Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

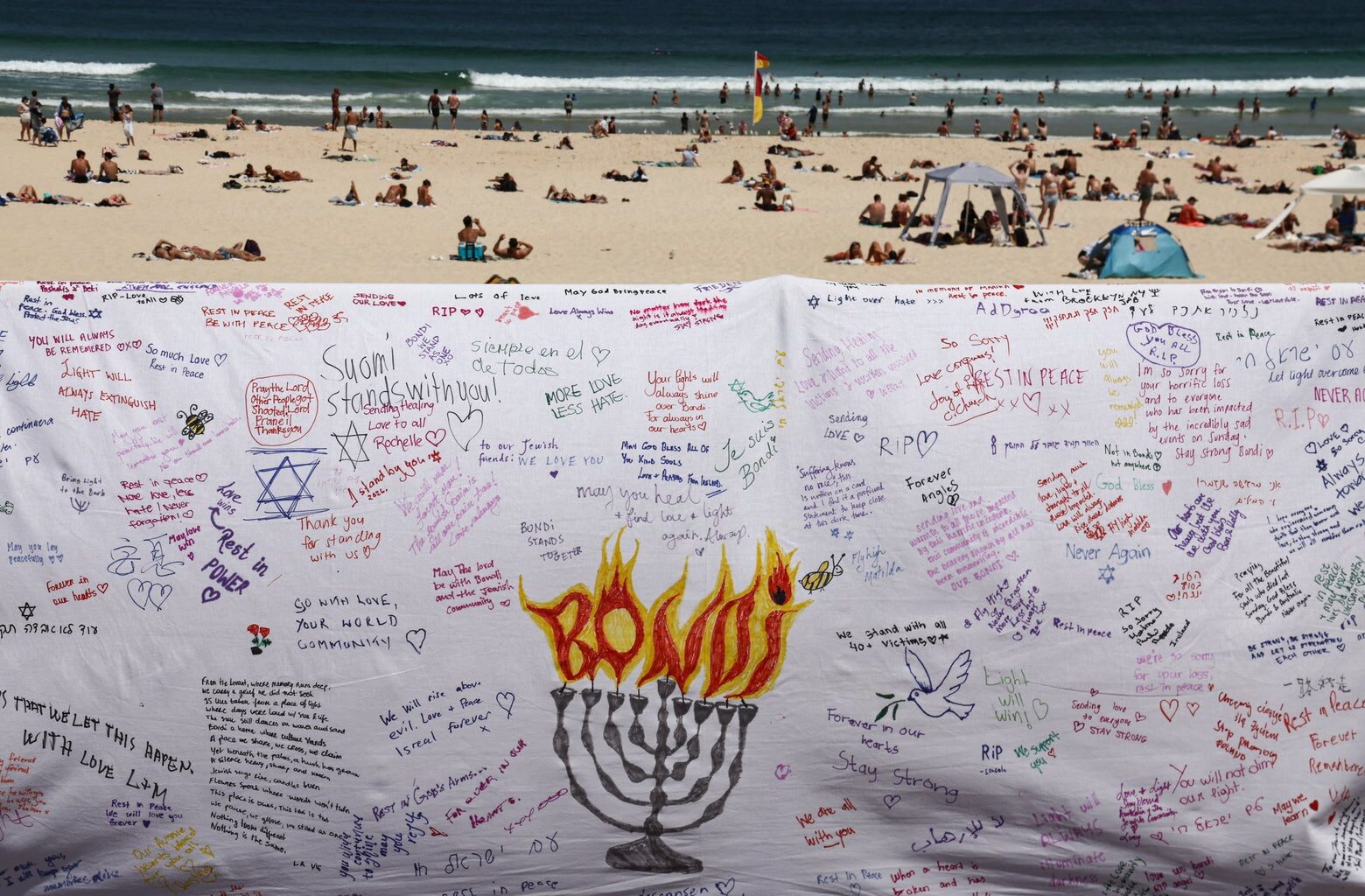

In the past year, a short video was pinned to the social media feed of Chabad Rabbi Eli Schlanger, of Sydney. In that video, filmed last Hanukkah, Schlanger steps out of his home, smiling, announcing: “Here’s the best response to combat antisemitism!” As a song—“Just a Little Bit of Light”—plays, he lifts a large menorah from his car, fastens it onto the roof, lights it, and dances beside it, out in the street. It is a moment of joy, confidence, and trust in the idea that anyone facing bigotry can bring their full self into the public square. This year, at a Hanukkah gathering at Bondi Beach, Schlanger was murdered together with another 14 Jews who had assembled to publicly celebrate the holiday.

Schlanger’s video and his killing point to a question that reaches beyond the Jewish community: Who is able to bring their full identity into public civic life, and what does that say about the society in which we live?

For minority groups—religious, ethnic, racial—public visibility is not merely expressive. It is a measure of belonging. The ability to appear as oneself in shared civic spaces signals confidence that one’s neighbors see that expressed identity as legitimate, accepted, and safe. When visibility becomes dangerous, it is not simply an indication that the minority community is at risk. It’s a sign that the social contract itself has begun to fray.

This is not a theoretical or faraway concern for Americans. As Yair Rosenberg reported in the Atlantic this month, recent surveys show that the generation now coming of age in the United States reflects levels of hostility toward Jews unmatched in any other recent generation. In a 2024 survey of nearly 130,000 Americans, one-quarter of voters under 25 reported an “unfavorable opinion” of Jewish people—with negligible differences between left and right. The Yale Youth Poll found an identical pattern: Younger respondents were dramatically more likely to say that Jews have “too much power” or a “negative impact” on the country.

Across polls, the same curve appears again and again—age, not ideology, is now the strongest predictor of anti-Jewish sentiment. This is not about fringe extremists. It is about the cohort that will shape campuses, media, technology, politics, and public norms in the coming decades. By default, then, this is the cohort that determines Jewish safety in public spaces. Notably, the killers at Bondi Beach were a 24-year-old man and his father.

This all matters because public space is not neutral. It is built and maintained by the people who inhabit it. If younger Americans increasingly view all Jews with suspicion, then the simple act embodied in Schlanger’s video—a Jew standing visibly and joyfully as a Jew—will become harder, not easier, to express in the next generation. His murder forces us to confront the dangers Jews face today, not just in Australia but in the shifting American landscape that now forces us to ask who will feel safe tomorrow.

Jews have been grappling with the relationship between visibility and belonging for generations. In 1978 Rabbi Joseph Glaser, a Reform leader, argued that Jewish rituals should remain confined to private property. Public space, he insisted, should be religiously neutral—a buffer protecting minorities from majoritarian dominance. His approach reflected an era in which safety seemed to lie in discretion.

The Chabad movement, of which Schlanger was a part, came to wider prominence in Judaism under the leadership of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson in the last half of the 20th century and argued the precise opposite: Jews should not disappear themselves, and public religious expression strengthened both Jewish identity and America’s pluralistic character. A menorah in the public square was not a breach of neutrality but a sign that the country belonged equally to all.

These were not theological disagreements. They were different assessments of a democratic society’s capacity to welcome difference. Glaser’s caution and Schneerson’s confidence each assumed something radically different about the U.S.: its norms, its protections, its willingness to embrace or merely tolerate Jewish presence.

Neither view alone determines whether Jews feel safe in public. That depends on society.

Minority visibility is not a minority decision. It is a majoritarian responsibility.

When Jews can gather openly, when they can sing and celebrate without fear, it signals that the country’s commitments—to equality, pluralism, and mutual care—are holding. When they cannot do so, it indicates the opposite—and not just for one group alone.

Ido Kirson and Austin Sarat

People Are Taking the Wrong Lesson From This Weekend’s Dual Massacres

Read More

Only one year ago, Schlanger believed he could answer hatred with light. He believed that public joy was not only permissible but meaningful. His belief did not fail. Society failed him. And that failure raises broader questions: Who gets to feel safe while visible? Whose identities are treated as unexceptional in public life? Which communities must negotiate their presence as a risk?

This Newspaper Editorial Should Be Making Pentagon Leaders Sweat

These questions become even more pressing when set against the growing antisemitism among young Americans. It is tempting to read these trends as destiny, but they are not. Prejudice is not merely a matter of sentiment; it is shaped by the norms that a society chooses to reinforce or neglect. These shifts do not simply describe a generational change—they pose a civic challenge. If belonging in public space can erode, it can also be rebuilt. The responsibility lies not only in confronting hatred, but in strengthening the democratic norms that make visibility safe in the first place.

A healthy democracy does not ask its minorities to calculate whether they can appear as themselves in shared spaces without risking their safety, or even their lives. It does not demand that visibility be balanced against survival. When that comes into question, it signals that something deeper is unsettled: that the norms meant to protect the vulnerable have weakened, and that belonging itself has become conditional.

The burden of ensuring Jewish safety—or in fact the safety of any minority—should never fall on the minority alone. It belongs to all of us. History has taught Jews to protect themselves when others won’t. But the real measure of a society is whether it makes that instinct unnecessary.

Schlanger’s final message remains clear: People flourish when they are able to stand fully as themselves. The question his murder forces upon us is whether the countries Jews call home will choose to affirm or deny that possibility.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.