As the flames of the Palisades fire licked at his home, Ricardo Kawamura stood in his front yard watching smoke pour out of a second-story window. He saw a fire engine parked next to a hydrant on his street, and called for help.

“They told me they did not have enough water,” Kawamura said. “And unfortunately, there was nothing that they could do at that time.”

After two of the most destructive fires in the state’s history, The Times takes a critical look at the past year and the steps taken — or not taken — to prevent this from happening again in all future fires.

As the fire spread, the water system quickly lost pressure as crews drew heavily on hydrants, residents ran sprinklers and hoses, and water gushed out of melted pipes. Hillside tanks ran out of water, and many hydrants, particularly in higher-elevation areas, lost pressure and ran dry.

An additional source of frustration for residents was the fact that one vital water asset — the Santa Ynez Reservoir — sat empty and dry as their neighborhoods burned.

How did entire communities find themselves in the midst of raging fires without enough water on hand to fight them?

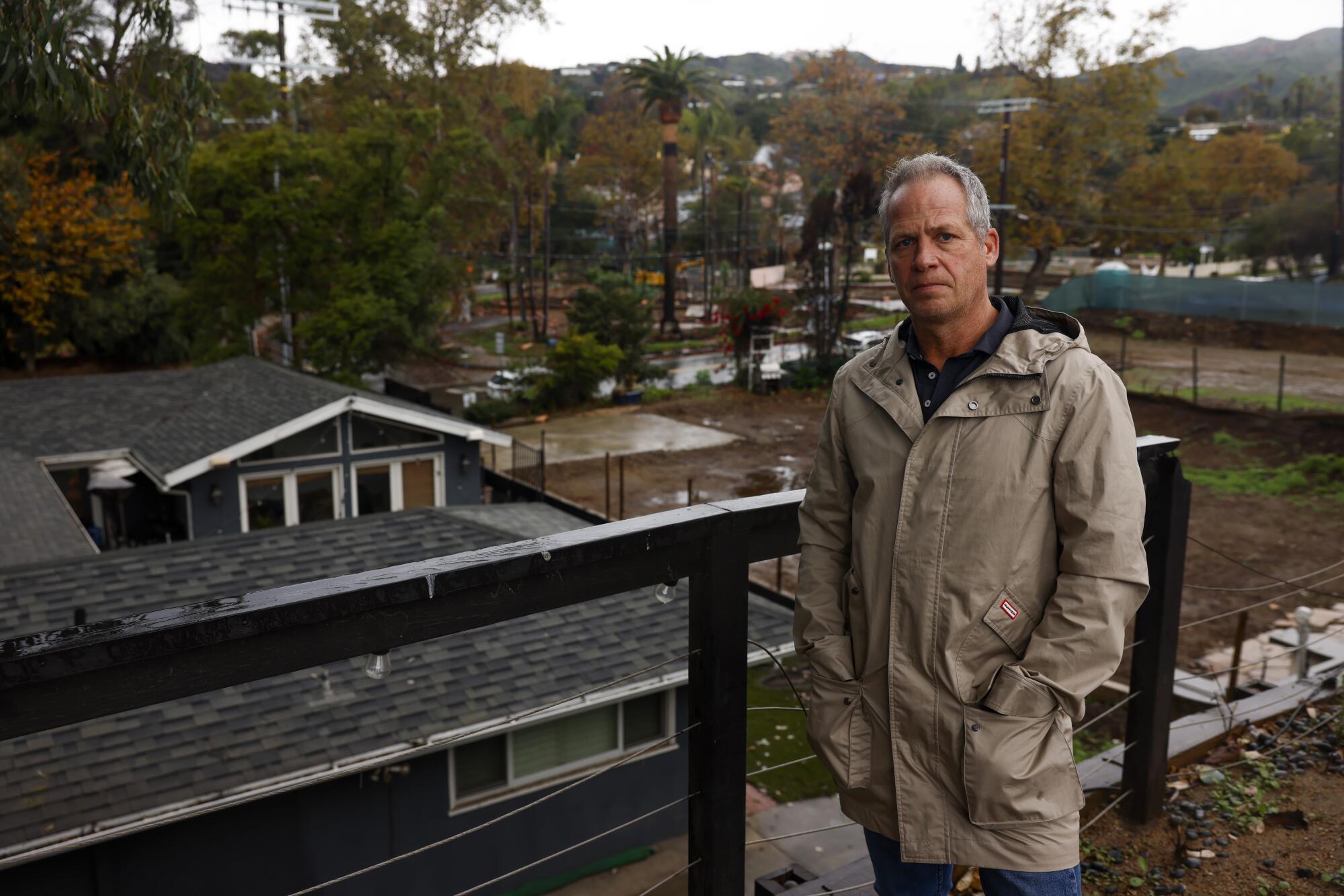

Ricardo Kawamura stands in a home he is building in Pacific Palisades. The house was under construction when the fire hit. He defended it using a garden hose, and with help from firefighters. “Water was key,” he says. “Houses that had access to water are still standing.”

The answers have exposed the weaknesses of Los Angeles’ water systems and prompted widespread calls to redesign Southern California’s water infrastructure. Water managers and experts said the water systems in Pacific Palisades and Altadena were never designed for wildfires that rage through entire neighborhoods, or for infernos intensified by climate change. In fact, their design effectively guaranteed that hydrants would lose pressure and fail during a giant fire.

The loss of pressure in hydrants had happened before in various wildfires, including the 2008 Freeway Complex fire, the 2017 Tubbs and Thomas fires, the 2018 Woolsey fire and the 2024 Mountain fire.

But the historic devastation of the Palisades and Eaton fires has led residents and experts to search urgently for ways to ensure more water is available next time.

Ricardo Kawamura stands on the driveway of his family’s rental home, which burned down in the Palisades fire. There is a hydrant across the street, but a firefighter told him they didn’t have enough water. “We feel let down,” he says.

Proposed ideas include installing emergency shutoff valves that can reduce the loss of water as buildings burn, designing new neighborhood systems with cisterns that store water for firefighting, encouraging the use of household firefighting equipment that draws on swimming pools, and having temporary pipes and pumps that can be deployed quickly when a fire erupts.

So far, however, local officials in Los Angeles and L.A. County appear to have taken few, if any, concrete steps toward major changes.

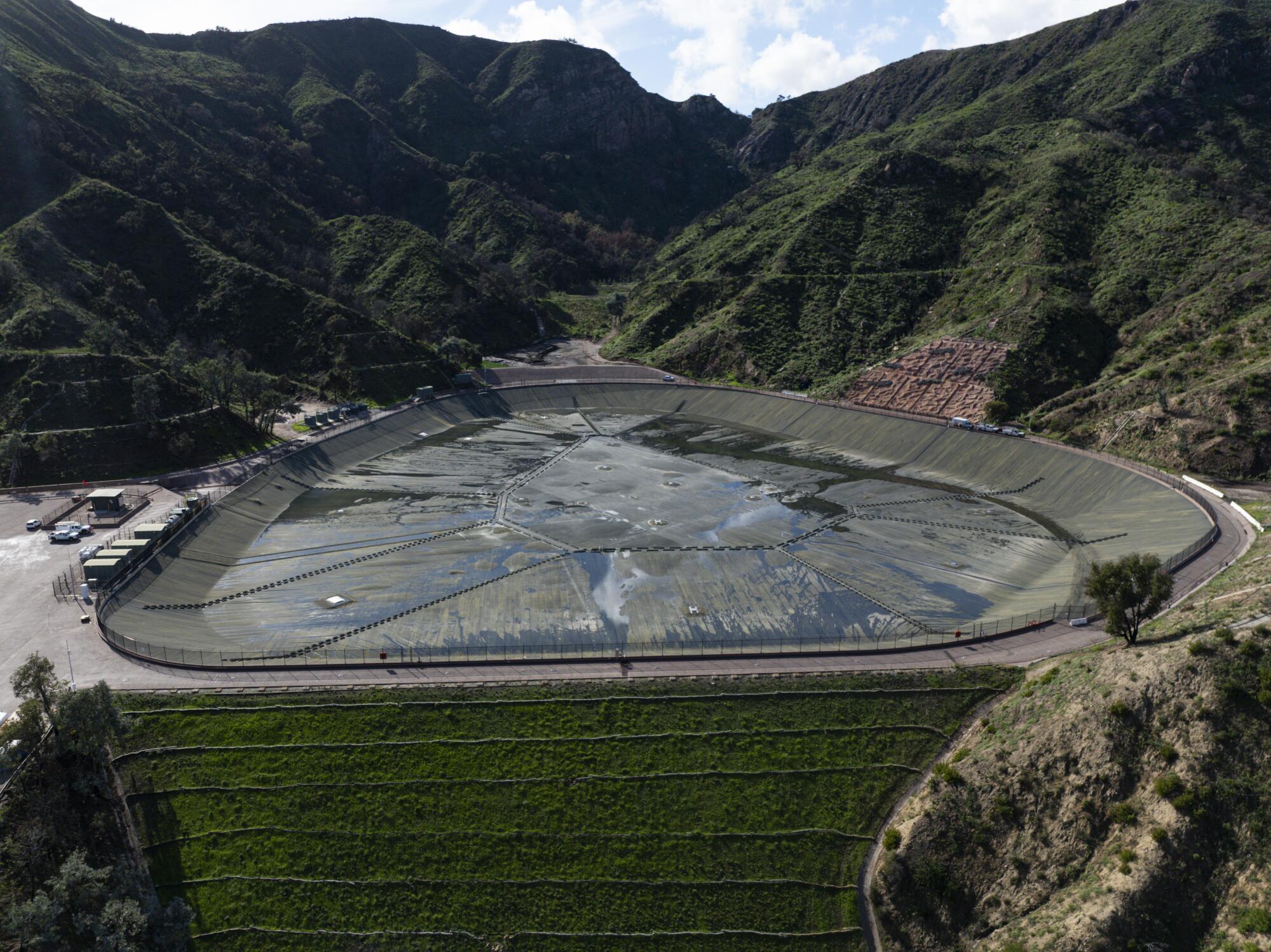

When the flames began tearing through Pacific Palisades, the 117-million-gallon Santa Ynez Reservoir had been empty for nearly a year. In early 2024, a major tear was discovered in its floating cover. The contractor hired to do the repairs had not yet begun when the fire exploded.

Having this key piece of the water system empty at a time of high fire danger was inexcusable, said George Engel, an entertainment executive whose house was left standing while neighboring homes were destroyed.

“The city wasn’t prepared for it at all,” Engel said. “We just basically had no support.”

George Engel stands next to his Pacific Palisades home, which was damaged but remained standing after the Palisades fire.

The Palisades fire killed 12 people and destroyed thousands of homes.

“This should never happen again,” Engel said. “We need to learn from this. We need to fix it.”

After a 10-month review, California officials concluded that it had been necessary to drain the reservoir to protect public health, and that even if the reservoir had been full, the system of pipes throughout the area “would have been quickly overwhelmed” and lost pressure because of its limited flow capacity.

The L.A. Department of Water and Power has defended how the water system performed, saying hydrants lost pressure because of extraordinary demand.

“The water issues during the fire were not a result of a lack of water supply but rather a loss of pressure issue due to thousands of leaks and depressurization as a result of the fire damage and firefighting efforts,” Ellen Cheng, a DWP spokesperson, said in a written statement. “Municipal water systems are not built to extinguish large scale wildfires which are usually fought by air.”

Some experts, though, agree with residents that having the reservoir out of commission was a problem.

The covered Santa Ynez Reservoir in Pacific Palisades in November 2025.

“If we know there hasn’t been rain for eight months, [it’s] not a good time to be doing large-scale maintenance projects that are going to keep any part of your water system offline,” said Mark Gold, a member of a commission created to examine solutions for climate-resilient rebuilding.

DWP is now facing lawsuits filed by homeowners, who argue the utility failed to adequately prepare for the fire. Some residents have erected yard signs calling for the resignation of L.A. Mayor Karen Bass.

Responding to a question about the lengthy repairs at the reservoir, Cheng said that the agency has since “made several key leadership changes as part of an ongoing effort to improve procurement operations,” including appointing a new head of water operations and a new administrative officer who oversees procurement of goods and services. She did not elaborate on the changes.

Where a home was destroyed in the Palisades fire, a new house is being built in Pacific Palisades.

Gregory Pierce, co-director of UCLA’s Luskin Center for Innovation, said large wildfires intensified by climate change are making the limitations of water systems more visible. In a recent article, Pierce and other researchers wrote that California’s urban drinking water systems are built to “fight smaller-scale urban structural fires” but are not “designed to fight large wildfires” and that no water system could have stopped such intense fires.

Crews also encountered failing hydrants in Altadena as they battled the Eaton fire. UCLA researchers have found that hydrants similarly lost pressure during many other major fires over the last decade.

Pierce and other researchers say efforts to improve firefighting capacity could include investing in new infrastructure, lining up dedicated supplies for firefighting and creating backup power to keep pumps running if there are outages.

In a June report, the Blue Ribbon Commission on Climate Action and Fire-Safe Recovery outlined various proposals for maintaining water pressure during fires, saying it will require a “coordinated regional approach, collaboration across agencies, and flexible access to alternative sources” of water.

Tapping into home water resources

The independent 20-member Blue Ribbon Commission on Climate Action and Fire-Safe Recovery recently recommended that L.A. city and county governments adopt new standards for household firefighting systems. Some examples:

External sprinklers that draw from cistern, pool or other water source via a pump.

Solar or battery-operated pumps that draw from cistern, pool or other water source.

Rainwater

collection tanks

Pipe connection lines from water supply to the street that provide firefighters with quick access.

Water to fight fires from a pool or from rainwater stored in tanks or a cistern.

A) External sprinklers that draw from cistern, pool or other water source via a pump.

B) Solar or battery-

operated pumps that draw from cistern, pool or other water source.

Rainwater

collection tanks

C) Pipe connection lines from water supply to the street that provide firefighters with quick access.

D) Water to fight fires from a pool or from rainwater stored in tanks or a cistern.

Blue Ribbon Commission, Times reporting

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee LOS ANGELES TIMES

To reduce water losses and preserve pressure when homes burn and fixtures melt, the commission called for “requiring easy-to-shut-off water valves” in areas accessible to firefighters, or sensors that automatically shut off water flow in high heat. Cheng said DWP has challenged meter manufacturers to develop a device that would allow the agency to activate the shutoff valves remotely if necessary.

When the flames reached the hillside neighborhood of Marquez Knolls in Pacific Palisades, Greg Yost was prepared.

He had equipped his family’s ocean-view house with a firefighting system, installing a pipe from the water main to his rooftop. He bought his own fire hoses and a $6,000 pump to draw water from his pool.

As the January fire spread, Yost climbed onto his roof to spray the flames. When the city water ran out, Yost started pumping from the pool.

A friend helped as Yost directed the powerful stream of water around his yard. He said he was able to save not only his own home, but also those of three neighbors. “The lesson was, pool water is a tremendous resource,” he said.

Greg Yost used a gasoline-powered pump to to access pool water during the Palisades fire, when he fought the flames and saved his house.

The Blue Ribbon Commission agreed, recommending “requiring or incentivizing private properties to maintain accessible water supplies,” such as from a pool or tank, encouraging the installation of exterior fire sprinklers on homes and buildings, and installing connections at the street that fire trucks could access quickly.

By harnessing water at the household level, “we could certainly save more homes,” said Tracy Quinn, a commission member who leads the group Heal the Bay.

This is already standard practice in Australia, where homes in certain high fire risk areas must have storage tanks. And some California counties, such as Sonoma and San Luis Obispo, require certain rural homes that aren’t hooked up to a water system to have a 2,500-gallon tank or pond for fire protection.

In Southern California, experts have discussed expanding existing drinking water systems or building separate infrastructure dedicated to firefighting.

A super-sized drinking water system, with bigger reservoirs or tanks, would make it harder for utilities to maintain water quality. If stored water sits too long, it can lose its chlorination, which in turn can allow the growth of harmful pathogens such as the bacteria that cause Legionnaires’ disease. That’s just one of many complications.

“Building infrastructure is costly and could take a long time and may not be where you need it,” said Marty Adams, a former DWP general manager who is a member of the Blue Ribbon Commission. “Just making the drinking water system bigger isn’t really the most viable solution.”

A message criticizing L.A. Mayor Karen Bass is spray-painted on a wall by a home that burned in the Palisades fire.

One alternative might be to build a separate system to tap ocean water.

San Francisco, for example, has an emergency firefighting water system that was built after the devastating 1906 earthquake. It primarily uses fresh water from a reservoir and two tanks, but it also has pumping stations and equipment capable of drawing salt water from San Francisco Bay if necessary.

Another approach would be to place cisterns scattered across neighborhoods to store non-potable water locally for firefighting — as is done in Tokyo and other cities in Japan.

The commission recommended creating “hyperlocal non-potable water storage” by installing cisterns as parks and schools are rebuilt.

Catching community runoff

Cisterns placed underneath parking lots, parks or open spaces in a neighborhood could store rainwater runoff for firefighting.

Underground

cistern system

Underground

cistern system

Blue Ribbon Commission, Times reporting

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee LOS ANGELES TIMES

“When I drive through my neighborhood, there are plenty of little park spaces, public spaces, where you could put a really large cistern that firefighters could tap into,” Quinn said. Such cisterns typically would be installed underground, and could also be designed to capture rainwater.

“There’s a bunch of things that could be done that don’t cost an arm and a leg,” Gold said. It’s troubling, he added, that local and state agencies have made little progress implementing the commission’s recommendations so far.

Fire crews typically use tanker trucks to bring water, and also rely on helicopters and planes to drop water and retardant on fires.

During the Palisades fire, for example, helicopters refilled at DWP’s Hollywood, Lower Stone Canyon and Encino reservoirs. But high winds initially grounded helicopters while the fire spread. One way to quickly deliver water where it’s needed would involve deploying portable hose-like pipes and pumps.

An Oregon-based company called Wildfire Water Solutions assists local agencies by setting up miles of flexible pipes equipped with portable pumps. The company’s collapsible pipes can be unspooled, connecting any available water source to a fire zone up to 50 miles away. A single one of these portable 10-inch-diameter pipes has the capacity of seven standard fire hydrants, according to the company.

In August, DWP hired the company to set up its temporary pipes to transport water when repairs at a pump station interrupted water service for thousands of residents in Granada Hills and Porter Ranch.

DWP is now pursuing a $4.7-million, one-year contract with the company to assist when infrastructure issues arise. The L.A. and L.A. County fire departments, however, have not contracted the company to assist with firefighting.

A pool sits next to lots where homes were destroyed by the Palisades fire in Pacific Palisades.

Although experts have offered an array of options for improving water infrastructure to protect against big fires, questions remain about which options officials and residents will support, and how much they are willing to invest.

Researchers say the costs of expanding and improving systems to match the scale of recent disasters would be immense.

Finding ways to foot the bill for such upgrades promises to be challenging, said Erik Porse, director of the California Institute for Water Resources, because it will also require convincing ratepayers who will bear the costs. “I don’t think we’ve really grappled with how much water system charges and bills and rates could increase.”