In Britain, a November dusting of snow is an aberration. In Ukraine, it is the beginning. Soon pavements will ice over and the Dnipro river could freeze thick enough to walk across.

And General Winter, as Moscow knows, changes everything.

In successive centuries, against Napoleon and Hitler, Russia counted on the big freeze to alter the course of conflict. Today, Vladimir Putin is hoping the year’s bleakest months will mark a breakthrough in a war whose costs in men, money and materiel have become ever more grotesque.

Already, the Russian president’s enemy in Kyiv is on the back foot on three fronts.

Diplomatically, Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky has been frozen out of the Trump administration’s 28-point peace plan, which would reportedly hand the Donbas to Russia.

Militarily, Zelensky’s forces are losing ground.

And on the home front, the Ukrainian president is hemmed in by an energy-sector corruption scandal that could not be more politically damaging.

For the past month, residents in Kyiv have been subject to rolling blackouts. Eight to 10 hours a day without electricity is the norm. Usually, residents are notified well in advance and can plan to sleep, sit in a café or otherwise occupy their hours offline.

Russian strikes on energy infrastructure are leaving Ukraine’s streets dark at night – Maksym Kishka/Frontliner

But as temperatures dip towards zero, blackouts turn from inconvenient to intolerable. Zelensky knows that for the fourth year in a row, Russia will try to recruit General Winter to crush his nation’s resolve.

This year is set to be the worst of all. Will it be the winter that finally cracks Ukraine?

Home front: The war on warmth

There is logic, but not subtlety, to the Kremlin’s winter-warfare strategy.

Using missiles and drones, it blasts energy infrastructure with the goal of making the basic functions of existence – heating, running water, electricity, sanitation, even commercial food supplies – impossible.

The central threat is literally to freeze civilians. In Ukraine – as in Russia – most residential buildings depend on hot water pumped from power stations. Damage the power stations and entire city districts are left without central heating.

Civilians are evacuated from Druzhkivka in the Donetsk region on November 12 – Maria Senovilla/EPA/Shutterstock

They can usually be repaired. But if a strike knocks out a city’s thermal power and heating plants for more than three days when temperatures fall below minus 10C, energy expert Oleksandr Kharchenko warned this month, the capital faces a “disaster”.

Whole buildings – districts, even – would simply become freezers. Urban areas, he warned, needed to come up with back-up plans to work out how residents would survive. What those plans might look like is unclear.

What is clear is the scale of the onslaught.

A huge drone and missile strike on Ukraine’s energy grid on the night of Nov 8 temporarily knocked out at least three power stations – two thermal plants in the Kyiv and Kharkiv regions and the Kremenchuk hydroelectric plant on the Dnipro river – and forced eight to 16-hour power cuts across most of the country. Previous mass strikes on energy came on Oct 10 and 22.

Battlefield analysis suggests the Russians seem to be concentrating on energy infrastructure in the eastern half of the country, aided by the ready availability of cheap Shahed drones, which allow Russia to strike relatively small targets, such as electricity substations, that it would rather not use expensive missiles on.

An employee inspects a thermal power plant hit in a recent Russian missile strike, at an undisclosed location in Ukraine on November 13 – REUTERS/Gleb Garanich

It is not just electricity transmission that is being targeted, but the fossil fuels that generate it.

On Oct 3, Russia struck Ukraine’s main gas fields in the Poltava and Kharkiv regions, knocking out some 60 per cent of domestic gas production.

In August, more than 100 miners had to be rescued from their pit after Russia targeted a coal mine in Dobropillia, one of the last major Donbas coal producers in Ukrainian hands. The Pavlohrad coal field, outside the city of Dnipro, suffered a series of strikes last month.

The energy war has been relentless.

Front line: The war on morale

However miserable the home front gets, it is a safe bet that a winter in the trenches is worse.

Breath freezes in your nostrils. Beards and moustaches become festooned with icicles. Toes go numb, no matter how many layers of socks. Fatigue and hunger build quickly because the body is constantly burning calories to stay warm.

Kit, too, has to work harder in the cold. Batteries – so crucial to this tech-driven, drone-dominated war – die rapidly.

Terrain sheds all its comforts. Natural cover vanishes as the leaves fall – the difference between the impenetrable verdancy of treelines in summer and their nakedness in winter needs to be seen to be appreciated.

At least when the latrine freezes, it stinks less.

As winter begins, Russia is pressing forward in three key areas.

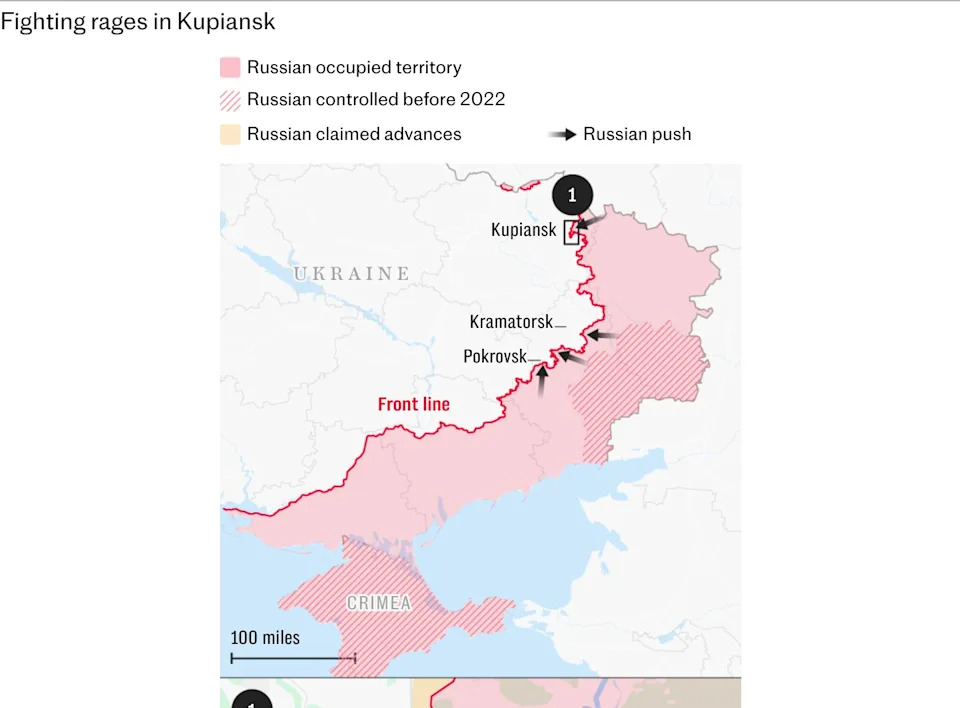

In the North, its forces are creeping back towards the 2022 front line they lost to Ukraine’s blitzkrieg counter-offensive. They have re-entered Kupiansk, the strategic ridge-top town on the Oskil river, and are approaching the Siverskyi Donets river near Lyman. The road between Izyum and Sloviansk is again vulnerable to drone attack for the first time in three years.

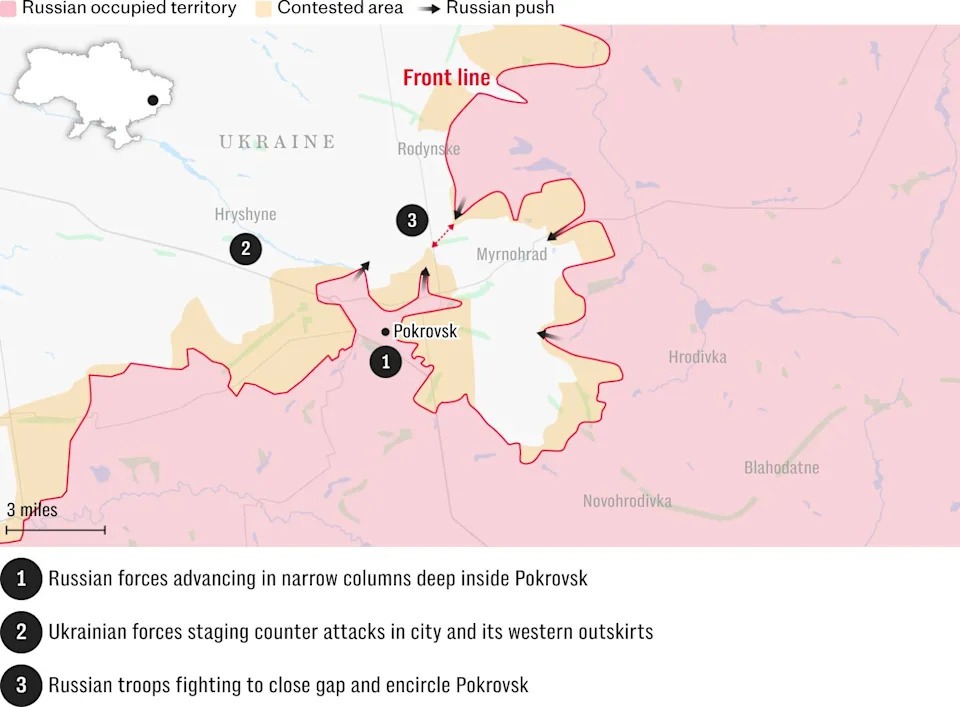

Further south, and after 13 months of effort, the Russians have finally entered and nearly surrounded Pokrovsk. Ukraine’s 38th Marine Brigade, holding out at neighbouring Myrnohrad, will probably have to choose between retreat and encirclement in the coming weeks.

Perhaps most dangerously, Russia has made unexpected progress by effectively turning the flank of the front line in the Zaporizhzhia region. Huliaipole, a strong point that for nearly four years has guarded against a Russian attack from the south, is now being threatened from the east instead.

Those advances are set to continue over winter. Ukraine’s military intelligence agency believes Russia could seize complete control of key towns such as Kupiansk and Pokrovsk around the turn of the year.

b’

‘

No one is in any doubt that such military momentum strengthens Putin’s hand in talks with Washington. Zelensky, he can argue, is in no position to dictate terms.

In theory, winter misery should slow these Russian advances: the cold naturally favours defenders in their warm dugouts, and the infiltration tactics Russia pioneered in Pokrovsk – which require small groups to slip past Ukrainian foxholes and then lie up for days and weeks on end in ditches, basements and ruined buildings – will be potentially suicidal without very serious winter gear.

Overcast skies also make it difficult for reconnaissance drones to operate, which makes it slightly safer to move around and should allow Ukraine to resupply its beleaguered forward positions.

But bad weather works both ways.

On November 14, Russian forces reportedly took advantage of fog – and eastern Ukraine produces very dense winter fogs – to build a pontoon bridge and march nearly five miles to the village of Novopavlivka, south-west of Pokrovsk.

They were noticed too late. Just how many Russians got into the village is unclear; the numbers have been put at between 300 and 500.

b’

‘

Yet the advance on Novopavlivka was not really down to fog. At least, that is the feeling among increasingly vocal critics of Ukrainian strategy.

Some, like the Ukrainian journalist Anna Kalyuzhnaya, insist it was the result of a hollowing out of Ukraine’s infantry, which she in turn attributed to a high-command obsession with counter-attacks.

“Just a year ago the Russians could not even think of this,” she wrote on Facebook of the Novopavlivka incident, along with an appeal to Ukraine’s generals to preserve manpower by adopting a proper defensive stance.

Political activist Serhii Sternenko used his social media platforms to concur. Without a change in strategy, “we are heading towards a strategic-scale catastrophe that could lead to the loss of statehood,” he wrote on X.

“Our defence is falling apart,” he added, and there was a “stunning silence about it”.

A struggle to survive

Worrying as they are, however, the loss of individual towns is a distraction from the real challenge, argues Oleksandr Danylyuk, a former advisor to the defence ministry.

“In terms of a war of attrition, it is not so important if [Russian forces] are exhausting Ukraine in Pokrovsk or Kramatorsk,” he says. “In a war of attrition, the last man standing gets everything he wants.”

This winter, he predicts, will not deliver the Russians the gains they are hoping for. “In terms of achieving any significant collapse of Ukrainian ability to wage this war, the Russians will need two more years if we have the same trajectory,” he says.

“But after those two years, it is a question of the future of Ukraine as a nation, because it is already at half of the [pre-war male fighting-age] population. A significant number of fertile Ukrainian men have been killed. That doesn’t work well for the future of this nation.”

Ukrainians prepare for a difficult winter as dwindling manpower and heavy losses raise fears about the country’s long-term prospects – Maksym Kishka/Frontliner

Danylyuk is among those who believe a fundamental change in the Western and Ukrainian approach to the war is necessary.

First of all, it means abandoning the fantasy that it will just take one more step – be it a cunning battlefield manoeuvre, the arrival of a new weapon, another round of sanctions or a meeting with Trump – suddenly to bring Putin to his senses and end the war.

Instead, he says, Ukraine and its allies should focus on generating more firepower so that fewer Ukrainian troops die and more Russian ones do, forcing the Kremlin to recruit even more troops and possibly contemplate a socially and politically destabilising draft.

And it is not just about killing humans. More Himars and Atacms rockets to destroy high-value equipment like S-300 and S-400 ( surface-to-air missile) air defence systems would eventually erode Russia’s ability to fight a potential future war with Nato.

Taken together, argues Danylyuk, such a strategy would force Moscow to reckon with discontent on the home front, battlefield losses and resultant diplomatic weakness – the very trio of challenges that Ukraine faces now.

In 2025, however, General Winter is wearing a Russian uniform, and it is Zelensky and Ukraine feeling the cold.