The last trip of the season for the Edmund Fitzgerald was supposed to be a week before the storm

At least six of the crew of 29 planned to retire after the fateful trip

The song about the shipwreck was a fluke and was almost not recorded

It’s been 50 years since the Edmund Fitzerald sank in Lake Superior, taking the lives of all 29 aboard. There have been multiple books written about the tragedy, along with the famous song by Gordon Lightfoot. Yet there are many things about the boat, the cause of the sinking and the crew that remain surprising.

Bridge Michigan recently spoke to Michigan native John U. Bacon, author of the new book “The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

Here’s what surprised him about the disaster on Nov. 10, 1975 amid 25-foot waves and 80 mph winds, about 17 miles north of Sault Ste. Marie.

The Edmund Fitzgerald was famous even before the tragedy

Bacon called the ore carrier a “rock star,” that drew large crowds at the Soo Locks when it traveled through.

Related:

“It was for a long time the biggest, one of the fastest, (hauling) the most cargo,” he said. “It broke every record in the Great Lakes for one trip for a season, and it did it repeatedly up until the ‘70s.”

The Great Lakes are more dangerous than the Atlantic Ocean

Salt water turns ocean waves into “a soft roller coaster,” Bacon said, while Great Lakes waves are pointy and closer together, making storms more deadly for boats of all sizes.

“There (were) 6,000 Great Lakes shipwrecks between 1875 and 1975, one a week on average. That’s one a week for 100 years,” Bacon said. “Thirty thousand men and women drowned.”

But since the Fitzgerald went down, no commercial ships have been lost on the Great Lakes. Weather forecasting has improved, and shipping companies are more cautious.

It was supposed to be the last trip for six of the crew

The fateful trip that began Nov. 9 in Superior, Wisconsin, was going to be the last load of iron ore pellets before retirement for 63-year-old Captain Ernest McSorley. “At least five of his colleagues, his buddies, were going to retire also,” Bacon said.

On a balmy November day in Duluth, Minn., the captain of the Edmund Fitzgerald embarked on his last voyage before retiring. One day later, as a Canadian songwriter was struggling to find the words for a sea shanty he was writing, that ore freighter was being tossed around on 30-foot waves in Lake Superior. Nov. 10 marks the 50th anniversary of the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald. All 29 sailors aboard were killed in a massive storm, a tragedy that was immortalized in a song by Gordon Lightfoot. Michigan native and New York Times best-selling author John U. Bacon’s latest book, “The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” chronicles the story of the ore carrier, from construction to its final tragic trip, interviewing family members and sailors who had worked on the ship before the wreck. The book offers details of the ship, crew and sinking that surprised even the author, who has been fascinated by the Edmund Fitzgerald since childhood. “Trust me,” Bacon told Bridge Michigan, “90% of this has not been told before.” Read more of the interview at the link in our bio. #michigan #history #edmundfitzgerald #shipwrecks #greatlakes

♬ original sound – Bridge Michigan

Another crewmember found out just two months earlier that his girlfriend was pregnant.

Medical bills were the reason the boat was on Superior that night

The Fitzgerald’s last trip for the season was supposed to be one the ship made a week earlier.

But McSorley “tacked on one more, because he would get a nice bonus. He needed that bonus to pay for his wife’s health care,” Bacon said.

A decision to take a “cautious” route backfired.

Knowing a storm was approaching, the Fitzgerald’s captain chose a longer, northern route across Lake Superior on his trip bound for Detroit’s Zug Island, believing it would avoid the worst of the storm.

But the longer route allowed more time for the storm to build. By the time the ore carrier was struggling and ultimately failing to reach the relative safety of Michigan’s White Fish Bay, waves were 25 feet to 35 feet high.

The song about the tragedy almost didn’t happen

The recording of “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” was a fluke. Canadian songwriter Gordon Lightfoot had penned the lyrics to the tune of a sea shanty, but only recorded it because he had extra time reserved at a recording studio after finishing all his prepared songs.

Related: What are the iconic Michigan songs? Here’s Bridge’s playlist. What’s on yours?

“The producer says, ‘Why don’t you try that sea shanty you’ve been messing with?’” Bacon said. “They finish 6 ½ minutes later, … and they kind of look around, go, ‘Wow, that wasn’t half bad.’

“The song you hear on the radio is (a recording of) the first time it was ever played.”

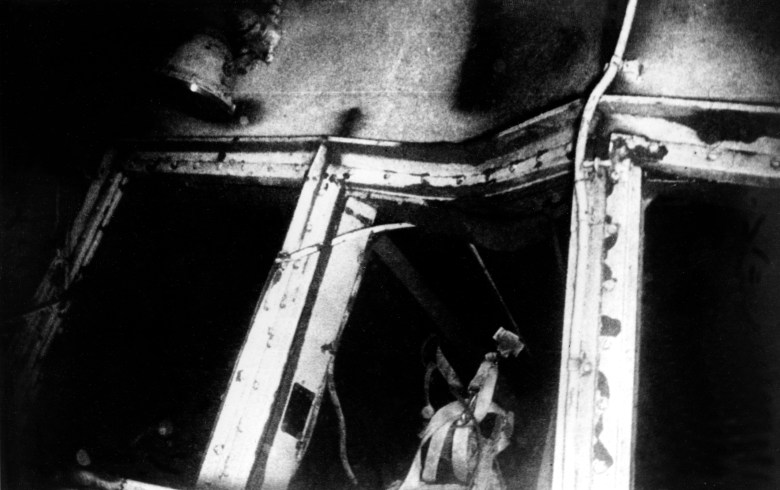

This underwater photo of the sunken SS Edmund Fitzgerald was taken by an unmanned submersible robot, as a research team investigates the wreck site 17 miles northwest of Whitefish Point in 1989. (AP Photo)

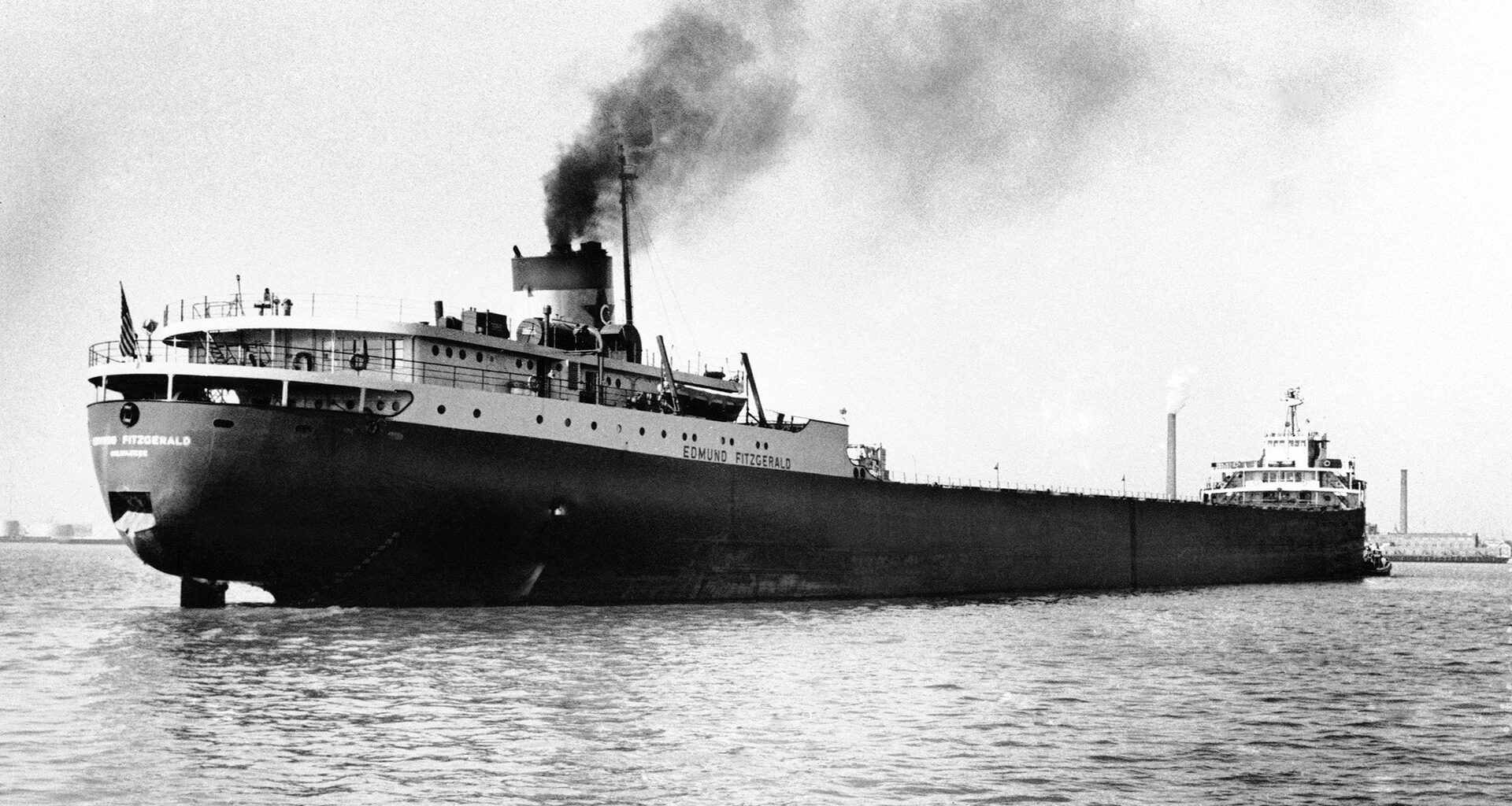

This underwater photo of the sunken SS Edmund Fitzgerald was taken by an unmanned submersible robot, as a research team investigates the wreck site 17 miles northwest of Whitefish Point in 1989. (AP Photo) The largest and longest vessel ever built on the Great Lakes, the 729-foot ore carrier SS Edmund Fitzgerald, slides into the launching basin, on June 7, 1958, in Detroit, Michigan. (Associated Press)

The largest and longest vessel ever built on the Great Lakes, the 729-foot ore carrier SS Edmund Fitzgerald, slides into the launching basin, on June 7, 1958, in Detroit, Michigan. (Associated Press) Two U.S. Coast Guardsmen move a life raft from the freighter Edmund Fitzgerald across the dock in Sault Ste. Marie, Nov. 11, 1975, after the raft was plucked from Whitefish Bay by the freighter Roger Blough, a ship assisting in the search for the missing Edmund Fitzgerald. (AP photo/JCH)

Two U.S. Coast Guardsmen move a life raft from the freighter Edmund Fitzgerald across the dock in Sault Ste. Marie, Nov. 11, 1975, after the raft was plucked from Whitefish Bay by the freighter Roger Blough, a ship assisting in the search for the missing Edmund Fitzgerald. (AP photo/JCH) In a Nov. 24, 1975 file photo Coast Guard officers on a Board of Inquiry inspected life rings that were recovered from the ore carrier Edmund Fitzgerald. (Associated Press)

In a Nov. 24, 1975 file photo Coast Guard officers on a Board of Inquiry inspected life rings that were recovered from the ore carrier Edmund Fitzgerald. (Associated Press) This 1976 underwater photo shows a close up of the pilot house of the freighter Edmund Fitzgerald after it sank at the bottom of Lake Superior. (Associated Press)

This 1976 underwater photo shows a close up of the pilot house of the freighter Edmund Fitzgerald after it sank at the bottom of Lake Superior. (Associated Press)

The families no longer care how the ship sank.

There are many theories about what happened that night, from scraping the hull along a shallow patch near Caribou Island, to hatchways not being sealed properly, to the overwhelming impact of a freak storm.

While the mystery intrigues the public, family members of the crew told Bacon they no longer care how the ship went down.

Few of the families knew each other before the sinking. In the decades afterward, they’ve become a tightknit group.

Related

Thank you to our Bridge Michigan Outdoors sponsors

Bridge Michigan Outdoors is made possible by generous financial support from our sponsors. Please visit the About page for more information and to subscribe to Bridge Michigan Outdoors. Interested in becoming a sponsor? Contact Emma Carr.

Republish This Story