than tenants bear the cost of council tax (because it reduces rents) but in the short-to-medium term all the cost falls on tenants.

Can we achieve the same result in a fairer way?

It seems intuitive that we could raise more money by leaving Band G alone, and instead adding new bands at the top.

You can test this in the calculator by clicking “split band H into new bands”. This creates three new above band H (you can change the values for each band using the slider).

You’ll see you have to apply an unrealistically high multiplier to these bands (increasing council tax bills five to ten times) to even approach the revenues achieved by a simple doubling of Band G and Band H council tax:

We can’t realistically expect people in £1.5m homes to pay a £25k council tax bill. This is not a sensible proposal.

What if we try a mansion tax?

We can achieve a fairer result if, instead of a multiplier, we apply a “mansion tax” to all the properties in Band H – i.e. a % of property value within the bands. That has a much reduced impact in those at the bottom of the band (say £1.5m to £3m properties) and a much higher impact at the top end.

You can see the impact of this in the calculator by clicking the “New Band H % tax” button. This then applies the set percentage to all property value within that band (on top of existing council tax).

However a percentage tax fails to raise as much as a simple doubling of Band G and Band H council tax unless we apply rates approaching and exceeding 2%:

Rates this high would in our view be unwise. They would be capitalised into property values (i.e. because people pay less for property that carries a liability). We estimate this effect would cause a 20%+ one-off fall in high end property values. This would have two consequences:

First, it would reduce SDLT revenues. This will be a large effect because of the disproportionate SDLT revenue from high value property. We estimate SDLT revenue could fall by around £2bn/year.

Second, it would be unfair to the current owners, operating in a similar way to a one-off property wealth tax.

There’s also a practical problem: creating a valuation system for applying a percentage tax to the c150,000 properties over £1.5m would require considerable resources (and take time to create). The council tax banding system was designed to avoid such difficulties.

So it’s easy to see why the FT says the Government is more drawn towards a simple doubling of rates.

The fairness problem

Our view is that it is absolutely fair and right to create new council tax bands at the top end and apply higher rates to them (provided we don’t set the rates so high that we see very significant declines in property value).

It does not, however, seem fair to greatly increase council tax for people in Band G. People living in Band G properties will often be comfortably off, but are certainly not the “super-wealthy”. In many cases they will have experienced significant tax increases over the previous ten years. It seems particularly unfair if any doubling will be cumulative on the second home premium, which doubles (and, in Wales, triples) the cost of council tax for people with a second home. A 600% premium would be unjust, and the impact on house prices would be so severe as to almost amount to confiscation.

Why is it that most of the tax increases of the last ten years have been on reasonably high earners and not on the super-rich? The obvious answer is the correct one: it’s much easier to raise large amount of money from them. There is no way to raise £4bn from the super-rich that’s anything like as easy as doubling council tax on moderately high value properties.

There are, however, relatively simple tax reforms that would raise significant sums from the very wealthy. For example: reforming capital gains tax, or making the previously-announced inheritance tax changes more effective. Or – even better – a wholesale reform of land taxation.

Methodology

We set out the methodology and limitations for our council tax calculator in our original article. The underlying sources are Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities data for most council tax statistics and Local Government Association data for the 2025/26 figure for each local authority.

The original calculator only applied to band H. The updated code, covering band G and band H, is available on our GitHub.

Photo of FT headline (c) The Financial Times Ltd, and reproduced here for purposes of criticism and review.

Thanks to C for assistance with the modelling.