Programme co-lead Uwe Morgenstern sampling a spring.

Photo: Supplied / Earth Sciences New Zealand

A world-first study of New Zealand’s aquifers reveals that some wells contain groundwater that is 40,000 years old with scientists warning they’ll be put at risk if too much water is taken.

Earth Sciences New Zealand has developed a series of maps and models identifying the source and flow patterns of our aquifers and large river catchments, as part of a six-year research programme.

It’s found that groundwater provides 40 percent of our drinking water, and has discovered that more than 80 percent of the water flowing through our rivers, streams and wetlands when it’s not raining, is from aquifers.

“That is far, far more than we previously thought and underlines the importance of the inter-connected management of groundwater and surface water if we want to ensure our streams continue,” said Principal Scientist Catherine Moore.

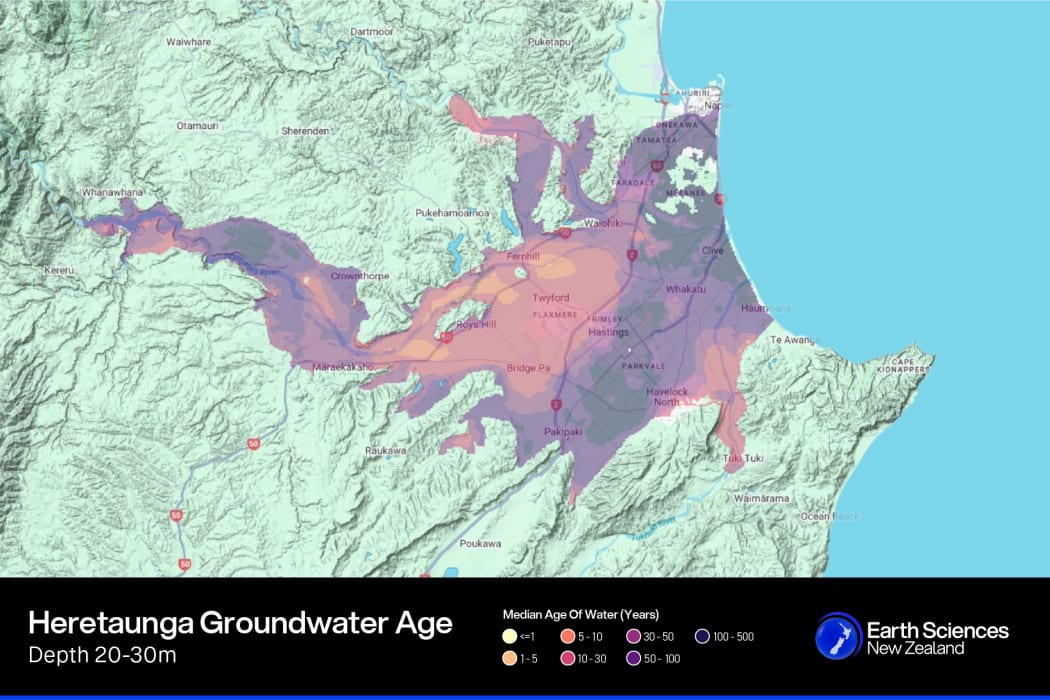

The median age of groundwater in the Heretaunga Plains Aquifer at a depth of 20-30 metres.

Photo: Supplied / Earth Sciences New Zealand

Earth Sciences New Zealand developed the innovative National Groundwater Age Map from more than 1000 groundwater samples to give an overview of groundwater age and groundwater/surface water interaction across the country.

It found that most wells contain water between one and 100 years old.

However, some deep wells in the Taranaki and Marlborough regions hold water that’s over 40,000 years old because it takes so long for surface moisture to seep down into the aquifer.

“The danger is if it takes a long time to replenish we are at risk of taking too much water too quickly. Where water is very old we need to take less water and also look for where water is younger and take water from those areas,” Moore said.

The programme uncovered new insights about connection between groundwater and surface water.

Photo: Supplied / Earth Sciences New Zealand

Areas such as the Wairau, which had the youngest groundwater – taking only two weeks to move through the aquifer system. However the scientists warned that this also presented a challenge as younger systems could be vulnerable to contamination from live pathogens and nitrate loads, whereas older water presented a challenge with nitrate contamination potentially taking decades to work its way through the aquifer.

“Knowledge of water age and flow rates is important for managing potential contamination of drinking water. We’ve created a drinking water protection zone guideline to help protect wells from pathogens in the fast-flowing groundwater found in some of our aquifer systems, such as the Heretaunga Plains,” said programme co-lead and principal scientist Uwe Morgenstern.

The Heretaunga Plains were used as a case study for the modelling, as the Paritua Stream at Bridge Pa in Hawke’s Bay dried up in 2021. Community spokesperson Robert Turner said the stream levels had been declining for years and it’s made it harder for iwi to collect mahinga kai.

“We lost a lot of our kokopu. Eels were stuck in holes. If you look at it in Māori eyes, our river is calling for help,” said Turner.

More than 1000 groundwater samples were analysed to develop the National Groundwater Age Map.

Photo: Supplied / Earth Sciences New Zealand

To understand why it ran dry, the project team gathered historical evidence, including information around the 1931 Napier earthquake, land clearances, gravel extraction, surface water diversions and irrigation.

And what they found was a surprise, as the strongest influence on the flow of Paritua Stream was actually rainfall – not groundwater from the nearby Ngaruroro River as previously thought.

Catherine Moore said that’s given scientists ideas for how to help the stream.

“A wetland restoration engineered a certain way, or directly putting water into the stream, would be sufficient to get that stream to flow if the rate at which that was done was high enough,” she said.

The Te Whakaheke o Te Wai team worked closely with mana whenua in the Heretaunga Plains to understand community concerns about groundwater in the region.

Photo: Supplied / Earth Sciences New Zealand

The newly created National Groundwater Model was expected to cut costs for councils, by giving them quicker access to data that could inform decisions around how much water can safely be taken, and from where.

The interactive map includes data such as geology and soil characteristics, climate, surface water hydrology, groundwater levels, and groundwater age. It can zoom in from national to regional to local scales and can be used to test different scenarios.

“These tools allow decision-makers to build models more cost-effectively, so that they can answer environmental management questions more quickly, wherever they are needed,” said Moore.

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.