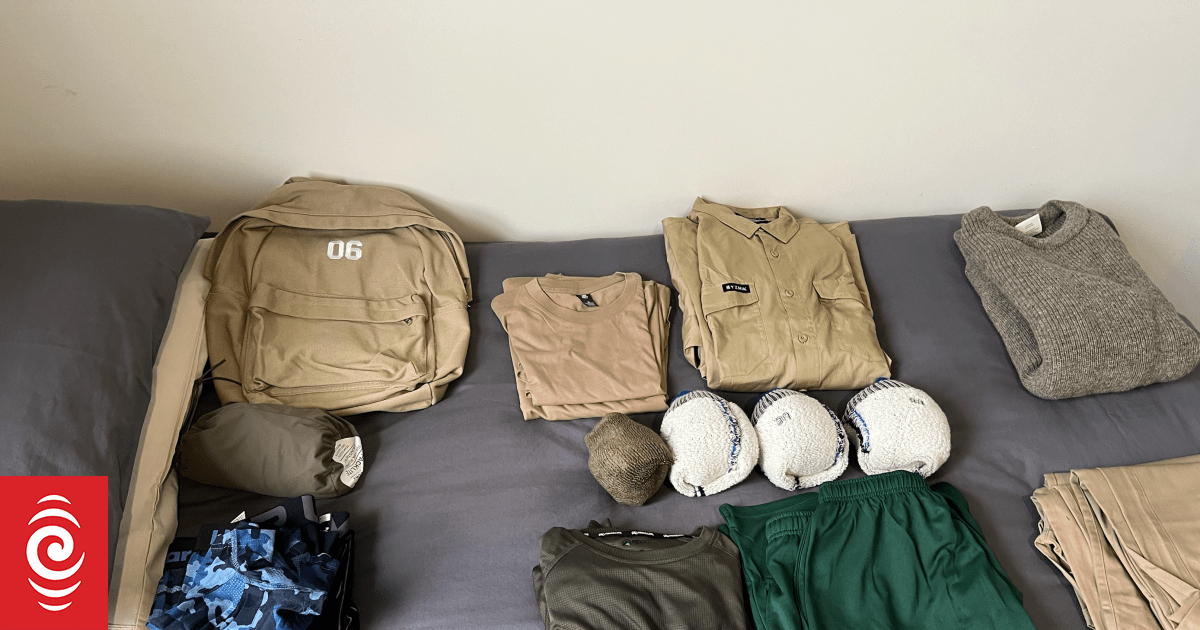

An example of the military style uniform the youths in the pilot were required to wear.

Photo: RNZ / Rachel Helyer-Donaldson

The final evaluation for the government’s military-style boot camps found it was too small to provide any meaningful data, and its implementation was rushed.

The 82-page report says the pilot contributed to “meaningful and positive change” for the young people involved, while acknowledging the cohort was too small to draw firm conclusions. It also highlighted a range of barriers and challenges to achieving outcomes.

Those barriers included rushed implementation, challenging transitions, a lack of continuity around therapeutic support, a lack of capacity in the residential phase, and support for whānau began too late before the rangatahi returned home.

It also noted the efforts to include te ao Māori and te reo Māori were valued but “didn’t go far enough” given” all the MSA pilot participants were rangatahi Māori and several were fluent te reo Māori speakers.”

It wouldn’t publish the overall reoffending rate, but said the majority of the MSA cohort reoffended within two months of release into the community.

The pilot programme for a cohort of the country’s most serious offenders aged between 14 and 17 started at the end of July in 2024, and finished in August 2025. During the pilot participants ran away, one was kicked out of the programme and another was killed in a three-vehicle crash.

The military style academies for youth had also come under scrutiny by opposition parties for a lack of transparency, particularly the reoffending rate of the teenagers. Reducing reoffending was a primary goal for the boot camps.

Seven of the 10 young men involved in the controversial military-style academy (MSA) boot camp pilot reoffended, according to Oranga Tamariki.

The final report summarised evaluation findings for the full pilot and focused on planning, implementation, to what degree the MSAs contributed to meaningful change, and what key factors should be included in future programmes.

Information for the report built on interviews previously conducted, and data collection took place during the final three months of the community phase, between June and August this year.

The participants themselves were all male, all were Māori, and two also had Pacific and New Zealand European ancestry, most were 17 years old with two younger participants (14 and 15).

Six out of ten of the young people had ADHD either diagnosed or suspected. Three of those diagnosed were unmedicated. Other learning difficulties among the cohort also included auditory processing challenges for example.

Mental health issues were noted for several young people including difficulty regulating emotions, anxiety, suicidality and PTSD. Almost all had substance abuse noted in their assessments.

The findings

The report asked “to what degree did the MSA pilot contribute to meaningful change?”

It stated the pilot had been successful in “testing new ideas” and “generating learnings” relevant to other Youth Justice Residences and future programmes.

“Overall, evidence from qualitative interviews, clinical assessments and reoffending data indicate MSA has contributed to meaningful and positive change for rangatahi.

“Reductions in frequency and seriousness of offending were potential changes in the trajectories of MSA rangatahi and showed progress towards longer-term outcomes.”

It noted, however, longer term follow ups were required as well as a higher number of participants to “confirm conclusions about effectiveness.”

It also listed a range of barriers and challenges to achieving outcomes and a sustainable programme. These were:

Insufficient time for implementation: Short timeframes impacted the translation of the MSA design into implementation. Their impact was evident in kaimahi working to design the residential phase as they delivered it, the extraordinary effort required to deliver the residential phase and the pressure on kaimahi. Preparation for transition and whānau support began late which impacted the quality of transitions and preparation for rangatahi in the community. Timeframes also meant social workers were not involved in the residential phase or adequately prepared for their roles in supporting rangatahi in the community.

Transitions were a challenge: Transitions represented a large shift away from a highly structured environment with minimal risks to a less structured environment where risks like mates, social media, drugs and alcohol were present. Intensive support through the transition period addressed the risks but a step between the residential phase and community phase like supported living could further reduce risk.

Continuity of therapeutic support: Lack of continuity of therapeutic support also meant work focusing on criminogenic factors could not continue in the community phase. Continuation of therapeutic support was not clearly assigned to any role though Oranga Tamariki expected some support to be provided by mentors and social workers. However, capacity and clinical skills limited the extent mentors and social workers could provide therapeutic support.

Clinical capacity in the residential phase: The clinical team could not deliver the planned individual interventions in the residential phase due to insufficient capacity. Additional clinical capacity would also have strengthened transition planning.

Whānau intervention: The need to support whānau to provide a positive environment for rangatahi in the community was highlighted in the MSA design but support began too late in the residential phase for significant change to be made before rangatahi returned home.

The report acknowledged that allowing more time for the design could have “strengthened” the pilot implementation, and would have “allowed the design to be fully realised in implementation.”

RNZ revealed last year the pilot programme was still in its design phase the month before it was due to start.

“The short timeframes for design and implementation limited the extent some of the key elements of the MSA design could be fully realised including transition planning, preparation for the community

phase, and whānau support,” the report stated.

“Timeframes therefore also limited the extent the evaluation could reach conclusions about the MSA design and implementation.”

The report also said the cultural elements of the design could be “strengthened to better meet the needs of rangatahi Māori.”

Efforts were made to include te ao Māori and te reo Māori in the bootcamp, and those efforts were valued the report stated, but “they did not go far enough given all the MSA pilot participants were rangatahi Māori and several were fluent te reo Māori speakers”.

“Building MSA on te ao Māori rather than adding components in may have strengthened the fit with the MSA cohort and increased engagement.

“Rangitāne iwi, although experienced in youth justice support, were not included early in the design process. Involving tangata whenua in the design earlier would strengthen both cultural and other aspects of the programme and increase the focus on te ao Māori.”

RNZ revealed last year Oranga Tamariki had acknowledged it should have engaged with mana whenua earlier in the process.

On transitions, an “early challenge” were delays in preparation of living environments and the physical needs identified in transition plans.

The report indicated failure to provide the needs identified in the transition plans “eroded rangatahi trust as they felt like ‘broken promises’.” Stakeholders blamed a lack of funding availability.

Some aspects of unprepared plans were described as a lack of basic essentials.

“Rangatahi moving into independent living found that when they arrived their accommodation was not prepared with the necessities such as food for the first days, furniture, plates and cutlery. Internet connections took weeks to be arranged in some cases.”

The evaluation drew on data from psychometric assessments, interviews with kaimahi, rangatahi and whānau, and Oranga Tamariki analysis of Police proceedings data.

“All sources showed indications of positive change for the MSA cohort. Larger numbers and longer-term analysis are needed to draw stronger conclusions about effectiveness.”

The positive changes that were demonstrated included involvement in education, work experience and employment, as well as improved wairua (spiritual), physical and mental health, reconnection with whānau and stable living situtions.

The Minister in charge, Karen Chhour

Photo: RNZ / Angus Dreaver

Reoffending

The minister in charge, Karen Chhour, has consistently backed the pilot, saying it was about giving young people a chance. Chhour has also said future programmes would take on board what had worked well in the pilot, and learn from what hadn’t worked well.

Chhour rejected the notion reducing reoffending was a primary objective, saying the primary objective was to try stop young people entering the correction system.

Following the death of one participant in a car accident – and another escaping from custody, who then went on to allegedly reoffend alongside a third participant – Oranga Tamariki announced they would only provide public updates “at appropriate times through the community stage.”

Military-style academy programmes lead Janet Mays said, going into the pilot, Oranga Tamariki was “realistic about the likelihood of re-offending”.

“We have previously confirmed that seven of the participants re-offended to a threshold that required them to return to residence for a time.

“One of our key aims was to see a reduction in the frequency and severity of offending by these rangatahi.”

The report stated the overall reoffending rate wouldn’t be included because “Oranga Tamariki protocol is to not cite any statistics that have the potential to identify a young person.”

However, the report noted the majority of the MSA cohort reoffended within two months of release into the community, but it said there were “positive differences” to the matched Supervision with Residence (SwR) in a Youth Justice Residence cohort, a group of rangatahi with similar characteristics and offending history.

Comparing the six-months before the residential phase to the six-months after release showed:

Time before reoffending increased: MSA rangatahi were slower to reoffend compared to the matched SwR cohort.

Seriousness of offending decreased: Two-thirds (67%) of MSA rangatahi reduced the maximum seriousness of their offending compared to only 22% of the matched SwR cohort.

Violent offending reduced: (including robbery-related offences and injury causing acts) by MSA rangatahi reduced by two-thirds (67%) in the six-months after exiting residence compared to the six-months before entering residence.

Combined view of reoffending results: Five (59%) of the nine rangatahi on the MSA pilot reduced the frequency, total seriousness and maximum seriousness of their offending compared to only two (22%) of the nine matched SwR cohort.

In terms of the reoffending itself, some was considered minor with “some more serious.” Many of the teenagers had described how hard they tried to stay out.

“I tried to change but f**k it’s hard … I tried to stay out, but it didn’t last very long,” one said.

“I always think I’m not going to get caught. I know I can stop. I was a dumb c**t then, when I was 13. I’ve matured since then. Everyone always regrets what they do. I do a little bit. Got some money, clothes, shopping. I don’t get the adrenaline rush anymore. I get paranoid,” another said.

A small number of the cohort didn’t return to a Youth Justice Residence, and this was seen as an achievement for the MSA.

Finally, the report acknowledged the “stable cohort” of rangatahi in the MSA had contributed to safety in the residential phase and supported the therapeutic focus. It said there were no fights between rangatahi or with the workers in the residential phase.

“This result was markedly different from other Youth Justice Residences where physical conflict between rangatahi or with kaimahi were regular occurrences.”

MSA programmes lead Janet Mays said the pilot aimed to help a “small group of serious and persistent young offenders turn their lives around, by giving them increased structure and support through an intensive intervention. “

The “full wraparound programme” combined therapeutic care, intensive mentorship and whānau engagement.

“The young people were encouraged to develop new skills, and move into education, training or employment.”

Minister responds

Chhour said the findings from the independent report showed “why it was an important and worthwhile pilot”.

She said the reality for young serious offenders was a “pathway to adult Corrections” and a lifetime in and out of incarceration, “unless they are given a chance to turn their lives around and take that chance”.

“This programme has been that chance.”

She said the data was clear that two of the nine young people had not reoffended, and the majority of the nine young people were currently in the community. She said they re-offended during the pilot phase, but had “not done so since.”

“All of the nine young people expressed a desire to not reoffend and have been taught greater coping skills and provided with mentorship.”

Chhour said the government was reviewing the pilot while it was operating, and had taken on “learnings” from its successes.

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.