Arthur Boyd looms large over Australian art. He painted religious figures against the Australian landscape; white gums on the Shoalhaven River; monsters and myths.

While he is undoubtedly one of Australia’s most famous artists — his pieces sell for as much as $1.95 million — his legacy runs beyond his work.

In 1993, he and his wife Yvonne bestowed their rural property Bundanon on the Shoalhaven River, near Nowra on the NSW south coast, to the Australian public.

Today, it hosts his historic homestead and studio as well as an art gallery, including a collection of more than 1,200 works by Boyd, his family and other artists, including Sidney Nolan and Brett Whiteley.

A new exhibition aims to tell the story behind Arthur Boyd — of the women in his family, who encouraged him to become an artist and were artists themselves, as well as the generations of women artists that came after him.

“It’s so interesting to pull out more complex ideas about what makes a family [of artists],” curator Sophie O’Brien says.

“It’s five generations. What keeps that going? It doesn’t just happen on its own.”

This survey of five generations of women artists is The Hidden Line: Art of the Boyd Women, open now at Bundanon Art Museum.

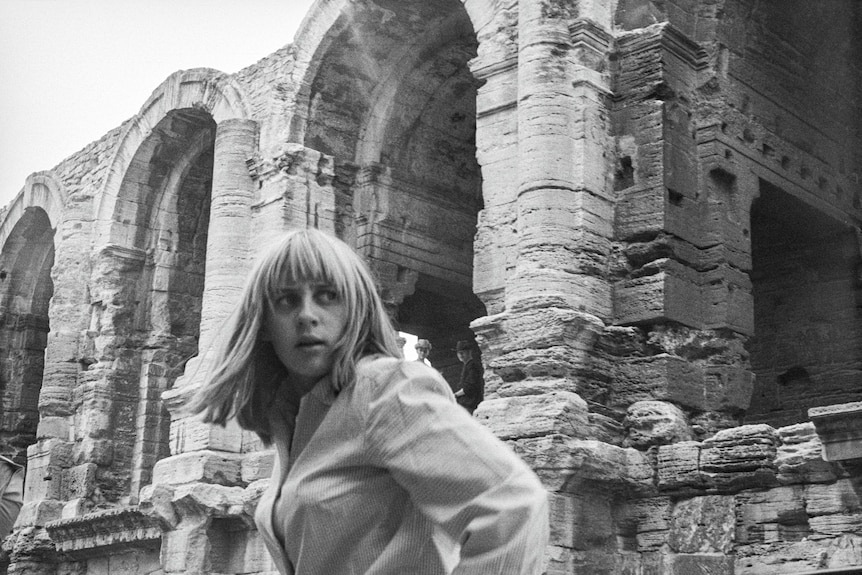

Tessa, Arles by Mary Nolan

Mary Nolan (née Boyd), Arthur’s younger sister, married two artists in her lifetime: John Perceval and later Sidney Nolan, known for his Ned Kelly paintings. But Mary was an artist herself.

She started out painting and making ceramics at Heide and Murrumbeena on Melbourne’s fringe. When she became a wife and mother, she had less time to paint and instead took photographs of her family in their daily lives and on their international travels in the 60s, including threading daisy chains in the grass or brushing their teeth in the river.

“[Nolan’s photography is] an example of how women’s work isn’t seen, or is seen as more secondary,” O’Brien says. (Supplied: Bundanon)

Forty-eight of those photographs are exhibited for the first time at Bundanon as part of The Hidden Line, on loan from the National Library of Australia.

O’Brien dug through a “treasure trove” — six boxes containing hundreds of Mary’s negatives — at the library, searching for photos of the women of the family.

“I’d never seen these photos before,” she says.

“[In Tessa, Arles] is Tessa Perceval [Nolan’s daughter, also an artist], in motion, moving, ready, looking behind, but moving forward.

“It has the promise of the 60s in it, and of Australians being overseas, and that great energy that came from suddenly Australians going overseas and coming back and moving back and forth.

“In terms of photography of this time, she’s thinking in a very immediate, painterly way. The way she constructs an image is very much like a painting.

“She’s documenting, of course, but she makes it a total art form.”

Untitled by Doris Boyd

This jug by Doris Boyd (née Gough), Arthur’s mother, is believed to be the first she ever made, in 1915, at the studio workshop she shared with her husband, William Merric Boyd, in Murrumbeena.

“You can see her painting style really translates from painting to ceramic,” O’Brien says, gesturing to watercolour and oil paintings by Doris that hang on the gallery wall.

“That pot is such a delicate first attempt at thinking about how a form might be decorated differently.”

The jug is painted blue on the inside and features a little metal mend on the handle to keep it together. / Doris Boyd, Untitled, 1915, ceramic. Collection of Lucinda Boyd.

The jug is painted blue on the inside and features a little metal mend on the handle to keep it together. / Doris Boyd, Untitled, 1915, ceramic. Collection of Lucinda Boyd.

Often, Doris would work with Merric on pots like these: her husband would make them from clay, while she painted them, and then the couple would take them to Melbourne to sell.

But to distinguish between ceramics painted by Merric or Doris, one needs to understand Doris’s paintings, O’Brien says.

“We’re trained in looking for a ‘Boyd blue’ or a ‘Merric crazy handle’, but we haven’t got this language [for Doris’s art] because it’s not what’s been repeated to us,” she says.

“[This exhibition asks] What don’t we know? What haven’t we seen? What else could we think about?”

It also draws attention to the way Doris influenced and cultivated Arthur as a painter.

“She’s the one that really helped her son to be an artist,” O’Brien says.

“We’ve got all of his letters to her, saying, ‘Mum, can you give me some money for a canvas?’ or ‘I did this painting today, what do you think?’

“There’s this real sense of mentorship and support and care and financial support for someone to be an artist full time.”

Gum Trees by Emma Minnie Boyd

Emma Minnie Boyd (née a’ Beckett), Arthur’s grandmother, was an artist who often painted landscapes in watercolour. Supported by her mother, Emma Mills, to be a full-time artist, she also painted narrative and religious paintings, in watercolour and oil, and exhibited as far afield as the Royal Academy in London.

But what thrills O’Brien about this watercolour, from about 1914, is how it demonstrates the experimentation and forward-thinking of the Boyd women.

“This one could be made at any time: It could be today, it could be a hundred years ago,” O’Brien says. (Supplied: Bundanon)

It has what she describes as “delicacy of colour” and is brimming with tiny details, rewarding close examination.

“It’s like an abstract,” she says. “This would be her working out something, almost privately. It’s a study of working out how to look and see; [to] use watercolour and look at the landscape.”

O’Brien reckons it’s likely the watercolour was painted en plein air (outdoors).

Still, as a woman, Emma Minnie wasn’t allowed to join the Box Hill artists, including Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, as they camped on the outskirts of Melbourne from the mid-1880s, painting the rural landscape.

“En plein air painting, outdoor painting, we think of it as a European tradition, but it’s the most obvious thing to do in Australia is paint outdoors,” O’Brien says.

“The weather’s good enough that you can sit out, but also, landscape is so key to who we are. You get this energy of being outside and wanting to capture it. I think that’s a pretty good idea of how the family all painted at the time.”

Melbourne tram by Yvonne Boyd

Yvonne Boyd (née Lennie), Arthur’s wife, painted Melbourne tram in 1944, the year before they married. They had met in drawing class four years earlier.

Later, Yvonne became Arthur’s business manager and the mother of their three children — who also feature in The Hidden Line — and mostly stepped back from painting.

“She’s really quite talented and imaginative, but she just doesn’t end up being an artist,” O’Brien says. “Lots of people don’t end up being artists.” (Supplied: Bundanon)

“We only have two paintings, so she actually didn’t make a lot of work,” O’Brien says.

“But you can see she could have absolutely been an artist, but she stops, and she’s supporting an artist and supporting her children, who all turned into artists.”

In Melbourne tram, Yvonne is part of the tradition of Australian artists, including Albert Tucker, Sidney Nolan and Charles Blackman, who, in the 40s, used their art to illustrate the impact of the war.

But rather than painting returned soldiers like Arthur did, Yvonne depicts the effect of the war on the people at home in Australia.

“Yvonne’s perspective is immediate; it’s domestic, it’s relational, and it could be real people,” O’Brien says.

“I love this painting because it really captures the essence of the time, but from a slightly different angle, which is that personal one.

“You can see the difficulty of this time in post-war Australia, where everybody’s got no money, they’re doing powdered eggs, they’ve got rations, and everybody’s struggling to keep it together.”

Horse figure by Hermia and David Boyd

O’Brien admits that she doesn’t know much about Horse figure by Hermia Boyd (née Lloyd-Jones), Arthur’s sister-in-law.

The ceramic from 1966 features sgraffito, a technique of carving through the surface to reveal the colour underneath, while also drawing upon ideas from ancient Greek and Roman sculpture and ceramics.

When Hermia and David worked together in London in the 50s, they were dubbed the “Golden couple” of pottery. (Supplied: Bundanon)

“I just love the idea that it is a vessel; an animal that holds a dish,” O’Brien says.

“It’s just such a dynamic little piece of ceramic, and her playfulness, her elegance, it’s all written into these [ceramics].”

Images of animals — including rabbits, foxes and birds — “animate” Hermia’s ceramics,which she often made with her husband David.

It’s a practice the couple began back in 1950, when they set up their first pottery shed in Sydney, with fellow potter Tom Sanders.

They would go on to work in Italy, England and France, before closing their last pottery workshop on the outskirts of Melbourne in 1968, to focus instead on their individual practices: Hermia on etching and sculpture; David on painting.

Hermia also dabbled in painting, drawing and printmaking.

“She’s constantly trying new things,” O’Brien says. “I just think that playfulness and that energy just comes out in these objects, and this little horse seems to capture it so well.”

The Hidden Line: Art of the Boyd Women is at Bundanon Art Museum until February 15.