As 2025 wraps up an eventful year in foreign policy, five CFR fellows look ahead to what they’ll be watching in 2026. In charts, graphics, and maps, our experts consider how the United States will navigate the growing need for critical minerals, whether tariffs will dig deeper into U.S. consumers’ pockets, if the last remaining nuclear agreement between Washington and Moscow can be saved, the ways China’s electrification surge could popularize the emerging “electrostate,” and why women will be the most affected by humanitarian aid cuts.

The Accelerating Race for Critical Minerals

More From Our Experts

Heidi Crebo-Rediker is a senior fellow in the Center for Geoeconomic Studies.

More on:

In 2025, the U.S. Department of Energy labeled sixty minerals as “critical” due to their importance in defense -industrial sectors at home and vulnerability to supply shocks abroad. As economies and militaries increasingly rely on digital communications systems and renewable energy sources, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that global demand for critical minerals could nearly triple by 2030.

Yet by that same year, the IEA estimates the United States will hold less than 2 percent of the world’s critical minerals market compared to China’s 31 percent. With applications ranging as widely as smartphones, electric vehicle batteries, F-35 fighter-jet engines, and brain imaging equipment, the need for a secure, stable source of critical minerals will continue to drive geopolitical competition and define U.S. foreign policy in the year ahead.

The critical minerals supply chain is highly concentrated, creating dependencies and risking shortages for U.S. buyers as countries threaten to restrict exports and leverage their pricing power to preempt competition. The Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, is home to 62 percent of the world’s cobalt supply. When it comes to global processing, China controls up to 90 percent, the most consolidated pillar of the supply chain. Together, these bottlenecks have made the United States heavily reliant on imports—completely dependent for twelve critical minerals and more than 50 percent import-dependent for twenty-eight additional minerals.

More From Our Experts

The World This Week

CFR President Mike Froman analyzes the most important foreign policy story of the week. Plus, get the latest news and insights from the Council’s experts. Every Friday

Building on efforts initiated during the first Trump administration and expanded under President Biden, the second Trump presidency has pursued two sets of policies to reduce Washington’s critical minerals vulnerability.

First, following a series of executive orders early in the Trump administration, the Commerce Department, Defense Department, and a number of agencies, including EXIM and the DFC, embarked on a muscular industrial policy to invest in U.S. mineral resilience through domestic and allied public investments. These investments included a range of loans and loan guarantees, quasi-equity and equity, price floors and purchase agreements.

Second, the White House struck several bilateral and multilateral agreements to gain access to diversified foreign mineral supplies, coordinate financing to scale production, and align legal codes and industry standards. These measures include the Critical Minerals Action Plan signed at the Group of Seven (G7) Summit in June, the Quad Critical Minerals Initiative pledged in July, and over $10 billion in announcements to jointly finance, build, and stockpile critical minerals supplies with Asian countries in October.

More on:

These two lines of effort to secure critical minerals supply-chains will continue to drive the Trump administration’s diplomacy and industrial policy in 2026. In a year that will also see shifting regional security architectures and sustained geopolitical rivalries, the pace, durability, and direction of U.S. progress on critical minerals supply chain security is much less certain.

More Tariff Costs to Consumers

Benn Steil is senior fellow and director of international economics.

As we move into 2026, a major unknown for the global economy is how President Trump’s tariff policies will evolve and what effects they will have. Questions loom over whether the Supreme Court will shoot down his so-called reciprocal tariffs, if trade deals will subsequently be rejigged, or if the public’s concern with affordability—and industry’s concern with competitiveness—will lead to a mass of exemptions.

An important ongoing but much-disputed question is who actually pays the president’s tariffs. While in practice, tariffs are taxes paid by U.S. importers, importers can pressure foreign exporters to cut their prices, shifting part of the burden abroad, or they can pass on the cost to American consumers through higher prices.

In June, three months after Trump’s April 2 “Liberation Day” tariff bombshell, U.S. importers bore most of the tariff burden at 64 percent, according to Goldman Sachs economists. In the early months after “Liberation Day,” importers were unable to shift to lower cost suppliers and thus had minimal leverage to compel existing foreign ones to reduce prices. Additionally, importers refrained from raising consumer prices, having built up inventory and believing—or hoping—that tariffs were merely a negotiating tool. Foreign exporters bore only 14 percent of total tariff costs in the form of lower import prices, while U.S. consumers took on 22 percent in the form of higher retail prices.

But the picture had changed considerably by October. Importers then bore only 27 percent of the tariff burden—less than half the June estimate. Exporters undertook a slightly higher 18 percent, and consumers suffered a much higher 55 percent—consistent with the slowly rising inflation data. This shift took place as importers sought out alternative suppliers, giving them a bit more negotiating leverage. The administration had also announced several bilateral trade deals, or “framework” deals, which made clear that substantial tariffs were here to stay. That is, they were not going back down to Biden-era levels. This gave importers and retailers good reason to pass on more of the costs to consumers.

What that picture will look like next year still depends on what tariffs go up or down, and what tariffs are added or waived. But given the baseline assumption of little change, the data suggests that importers will, at mid-year, bear only about 8 percent of the tariff burden. By this time, they will have had far greater opportunity to seek out lower-cost alternative suppliers. The exporter burden should therefore rise to about 25 percent. The consumer share, meanwhile, is expected to climb to 67 percent.

In the end, U.S. consumers will wind up shouldering most of Trump’s tariffs, sending the inflation contribution of tariffs up as well. In the best case, consumers pull back on spending just enough to keep prices in check, but not enough to push the economy into recession. The worst case is “stagflation”—a combination of higher inflation and recession. The good news is that such a disaster would be wholly man-made, and can therefore be un-made by slashing tariffs that don’t, in fact, aid national security or competitiveness.

The End of Arms Control

Erin D. Dumbacher is the Stanton nuclear security senior fellow.

In February, the last remaining arms control treaty on limiting nuclear weapons between the United States and Russia is set to expire. The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) bilateral agreement aims to maintain strategic stability and avoid a renewed arms race. With enough nuclear weapons to hold each other at risk already, the logic goes, the two countries could each meet their national security aims with less than 1,550 deployed nuclear weapons.

The treaty also encompassed rigorous verification methods to assure to each side that the other was complying. New START established detailed limits on deployed strategic delivery systems and included robust verification provisions, including on-site inspections and protections for each side’s use of national technical means to monitor compliance.

In 2026, the United States and Russia will hold 87 percent of the world’s nuclear bombs and warheads. With the end of New START in sight, the United States and Russia face futures with no legally binding restrictions on their nuclear arsenals, and no requirements for transparency. Other past treaties, such as Open Skies, Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces, and Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, have ceased to be in effect. Only the Non-Proliferation Treaty will impose legally binding constraints: under its terms both the United States and Russia are recognized nuclear weapons states without limits on their deployed weapons, although each party is required to pursue negotiations “in good faith” on “cessation of the nuclear arms… disarmament.”

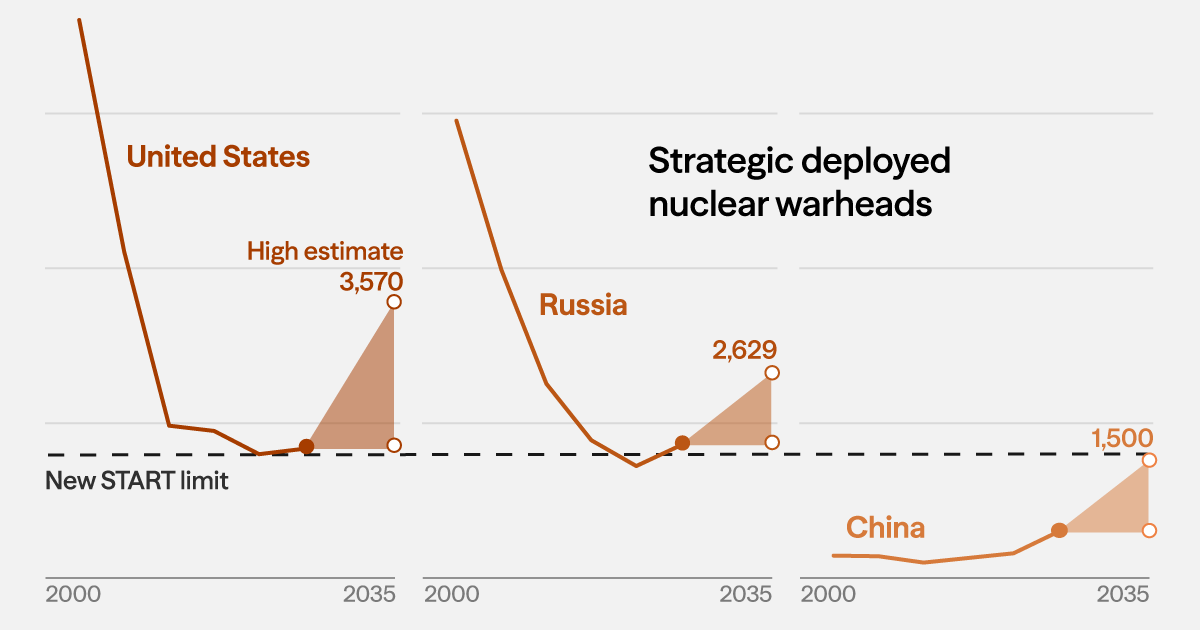

Without the constraints of New START, the United States and Russia might opt to take nuclear weapons out of their stockpiles and deploy them for prompt use. According to the Federation of American Scientists, it is possible that following the end of New START, the number of deployed warheads between the United States and Russia will top six thousand within a decade. China itself is on track to have as many as 1,500 warheads by 2035. Any additional deployments of nuclear weapons from the United States or Russia could encourage states like China to continue enhancing their own forces, making nuclear use more likely and increasing the risk of nuclear accidents. Looking into 2026, the end of controls on nuclear arms around the world seems likely.

The Rise of the ‘Electrostate’

David M. Hart is a senior fellow for climate and energy.

A new buzzword appeared this year in the global energy and climate policy lexicon: “electrostate.” The term contrasts with “petrostate,” and its archetype is China.

One meaning of the term rests on the share of electricity in a nation’s final energy consumption. High-income countries tend to use more electricity because the sectors that consume fuels directly—including agriculture, mining, and manufacturing—are a smaller slice of their economies, while the service sector, which relies primarily on electricity, is larger. By this logic, China, a middle-income country, should lag behind the United States and the European Union, but it has recently surpassed both.

China is breaking the mold in part because it is rapidly electrifying transportation. More than 50 percent of passenger vehicles sold in 2025 were propelled by electricity. That figure will hit 73 percent in 2030. Buses and motorcycles are already further down this curve, and even trucks have begun to follow it.

To support this surge in electrification, China has expanded and improved its power grid. As recently as fifteen years ago, the country suffered from power shortages. Its grid operators then embarked on a massive effort to build 60,000 kilometers of ultra-high-voltage transmission lines by the end of 2023. This growth enabled the extraordinary boom in renewable generation, which now provides more than a quarter of China’s electricity, twice the share from just three years ago.

China’s solar industry highlights a second meaning of electrostate: one that exports energy resources. Solar panels, electric vehicles (EV), and batteries comprise the “new trio” driving China’s exports. Beijing dominates global trade in solar panels and the entire supply chain that feeds into them. Cheap Chinese panels are enabling developing nations like Brazil, Pakistan, and South Africa to reduce their reliance on imported fuels, and low-cost EV and battery exports are furthering this trend. (Indeed, the price of solar panels has dropped so quickly that the decline in export value pictured below masks continuing growth in exported panels’ generating capacity.)

These exports raise the question of whether energy importers are simply replacing dependence on petrostates like Saudi Arabia with dependence on the emerging Chinese electrostate. This argument has some validity, but there’s a huge distinction: a disruption in fuel supplies has an immediate and potentially catastrophic effect on economic activity, while a disruption in solar or battery imports affects only future electric capacity. The latter is far more appealing for many countries who now have a choice between the two.

The Chinese electrostate has profound momentum, and it is spilling over the rest of the world. “The Age of Electricity,” the International Energy Agency concluded in its recent World Energy Outlook report, “is here.” While the petrostate may not yet be in the rearview mirror, the electrostate has begun to pass it by. As science fiction author William Gibson famously said: “The future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed.” You can find this part of the future in China today.

Women Bear the Brunt of U.S. Foreign Aid Cuts

Linda Robinson is senior fellow for women and foreign policy.

The Donald Trump administration has slashed the United States’ foreign aid this year, throwing the international aid delivery system into chaos at a time of record conflicts.

Historically, the United States has represented over half of global official development assistance (ODA), providing over $63.3 billion in 2024. For fiscal year 2025, enacted foreign aid dropped to $38.4 billion, with additional rescissions cutting this number by at least $9.4 billion. Funding for 2026 stands at $28.5 billion, with estimates as low as $8.1 billion, including rescissions and cancellations. There have been more than 350,000 deaths attributed to aid cuts since January, when Trump signed an executive order freezing foreign aid.

As a result of the administration’s cuts, millions of women and girls are disproportionately suffering and face direct threats to their health and security. Bearing the brunt of war, women and girls rely on humanitarian aid for survival. The United Nations estimates that 676 million women live in conflict zones, where instability increases conflict-related sexual violence and food and economic insecurity. Millions more displaced and refugee women are more likely to experience violence and abuse, including child marriage, rape, sexual and labor exploitation, and trafficking. In Sudan, for example, nearly eleven million women and girls are food insecure, and women in remote and besieged areas risk sexual violence and abduction. And in Afghanistan, women lack the ability to work or travel, and more than two-thirds of women-led households are forced to marry their daughters off for survival.

Nearly 224 million women globally lack access to family planning methods and are reliant on aid to access health care, including sexual and reproductive health resources. Funding cuts have cut over 90 percent of all maternal, child, and reproductive health care assistance provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and, earlier this year, the State Department destroyed $9.7 million worth of contraceptives for women in low-income countries. Estimates show that if U.S. funding is not renewed at the level of fiscal year 2024, millions of women will be denied contraceptives, resulting in more than seventeen million unintended pregnancies, and more than thirty-four thousand pregnancy-related deaths.

Development aid and humanitarian assistance have been hit the hardest. The Trump administration provided small amounts of disaster relief in March following devastating earthquakes in Myanmar [PDF] and have sponsored some public health assistance to the Philippines and emergency food aid—but rescinded $5 billion in other aid in August. Except for some critical health funding, including President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) aid for HIV treatments, U.S. development aid has been largely eliminated, and USAID has been shuttered. The repercussions are being compounded as other countries have followed suit. In addition to the United States, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom have reduced their aid this year, for the second year in a row. A recent study estimated that U.S. and European aid cuts could cost an additional 22.6 million lives by 2030 if the trend is not reversed. While budgetary talks are still underway, there is little sign that 2026 will see a comeback in foreign aid.

This work represents the views and opinions solely of the authors. The Council on Foreign Relations is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher, and takes no institutional positions on matters of policy.

Mariel Ferragamo edited this article. Austin Steinhart created the graphics. A.J. Dilts, Noël James, and Gabriela Reitz contributed.