Determination of the nasal microbiome in a large cohort

To study the biological basis of S. aureus colonisation in this observational cohort study, samples were taken from the anterior nares from generally healthy human volunteers from the community participating in the CARRIAGE study33 between 13th October 2016 and 17th May 2017 from across England. S. aureus colonisation status was assessed by culture of three self-administered nasal swabs delivered to participants and taken at weekly intervals, and subsequently posted back to the laboratory (Fig. 1a). S. aureus colonisation status was defined as: (i) persistent colonisation, 306/1091 (28.0%), based on three S. aureus culture positive weekly nasal swabs, (ii) intermittent colonisation, 191/1091 (17.5%), defined as one or two swabs positive, and (iii) non-carrier status, 594/1091 (54.4%), defined as no swabs positive, based on previous studies9,10,34,35 (89 failed to return all samples). Lifestyle information was collected by questionnaires or from pre-existing data held as part of baseline questionnaires in previous studies involving the same participants. The Amies transport liquid that the swabs (the same swabs that were used for culture) were transported to the laboratory in were processed without culture for 16S rRNA gene sequencing to identify the microbial community composition (Supplementary Fig. S1 and 2). Participants had a mean age of 51.4 (median, 53) and 52.8% were female. A total of 1756 samples, which included the first swabs of 1180 participants underwent 16S rRNA gene sequencing to determine the microbiome composition (Supplementary Fig. S1). After quality control (QC) (see Methods and Supplementary Table S2), 1055 samples remained, and after rarefaction and a systematic analysis to remove any likely contaminants, 53 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) (24 species level taxa) remained.

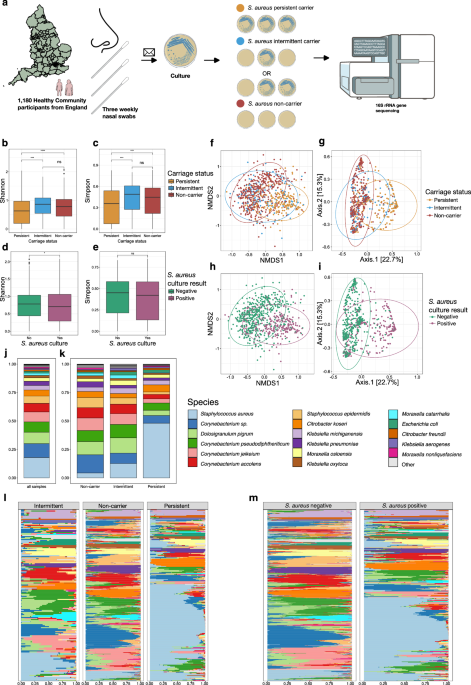

Fig. 1: Study design and nasal diversity and composition by Staphylococcus aureus colonisation status and Staphylococcus aureus culture result.

a illustration of study design and cohort created in BioRender. Ng, D. (2025) https://BioRender.com/r99ahyk. b–e Box plots comparing Alpha diversity (Shannon and Simpson) from nasal samples by (b,c) Staphylococcus aureus colonisation status: persistent (n = 210), intermittent (n = 120), and non-carriers (n = 413) and d, e Staphylococcus aureus culture result: negative (n = 510), positive (n = 284). Each data point is derived from a nasal sample from a distinct individual. The midline of the boxplot represents the median value; the lower limit of the box represents the first quartile (25th percentile), and the upper limit of the box represents the third quartile (75th percentile); the whiskers (upper and lower) extend to the largest and smallest value from the box, no further than 1.5*IQR from the box. Asterisks indicate statistical significance from pairwise comparisons using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (two-sided). Significance levels are denoted as follows: not significant (ns), p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), and p ≤ 0.0001 (****). f–i Ordination plots representing Beta diversity by Bray-Curtis distance and coloured by f, g Staphylococcus aureus colonisation status and h, i Staphylococcus aureus culture result. a–i Staphylococcus aureus colonisation status colours: persistent, orange; intermittent, blue; non-carrier, red. Staphylococcus aureus culture result colours: negative culture, green; positive culture, purple. f, h show NMDS plots g, i show PCoA plots. f, g Bray-Curtis distance between colonisation states significantly differed by one-way PERMANOVA analysis (F(2) = 36.67, p < 0.001). Beta dispersion (PERMDISP) analysis showed significantly greater within-group variability in persistent carriers compared to intermittent carriers and non-carriers (p < 0.001 for both). No difference was observed between intermittent carriers and non-carriers (p = 0.99). Given the ordination plots, the observed differences in beta diversity appear to reflect both shifts in community composition and variation in dispersion. h, i Bray-Curtis distance between Staphylococcus aureus culture positive and negative samples significantly differed by one-way PERMANOVA analysis (F(2) = 59.01, p < 0.001). Beta dispersion (PERMDISP) analysis revealed significantly greater within-group variability among culture-positive individuals (F = 47.2, p = 0.001), suggesting potential heterogeneity in dispersion. Again, the ordination plots showed distinct clustering by group, supporting a shift in community structure rather than an artefact of dispersion. Data ellipses represent the 95% confidence level that values lie within this space, assuming a multivariate t-distribution. j Mean microbial composition of all samples at a species level k Mean microbial composition of samples by S. aureus colonisation status at a species level. l Microbial composition of samples across the study dataset, separated by colonisation status at a species level m Microbial composition of samples across the study dataset, separated by S. aureus nasal swab culture result at a species level. j–m Top 17 species represented. l, m Samples sorted by Bray-Curtis similarity.

Differences in within-sample microbiome diversity

We first investigated variation in Alpha diversity (measures of within-sample diversity) by culture-defined S. aureus colonisation status, to determine differences in the microbiome between S. aureus colonisation states. We found Alpha diversity was significantly lower in samples from persistent carriers when compared to non-carriers or intermittent carriers when using either the Shannon or Simpsons diversity metrics (both p < 0.001), and found no significant difference between non-carriers and intermittent carriers using either (both p > 0.2) (Fig. 1b, c).

We next investigated Beta diversity (similarity or dissimilarity between two samples) (Fig. 1f–i) using Bray-curtis distance by colonisation status, which differed significantly (PERMANOVA analysis, F(2) = 36.67, p < 0.001). Distinct separation of samples from persistent- and non-carriers could be observed by non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) (Fig. 1f) and PCoA (Fig. 1g) ordination plots; Beta dispersion (PERMDISP) analysis showed significantly greater within-group variability in persistent carriers compared to intermittent carriers and non-carriers (p < 0.001 for both) and such variance differences may contribute in part to the PERMANOVA result. However, samples from intermittent carriers did not form a distinct cluster, and instead overlapped within the persistent or the non-carrier clusters, but with more samples from intermittent carriers being clustered with the non-carriers as visualised by the overlap in data ellipses in Fig. 1f, g. This suggests that the microbiomes of intermittent (or rather occasionally S. aureus culture-positive) carriers are not distinct but typically more similar to non-carriers, with smaller numbers that have similar microbiomes to persistent carriers. Likewise, we observed similar distinct clusters between S. aureus culture-positive and culture-negative samples on the ordination plots (Fig. 1h–i). Again, the two groups defined by S. aureus culture result differed significantly by PERMANOVA analysis (F(2) = 59.01, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1h, i). We only observed an association of sex with variation in the Bray-Curtis distance, given females (115/543, 21.2%) are less commonly persistent carriers compared to males (160/511, 31.3%) (p < 0.001), but with a low F statistic and R2 values (F(2) = 2.83, p = 0.006, R2 = 0.39%). There was no association with smoking, pet ownership, healthcare worker, chronic skin condition, and diabetes.

Compositional differences by colonisation status and defining community state types

To visualise the causes of differences observed in Alpha and Beta diversity, we analysed species composition by S. aureus colonisation status (Fig. 1j, k). The lower Alpha diversity of the persistent carriers was associated with the dominance of S. aureus in the species composition of this groups, compared to the intermittent and non-carriers. In contrast, the nasal microbiome of non-carriers is largely dominated by multiple Corynebacterium species and D. pigrum. We next examined species composition at the level of each participant’s sample, separated by colonisation state (Fig. 1l). This showed that amongst the 275 persistently colonised participants, S. aureus was the dominant organism ( > 50% of reads) for 136/275 (49.5%), and in a subset of 96/275 (34.9%) participants, S. aureus represented >75% of reads. In comparison, >50% of reads from S. aureus was only seen in the 22/532 (4.1%), of S. aureus culture-negative (non-carriers) and 26/169 (15.4%) occasionally S. aureus culture-positive individuals (intermittent carriers). Instead, the non-carriers and subset of intermittent carriers were clearly dominated by three different Corynebacterium species (C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. jeikeium, and C. accolens) at abundances not seen in S. aureus persistent carriers (Fig. 1l).

Classifying individual samples by S. aureus culture result revealed that S. aureus was the predominant species ( > 50% of reads) in 164/382 (42.9%) of the S. aureus culture-positive samples, and only 32/672 (4.76%) of culture-negative samples (Fig. 1m). Men are known to have higher S. aureus culture positive rates36,37 and here we found 213/511 (41.7%) swabs returned from male participants were positive for S. aureus on culture compared to 169/543 (31.1%) swabs from female participants. Given our finding that a small proportion of S. aureus culture negative samples have a high S. aureus abundance, we examined the possibility of bias in S. aureus culture by sex; however, we did not find that culture-negative samples with a higher S. aureus abundance ( > 50% of reads) were more prevalent amongst females (17/32, 53.1%) compared to males (15/32, 46.9%). Expectedly, low S. aureus abundance was associated with a S. aureus culture negative result; 92/672 (13.7%) culture negative samples contained no S. aureus reads, whilst 550/672 (81.8%) culture negative samples contained <1% of S. aureus reads (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Community state types

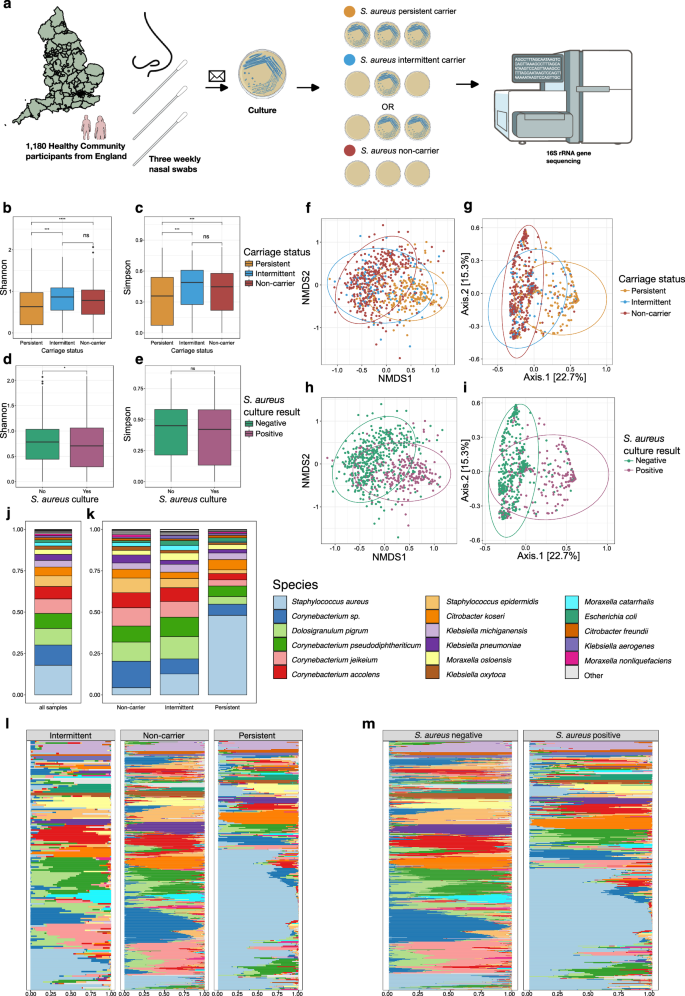

Next, we generated a heatmap of taxa abundance (Fig. 2a), organised by hierarchical clustering by Bray-Curtis distance to examine the relationships between microbial residents of the anterior nares. We used this to define community state types (CSTs), i.e. samples with similar abundances of species which cluster together. To determine the number of clusters in the data, we calculated a gap statistic with ordination values using Bray-Curtis distances (Supplementary Fig. S7). A total of 7 clusters were defined; we identified CSTs from the heatmap plot (Fig. 2a). CST VII, representing a diverse group of sub-clusters is further detailed in Supplementary Fig. S8. From the heatmap, it is evident that individuals always S. aureus culture-positive (persistent carriers) cluster to form the majority of CST I (72.4%, 155/214), whilst those always S. aureus culture-negative (non-carriers) are represented largely by the remaining CSTs (Fig. 2b, c). Intermittent carriers are dispersed across the CSTs. Using a multinomial logistic regression model, we found men had a reduced relative risk for association with CST VI (OR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.30–0.93, p = 0.03) and CST VII (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.47–0.96, p = 0.03) compared with CST I (Fig. 2e). No other significant associations with CSTs were observed. Adjusted odd-ratios are provided in Supplementary Table S5.

Fig. 2: Microbial community state types observed in the anterior nares.

a Heatmap of species abundances in CARRIAGE nasal samples. Samples are ordered by hierarchical clustering using Bray-Curtis distances based on the compositional, relative abundance data, represented by the dendrogram. Prevalence of each species across the samples is represented by the horizontal bar plots. Community state types (CSTs) and S. aureus colonisation status of samples are represented above the heatmap. Seven distinct CSTs were identified from the selection of hierarchical clusters determined by calculating a gap statistic on the Bray-Curtis distance. b Bacterial species dominating each CST. c Composition of CSTs by colonisation status (persistent, orange; intermittent, blue; non-carrier, red). d Composition of S. aureus colonisation status by CSTs. e Composition of each CST by sex. Using a multinomial logistic regression model, we found men had a reduced relative risk for association with CST VI (OR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.30-0.93, p = 0.03) and CST VII (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.47-0.96, p = 0.03) compared with CST I. *significant difference (p < 0.05).

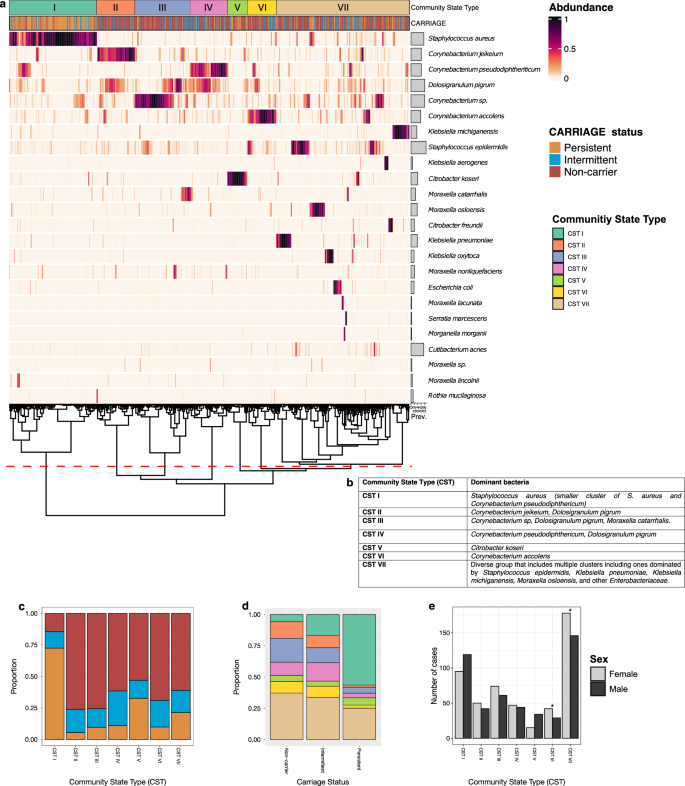

We then formally evaluated differences in species abundances by colonisation status using ANCOM-BC2, which minimises the false discovery rate, using the unadjusted read count table. When comparing always S. aureus culture-negative individuals (non-carriers) and always culture-positive individuals (persistent carriers) carriers, a significant positive association of S. aureus was seen with persistent carriage (as expected), and a significant negative association was seen with multiple Corynebacterium species, D. pigrum, S. epidermidis, and M. catarrhalis (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table S4). No significant differences in species abundance other than S. aureus between non-carriers and intermittent carriers was observed (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table S4). Notably, persistent carriers had a greater log-fold change in S. aureus when compared with occasionally S. aureus positive individuals (intermittent carriers), in comparison to non-carriers, suggesting the relative abundance of S. aureus may be driving its longitudinal carriage.

Fig. 3: Differential abundance, stratified by Staphylococcus aureus carriage status, and co-occurrence network structure of species observed in the anterior nares.

a Differential abundance of species by nasal colonisation status using ANCOM-BC2. Log-fold (natural log) changes as compared to S. aureus non-carriers. Column one compares persistent carriers against non-carriers and column two compares intermittent carriers against non-carriers. b Species-level networks inferred with NetCoMi (v1.2)70 using SparCC correlations (zeroes replaced by a pseudocount; centred log-ratio (CLR) transform; 1000 bootstraps). Network presented with spring layout, plotted with nodes coloured by group and sized by CLR abundance. Species in bold represent the hub taxa for each group.

To further explore the interactions between the different members of the nasal microbiome we generated a co-occurrence network (Fig. 3b). This comprised 24 taxa and 98 edges (density = 0.18; average degree = 8.17; clustering coefficient = 0.43). Several taxa including D. pigrum, S. aureus, and C. pseudodiphtheriticum, exhibited high degree centrality (a measure of how many direct connections each taxon has). The network resolved into four subcommunities (Q = 0.44). Hub taxa identified by eigenvector (EV) centrality (which weights the number of connections and the importance of connected neighbours; Supplementary Table S6) included D. pigrum (Group 1, EV = 1.00), S. aureus (Group 2, EV = 0.79), Citrobacter freundii (Group 3, EV = 0.07), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Group 4, EV = 9.88×10⁻¹⁷). These may represent keystone roles in community organisation.

We next examined the stability of the community in the anterior nares, in a subgroup of 34 participants, from the rarefied dataset to 10,000 reads, two or three samples (n = 75) were available over consecutive weeks (Supplementary Fig. S9–12). These included 13 persistent carriers, 7 intermittent carriers, and 14 non-carriers. We correlated pairwise Alpha diversity of participants (i.e. comparison of diversity indices from samples of the same participant between consecutive weeks) by colonisation status. Persistent (Spearman’s rho = 0.54, p = 0.028) and intermittent carriers (Spearman’s rho = 0.79, p = 0.028) were found to have greater stability compared to non-carriers (Spearman’s rho = 0.30, p = 0.268).

Further examining the microbiome of ‘intermittent’ carriage

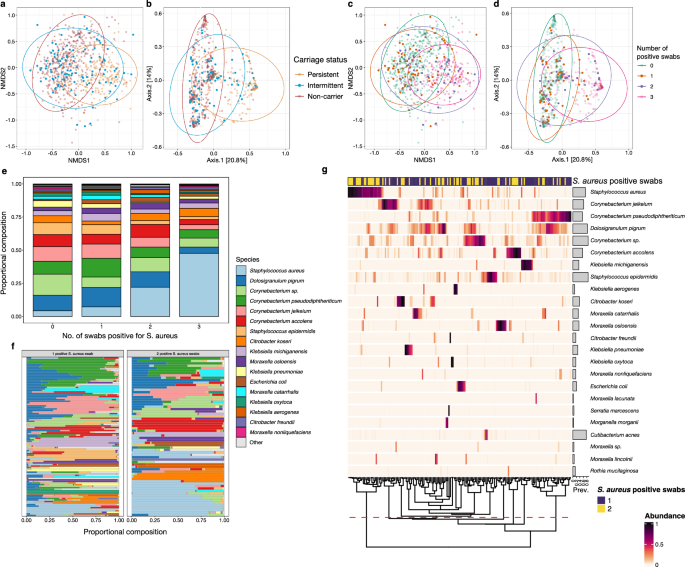

Having observed that the majority of microbiomes of intermittent carriers clustered with those of the S. aureus non-carriers group (e.g. overlapping data ellipses in Fig. 1f, g), we hypothesised that intermittent carriers could be misclassified non- or persistent carriers. We examined differences in Alpha diversity between the one and two swab positive intermittent subgroup (Supplementary Fig. S13), using only samples with greater than 10,000 reads. We found no significant difference in Alpha diversity when comparing samples with one S. aureus positive swab compared with two (p = 0.21). Beta diversity by Bray-Curtis index between samples with one or two positive S. aureus swabs did differ significantly by PERMANOVA analysis (F(2) = 3.19, p = 0.003), suggesting that these groups have differing microbial compositions (Fig. 4a–d).

Fig. 4: Microbial composition of species in the anterior nares by the number of positive S. aureus swabs, with a focus on intermittent carriers.

a–d Ordination plots representing Beta diversity by Bray-Curtis distance and coloured by Staphylococcus aureus colonisation status and the number of S. aureus culture-positive swabs relating to each participant represented. a, c show NMDS plots b, d show PCoA plots. a, b Fig. 1 panels f to g have been reproduced to highlight the distribution of intermittent carriers (blue) and with S. aureus non-carriers (red) and persistent carriers (blue) faded into the background. The values representing intermittent carriers on the ordination plots of Bray-Curtis distance visibly span both the non-carrier and persistent carrier clusters. c, d These plots represent the same Bray-Curtis distances as shown on panel a to b but with points coloured by the number of positive swabs from the participant. Despite limited numbers, it is apparent that there is greater overlap of the non-carriers (0 positive swabs, green) with the participants with 1 positive swab individuals (orange), and a similar relationship is seen between the participants with 2 positive swabs (purple) and the persistent carriers (3 positive swabs, pink). e Mean abundance by the number of swabs positive for S. aureus including non-, intermittent and persistent carriers. f Microbial composition represented by relative abundance of species residing in the anterior nares of individual intermittent carriers, comparing the number of Staphylococcus aureus culture positive swabs obtained (one vs two). g Microbial composition of the anterior nares from intermittent carriers represented as a heatmap. The number of samples positive for S. aureus (1, purple; 2, yellow) from the participant associated with the represented participant sample is shown in the bar above the heatmap. Samples are ordered by hierarchical clustering using Bray-Curtis distances on the compositional relative abundance data. Prevalence of each species is highlighted in the horizontal bar plots. The dashed red line represents splitting of hierarchical clustering dendrogram in seven community state types, as determined by the gap statistic. Participants with two positive swabs appear to have a higher abundance of S. aureus.

We next explored the abundance of species across the samples depending on the number of swabs which were positive for S. aureus. There is a clear continuous trend in the variation in abundance from zero to three positive swabs (Fig. 4e). We then subset the participants representing intermittent carriers (n = 169) from the dataset to examine if these were two distinct populations (rather than one) based on the number of S. aureus positive swabs (one swab, n = 103 and two swabs, n = 66). From examination of the species composition of individual samples, a different microbial community structure is apparent for intermittent carriers who are positive for two swabs compared to those with one swab (Fig. 4f).

We formally analysed the differences in community structure using a heatmap of abundances from the samples of intermittent carriers, which displays a similar structure of clustering to that observed when comparing persistent carriers (Fig. 4g). Again, we calculated a gap statistic, giving an optimal number of CSTs of 7 (same as full dataset), and the hierarchical clustered dendrogram was split accordingly (Fig. 4g). On this heatmap, it is clear that the CSTs that are dominated by Corynebacterium species, D. pigrum and S. epidermidis are associated with samples where participants had one positive S. aureus culture. 18/66 (27.3%) intermittent carriers who had two positive S. aureus cultures were associated with a CST dominated by S. aureus, compared to 7/103 (6.8%) with one positive swab. These findings reflect similar observations for persistent carriers and non-carriers, respectively (Fig. 1F, G), and provide further evidence that, with respect to the underlying microbiome, intermittent carriers do not possess a distinct phenotype and are either similar to persistent carriers or non-carriers.

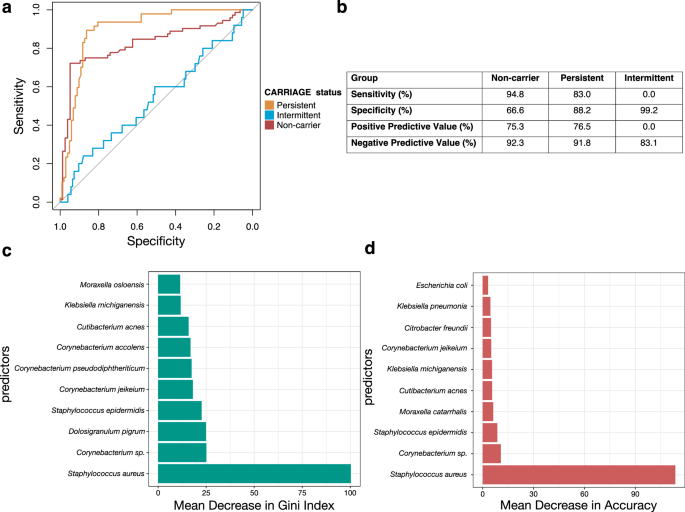

Predicting colonisation status from the nasal microbiome

We next used a random forest model to establish whether microbiome data could be used to predict the culture-based categorisation of nasal S. aureus colonisation status. Additionally, this served as a sensitivity analysis for the previous differential abundance analysis (Fig. 3A), which allows for the identification of significant microbial determinants for S. aureus colonisation status. We split the data into training and test data at a ratio of 80:20, and determined the best number of candidates to be sampled at each tree (mtry) to be 6. The estimated test classification accuracy of the trained model was 73.2% (1-estimated out of box error) with the lowest class error for non-carriers (6.85%) and highest for intermittent carriers (100%).

We determined the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the model with the test data. The overall accuracy of the model was 75.2% (95% CI = 67.4%-81.9%, p < 0.001) significantly exceeding the no information rate (Fig. 5A). Overall, the model performed best in predicting persistent colonisation with 83.0% and 88.2% sensitivity and specificity, respectively, suggesting the greatest utility for identification of individuals at higher risk of persistent S. aureus colonisation (Fig. 5B). For non-carriers, the sensitivity was higher at 94.8%, but specificity lower at 66.6%. For intermittent carriers the sensitivity was 0.0% suggesting the model was completely unable to predict the intermittent colonisation from the microbiome data; of the 25 intermittent carriers in the test dataset, none were classified as intermittent carriers, 16/25 (64%) were misclassified as non-carriers and 9/25 (36%) as persistent carriers, adding further evidence that intermittent carriers are not distinct group, and a greater proportion are similar to non-carriers compared to persistent carriers.

Fig. 5: Random forest classifier of the nasal microbiome data.

a ROC curves demonstrating model performance for classification of non-carriers vs others (grey line), persistent carriers vs others (blue line), and intermittent carriers vs others (red line). The multi-class area under the curve was calculated as 76.8%. b Performance of the random forest model to predict the nasal microbiome. Values provided as percentages. c Feature importance as determined by mean decrease in gini index from the random forest classifier. d Feature importance as determined by mean decrease in model accuracy from the random forest classifier.

We determined variable importance (i.e. how much each variable contributes to the prediction) by evaluating the mean decrease in accuracy (a measure of decrease in the model accuracy computed by permuting out-of-box error data) and the mean decrease in gini index (a measure of variance and resulting misclassification across the random forest nodes) after removal of each feature, i.e. taxon38. The top three features of importance by assessing the mean decrease in accuracy were S. aureus, Corynebacterium sp., and S. epidermidis (Fig. 5c). The top three features of importance by assessing the mean decrease in gini index were S. aureus, Corynebacterium sp., and D. pigrum, with S. aureus clearly contributing the most to the model (Fig. 5d).

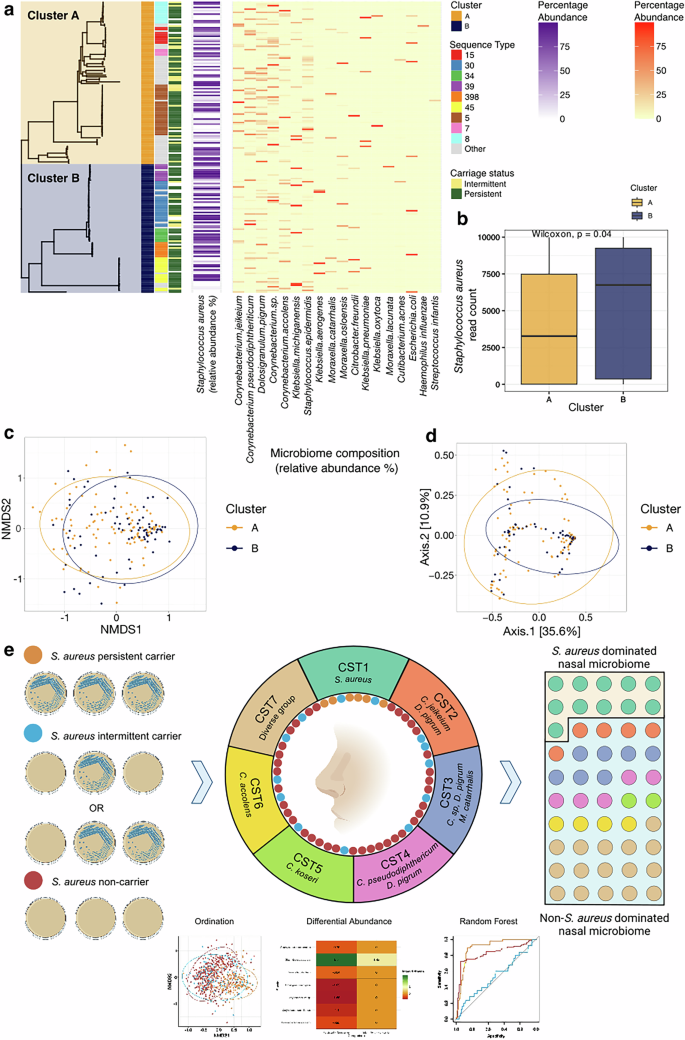

Staphylococcus aureus phylogenetic associations with carriage

We next investigated if certain S. aureus lineages have a propensity for persistent nasal carriage or are more capable of dominance of the community compared to other competing resident bacteria. We used S. aureus isolate whole genome sequences with matched microbiome data (n = 172) and compared the S. aureus phylogenetic tree, and major multi-locus sequence types (MLST), to the colonisation state and the sample microbiome (Fig. 6a). Two clusters are defined at the bifurcation at the root of the phylogeny (Cluster A and B, Fig. 6a), as seen in large collections of diverse S. aureus39. There is a greater number of samples showing higher S. aureus abundance amongst isolates in cluster B (dominated by ST30, ST34, ST398, and ST45) with a lower number of samples showing higher abundance of species identified earlier as showing a negative association with S. aureus (Fig. 3a) than in Cluster A (dominated by ST5, ST8, ST15, ST7, and others). Matched CST data was available for 125 samples; 38/74 (51.4%) of cluster A compared to 33/51 (64.7%) cluster B samples were found in the S. aureus dominant CST I (Fig. 2). We examined differences in rarefied (i.e. per-sample normalised read data) S. aureus abundance (n = 111), which demonstrated a significantly higher abundance in samples in cluster B compared to cluster A (Mann-Whitney, p = 0.04) (Fig. 6b). Next, we assessed differences in Beta diversity between cluster A and B (Fig. 6c, d), and found a small but statistically significant (PERMANOVA analysis (F(2) = 2.33, p = 0.04) divergence of these groups. This suggests that S. aureus abundance and the associated microbiome (when S. aureus is present) is to some degree lineage specific.

Fig. 6: Variation of the anterior nares microbiome with the Staphylococcus aureus phylogeny.

a Maximum-likelihood tree of S. aureus whole-genome sequences cultured from persistent and intermittent carriers labelled with their associated carriage status, sequence-type and microbiome. b Box plots comparing rarified S. aureus abundance by cluster: cluster A, n = 62; cluster B, n = 49. Each data point is derived from a nasal sample from a distinct individual. The midline of the boxplot represents the median value; the lower limit of the box represents the first quartile (25th percentile), and the upper limit of the box represents the third quartile (75th percentile); the whiskers (upper and lower) extend to the largest and smallest value from the box, no further than 1.5*IQR from the box. Statistical significance from pairwise comparisons tested using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (two-sided), (p = 0.04). c, d Ordination plots representing Beta diversity by Bray-Curtis distance and coloured by the phylogenetic clusters (A or B) representing the bifurcation of the tree. Bray-Curtis distance between samples representing phylogenetic clusters A and B samples significantly differed, although weakly, by PERMANOVA analysis (F(2) = 2.33, p = 0.04). Beta dispersion (PERMDISP) analysis showed no significant difference in dispersion between groups (F = 1.26, p = 0.29). c shows an NMDS plot d shows a PCoA plot. Data ellipses represent the 95% confidence level that values lie within this space assuming a multivariate t-distribution. e Graphical representation of abstract created in BioRender. Ng, D. (2025) https://BioRender.com/o73y544.