Australians may be in for more wet weather with the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) index plunging to a record low. It’s a strong signal that wet conditions could be on the way for large parts of the country.

We’ve already had temperatures hit unseasonable highs for spring and damaging thunderstorms tore through parts of the nation’s east coast over the last week.

Giant hailstones, flash flooding, lightning and destructive winds wreaked havoc for millions.

So what’s coming now?

The Indian Ocean Dipole index could give a hint.

The IOD measures how warm the water is on one side of the Indian Ocean compared to the other and matters because it can indicate damaging weather patterns.

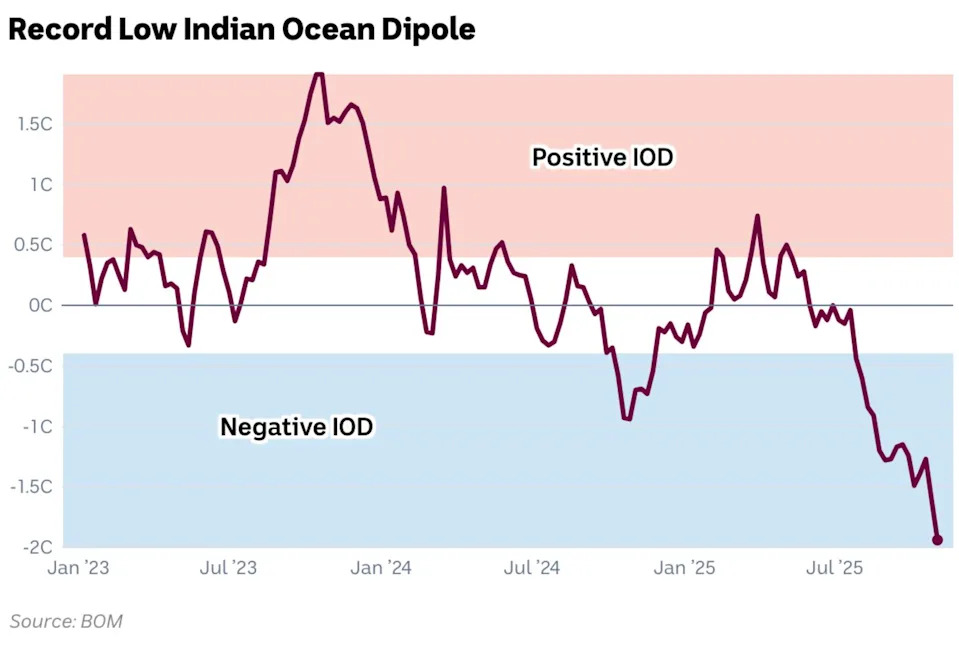

The Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) confirmed to Yahoo News the latest weekly measurement of -1.94 is the lowest in its database going back to 2008.

A negative reading means the waters near Indonesia and Australia are much warmer than usual, while those near East Africa are much cooler.

A strong negative IOD typically brings wetter, stormier conditions to southern and eastern Australia.

In simple terms, this record-low reading means the ocean could deliver more rain — and possibly flooding — to parts of the country in the coming weeks or months.

The Indian Ocean Dipole index has dropped to a record low of -1.94, the biggest dip in the BoM’s history. Source: BOM

Some parts of the country have been battered by giant hailstones. Source: Higgins Storm Chasing/ Dee

BOM senior climatologist Felicity Gamble said the IOD is similar in concept to the well-known El Niño and La Niña systems in the Pacific.

“The Indian Ocean Dipole is a little bit like El Niño and La Niña patterns, which are driven by the surface temperatures in the Pacific,” she told Yahoo News Australia.

“If we look at the Indian Ocean, which can also influence weather patterns in Australia, it can also have phases like El Niño or La Niña, but we call them negative IOD or a positive IOD.”

What causes a negative IOD?

Gamble explained that what’s happening now is a clear case of contrasting extremes between the two sides of the ocean.

“At the moment we’re seeing really warm conditions in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean and cooler than average conditions in the western tropical Indian Ocean,” she said.

“This causes a broad-scale shift in the atmospheric patterns, and that therefore can influence our rainfall and temperature patterns across Australia too.”

Several factors have helped drive this particularly strong event.

“We have seen a sudden cooling in the western Indian Ocean, around the Horn of Africa, due to tropical activity,” Gamble said.

“Often when we see tropical lows or cyclones developing in that part of the world, it does tend to have a cooling effect at the surface of our oceans.

“We’ve also seen very warm conditions off Asia, which sets up a change in the atmospheric circulation, so we tend to see more cloud developing in our regions and more rainfall associated with that.

“That could be spread across Australia.”

What does this mean for Australia?

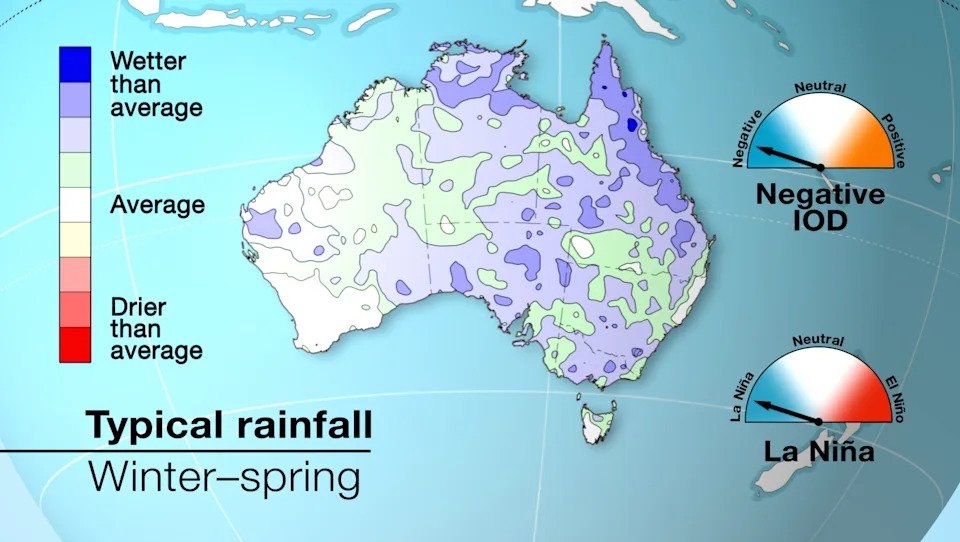

The impacts could be widespread — stretching from northern Western Australia to Victoria.

“We can see that influence in parts of northern WA, and it can also extend into central parts and even as far as southeast Australia, so across Victoria and that sort of thing as well,” Gamble said, adding that previous strong negative IODs have brought some of Australia’s wettest periods in recent history.

“In 2016 we had a negative IOD and that was quite a significant year — we got quite a lot of rainfall, very much above average rainfall during winter and spring of that year,” she said.

“When we see the opposite phase, so the positive phase, we generally see below average rainfall.

“A good example of a positive phase was 2019, [which] was particularly dry across much of Australia and that led into Black Summer and those very widespread bushfires.”

While some have wondered if a developing La Niña could combine with the IOD to bring even more rain, Gamble said the outlook is more nuanced.

“Our model takes into account the influence from not just the Pacific and whether we’re in El Niño or La Niña, but also the Indian Ocean as well as the sea surface temperature patterns more locally around Australia,” she said.

“They all interact with each other. So we have to be careful not to just say, ‘we’re seeing a developing La Niña and therefore that means it’s got to be wet,’ because it’s not just these particular drivers that influence our rainfall.”

Typical winter-to-spring rainfall during a La Niña season combined with a negative IOD. Source: BOM

But it may not be rainy everywhere

Despite the wet signal from the oceans, BoM’s long-range forecast isn’t uniformly rainy everywhere.

“At the moment we are seeing a little bit of a wet signal across parts of southern Australia, but we’re actually seeing drier than average conditions forecast for parts of the west and parts of the Northern Territory as well,” she said.

“So while we are seeing some wet signal coming from the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean, there’s also something else going on that’s producing a dry forecast in some areas and no particular signal in others.”

And the good news is, the current IOD pattern won’t last forever. “Indian Ocean Dipole events generally weaken quite rapidly in summer,” Gamble said.

“All our model forecasts are in agreement that from about December we’ll see a rapid weakening of the negative Indian Ocean Dipole.”

Do you have a story tip? Email: newsroomau@yahoonews.com.

You can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Twitter and YouTube.