Summary

Around the world, many people expect China’s—already considerable—global influence to grow over the next decade, and more now view Beijing as an ally or necessary partner.

For much of the world, America is globally influential and will continue to matter, but few people expect it to gain in influence.

In most countries, expectations of Trump are lower than 12 months ago. His first year back in power seems to have caused dramatic shifts of opinion in some places, including India and South Africa.

In Russia, more people now see Europe as an adversary, while views of America have softened. In China, the EU is held to be a power player that strikes its own stances distinct from those of America.

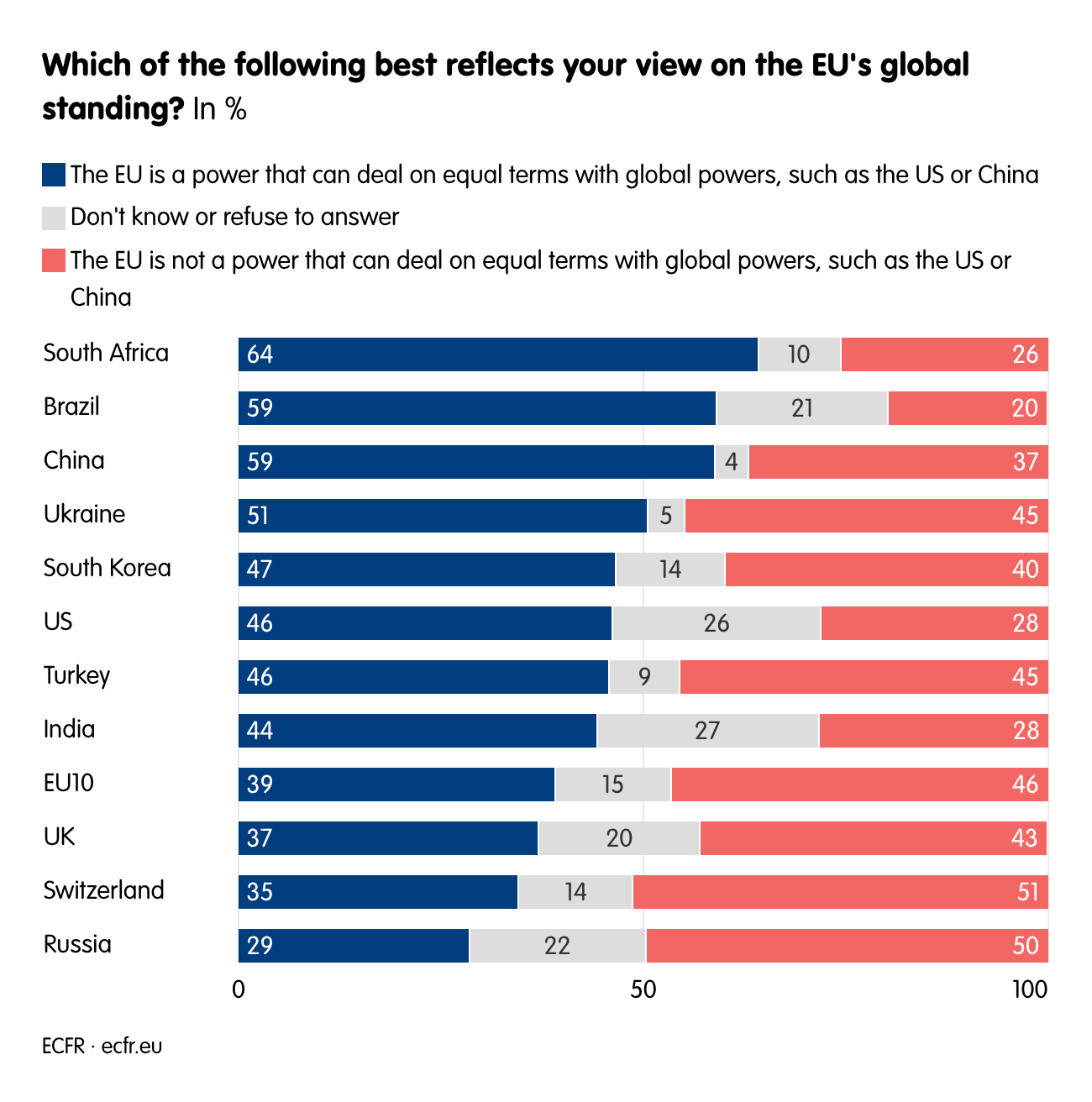

Europeans are the world’s chief pessimists. They lack faith in the EU’s ability to deal on equal terms with the US or China and worry about Russian aggression and nuclear weapons.

European leaders should share greater honesty about where Europe stands in this post-Western, “China first” world in order to devise a successful strategy to navigate it.

Making China great again

Donald Trump did not go into politics to make China great again. But that is what the latest poll of global public opinion from the European Council on Foreign Relations suggests he has done in the eyes of the world.

A year on from Trump’s return, in countries across the globe, many people believe China is on the verge of becoming even more powerful. Even before Trump’s dramatic intervention in Venezuela, his aggressive “America First” approach was driving people closer to China. Paradoxically, his disavowal of the liberal international order may have given people licence to build stronger links to Beijing, since they no longer feel the need to fall in line with a US-led alliance system. Meanwhile, “the West” seems to be a spent geopolitical force for the foreseeable future. America’s traditional enemies fear it less than they once did—while allies now worry about falling victim to a predatory US.

This splitting of the West is most visible in Europe, and in what others think of Europe. Russians now regard the EU as more of an enemy than they do the US; and Ukrainians look more to Brussels than to Washington for succour. Most Europeans no longer consider America a reliable ally, and they are keen to rearm. These are the main findings of a new poll of 25,949 respondents across 21 countries conducted in November 2025—one year after Trump’s triumphant victory in the last presidential election—for ECFR and Oxford University’s Europe in a Changing World research project, the fourth in a series of such global surveys. While the data predate Trump’s operation in Venezuela, many of the trends identified here seem to prefigure it, and one imagines they might even be reinforced by thisintervention.

The world appears to be becoming more open to China; or at least not fear it—an evolution that is in keeping with dominant Chinese interpretations of global geopolitics. As ECFR set out in The Idea of China last year, Xi Jinping and others believe the world is experiencing “great changes unseen in a century”, entailing (although not confined to) a power shift from West to East. One way the Chinese are dealing with this—and with America’s hegemony—is to work with other countries to “democratise international relations” by giving non-Western countries more of a voice. In a global order in which (as this year’s survey shows) publics feel their countries are freer than ever to choose their friends, the results of the poll will be music to the ears of decision-makers in Beijing. For decision-makers in Europe, however, the question is how to live in the truly multipolar world many Europeans have long dreamed of, but perhaps never imagined would take shape in quite this way. They also worry the Venezuela intervention legitimises the idea of China and Russia having their own spheres of influence.

China first

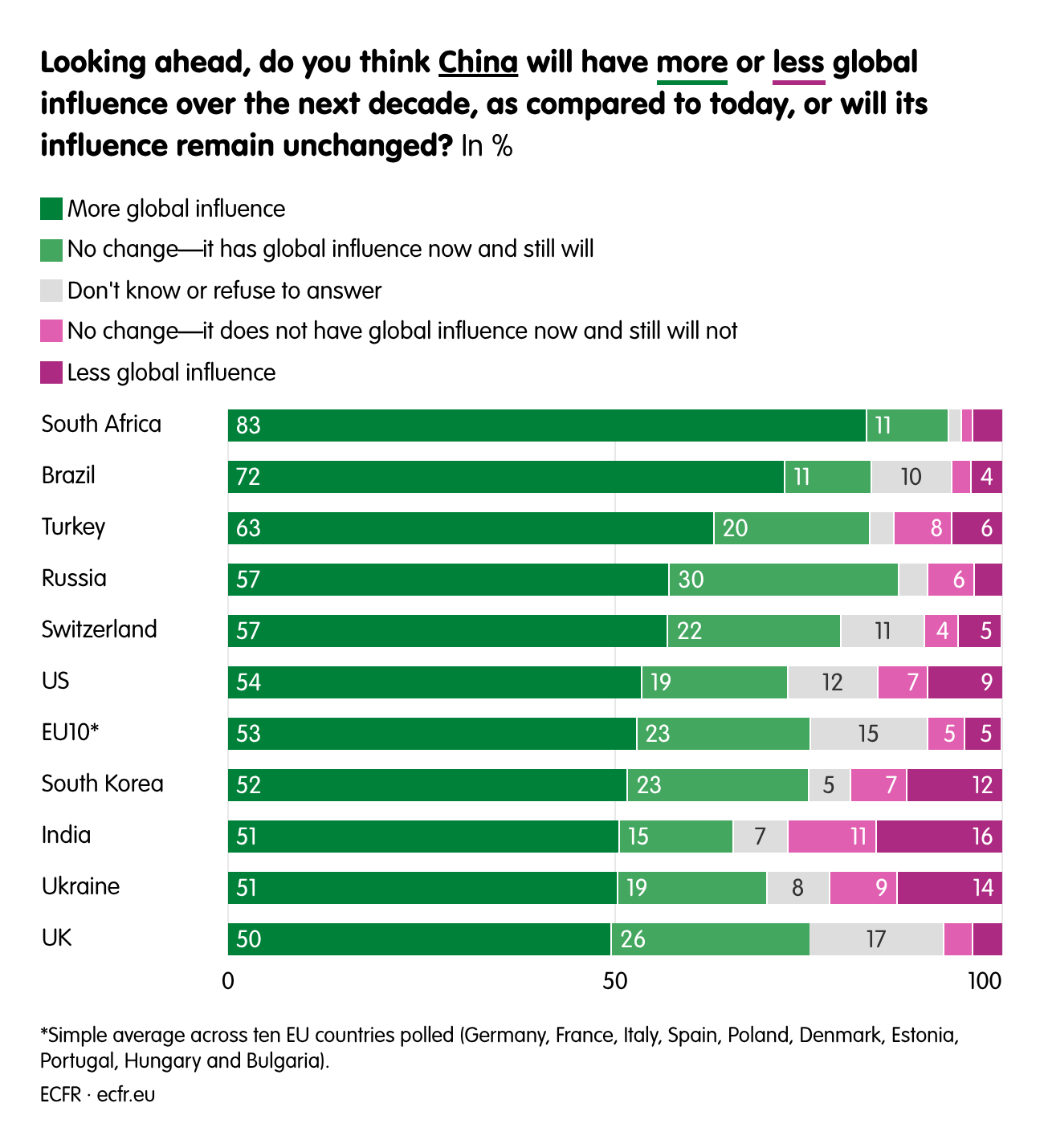

Above all, the findings show that people everywhere expect China’s (already considerable) global influence to grow over the next decade.

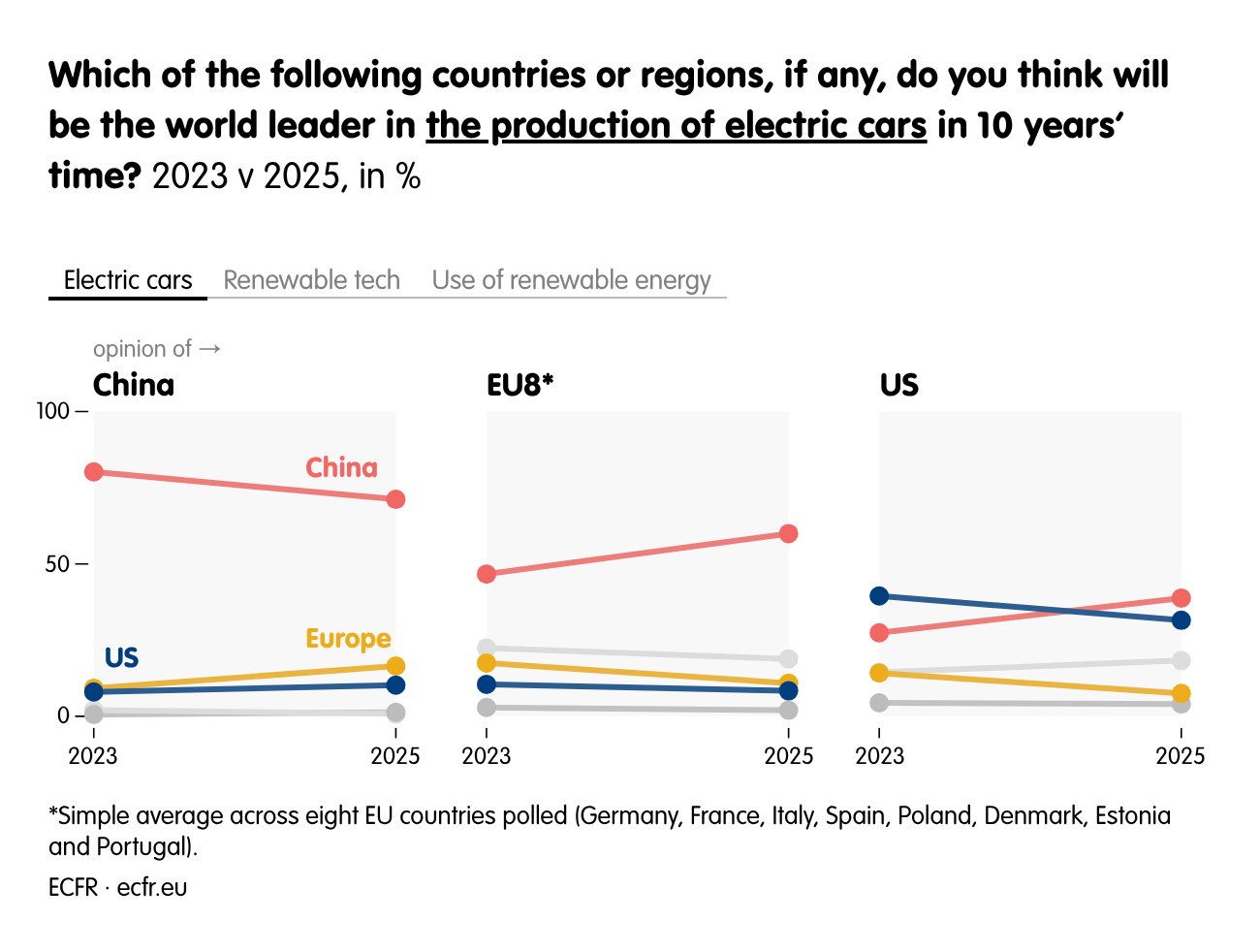

China’s technological success and manufacturing power may be what is driving these perceptions. In the EU, most people believe China will lead the world in making electric vehicles in the next ten years. This is also the prevailing (although still minority) view in America, where, as in Europe, this opinion has strengthened over the last two years. Similarly, the idea that China will dominate in renewable energy technologies no longer prevails in China alone, but also in America and the EU.

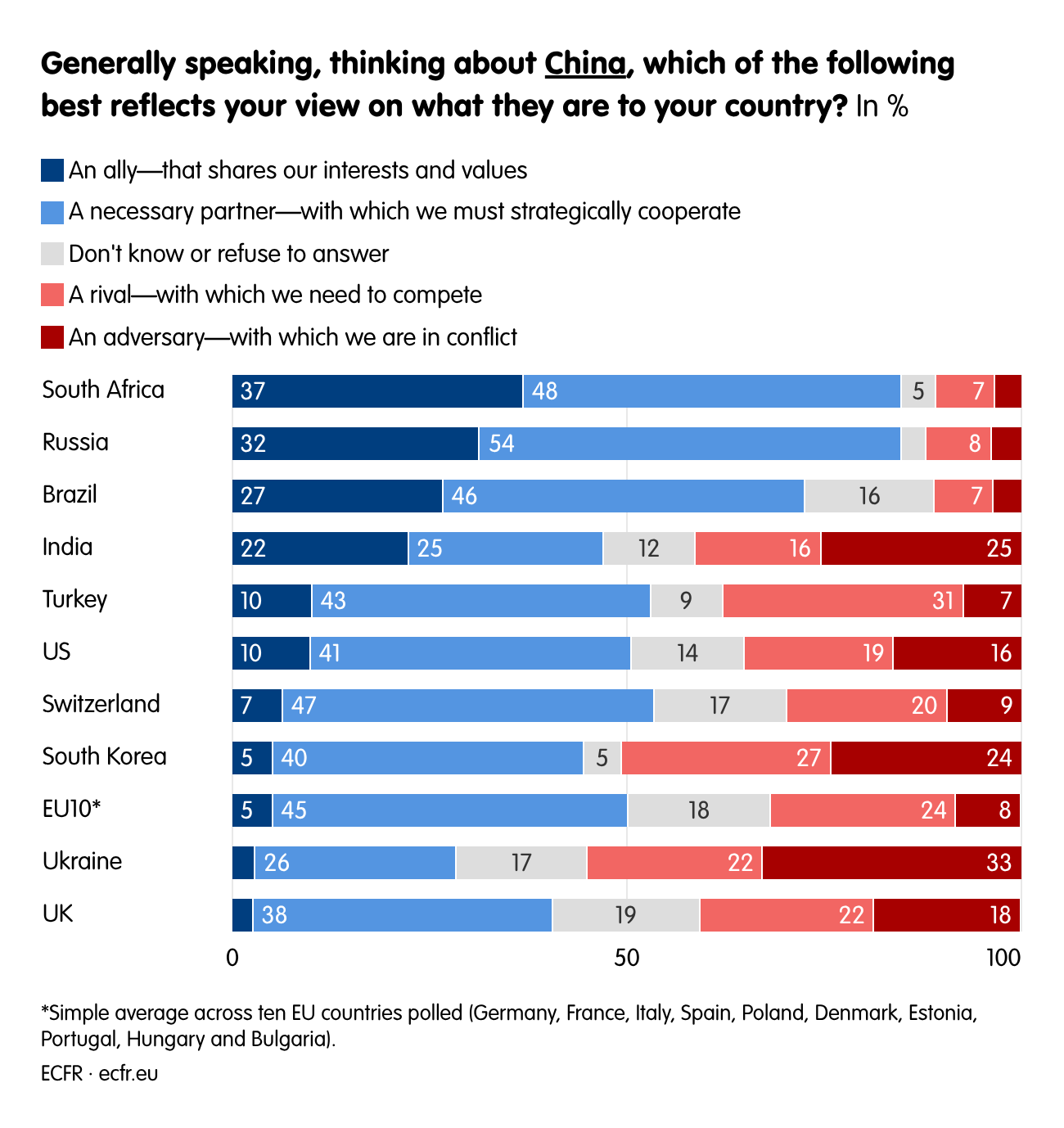

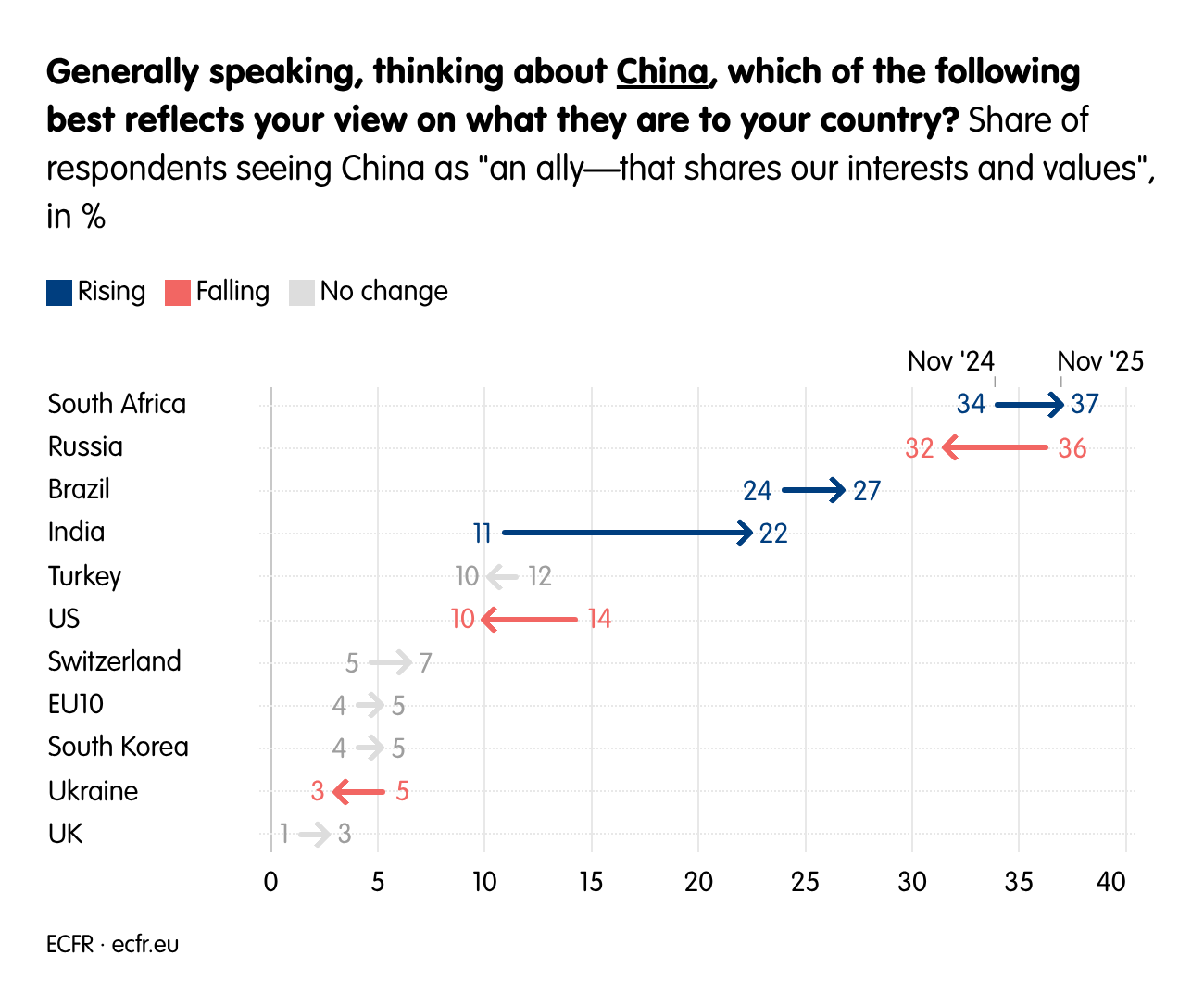

Not only do more people think China is on the rise geopolitically and leading in important industries, but few seem to fear this course of events. Only in Ukraine and in South Korea do majorities of people view China as either a rival or an adversary. Since last year, even more people see China specifically as an ally in both South Africa and Brazil. This turnaround is yet greater in India. Relations between New Delhi and Beijing have traditionally been rocky; despite this, nearly half of Indians see China as either an ally or a necessary partner.

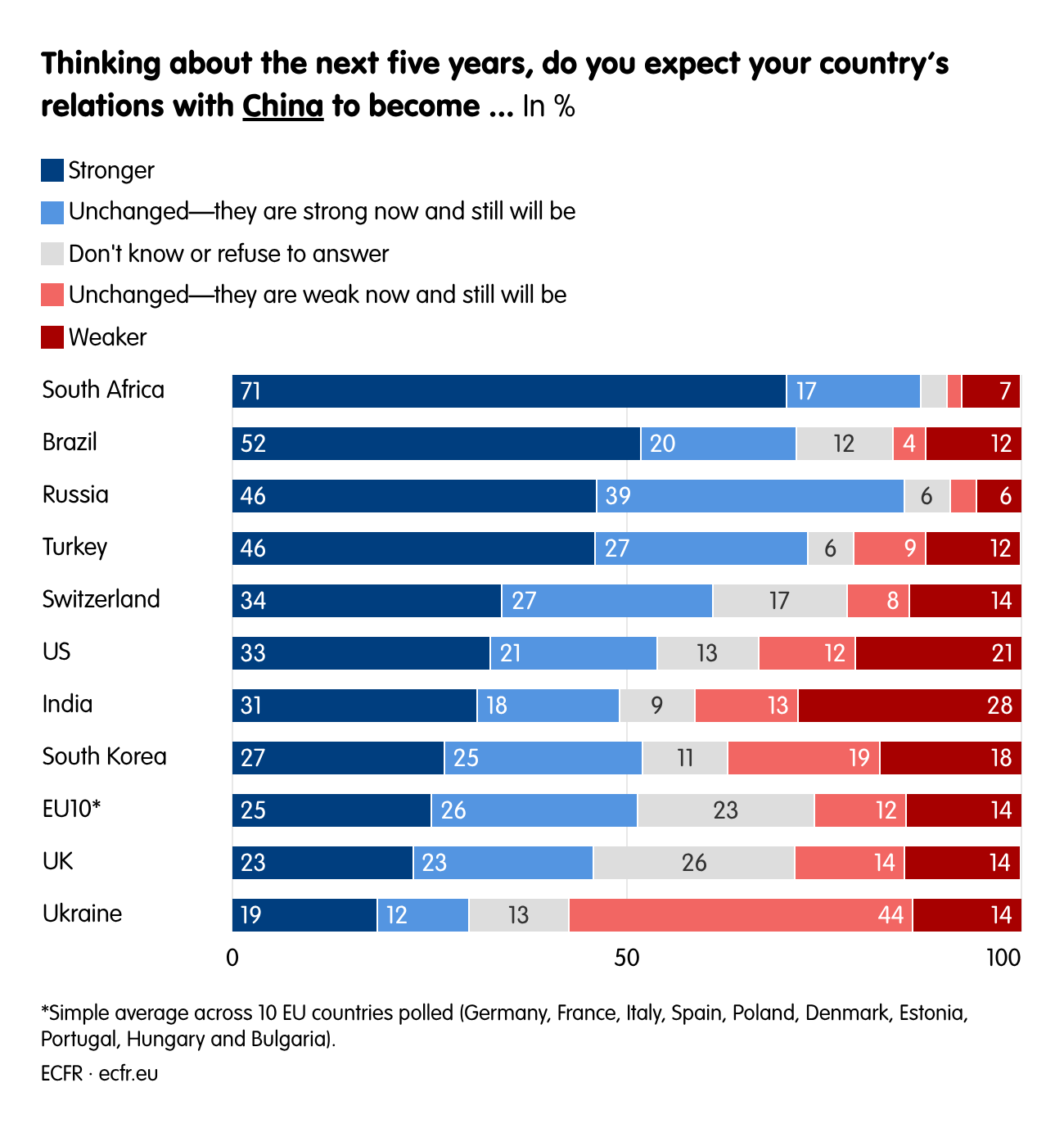

In a number of other places, people expect their country’s relationship with China to strengthen in the next five years: majorities in South Africa (71%) and Brazil (52%) foresee this, as do many in Russia and Turkey. These findings seem to show that, from the perspective of much of the global public, the multipolar order is perfectly compatible with the world of “China First”. In fact, China’s rise is seen as something that suits people living in most non-Western countries. Life without a hegemon is how most people appear to imagine the post-American world.

America in a post-American world

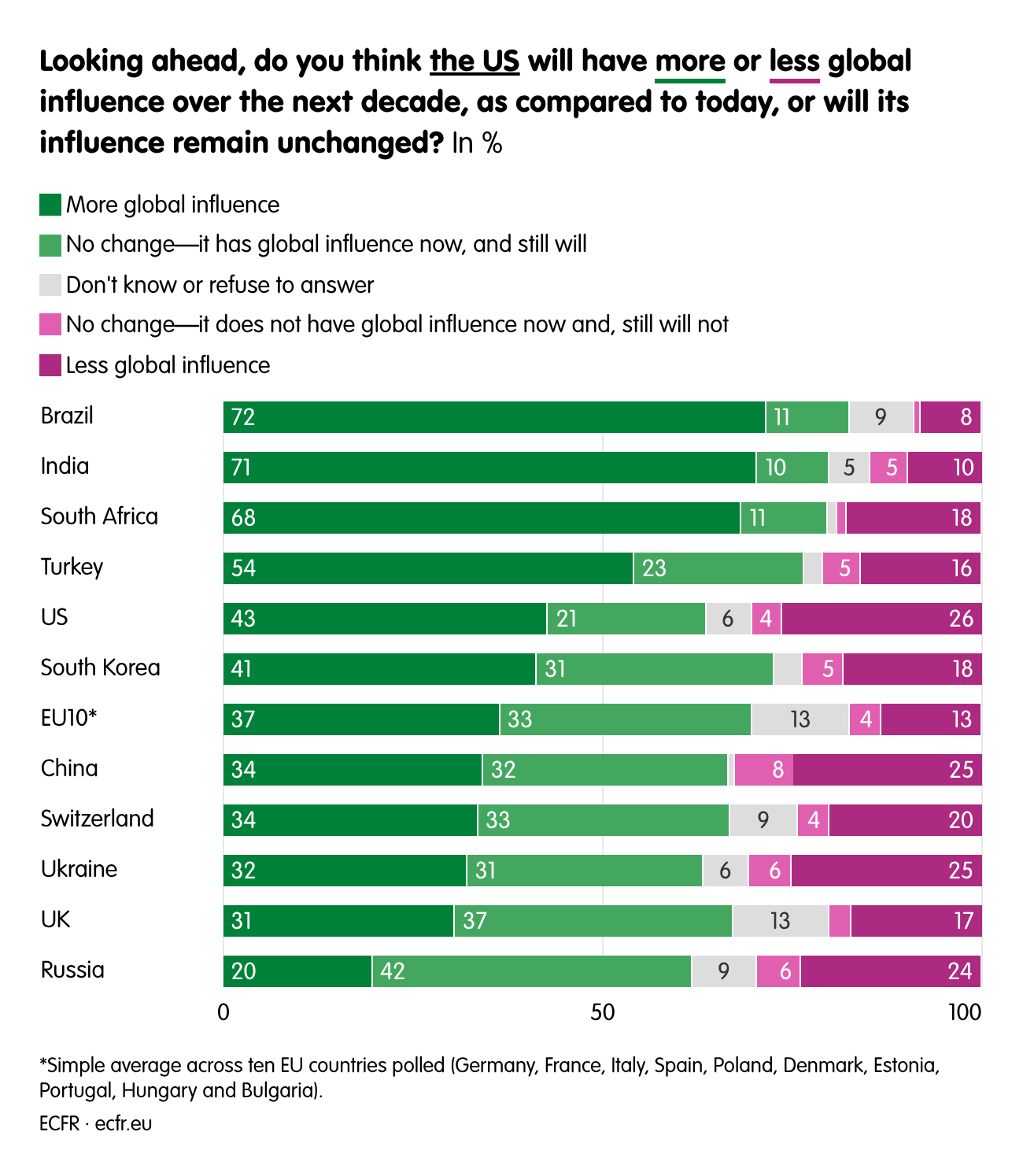

Is China’s rise inevitably leading to America’s decline? “No” is the answer many people give. Only a minority think America will become stronger, but many believe it will still be globally influential. This could reflect a new conception of global power: with the US no longer heading a liberal international order or leading a Western alliance structure, but acting as just one great power in a post-Western world.

Few now expect American power to actually grow: this view musters no majority support among any of Chinese, Europeans, Russians, South Koreans, Ukrainians or even Americans. At the same time, in China, Russia, Ukraine and the US itself, one in four people expect American power to actually decline. Still, for much of the world, the US is globally influential now and will continue to matter, even if they do not think its impact will rise.

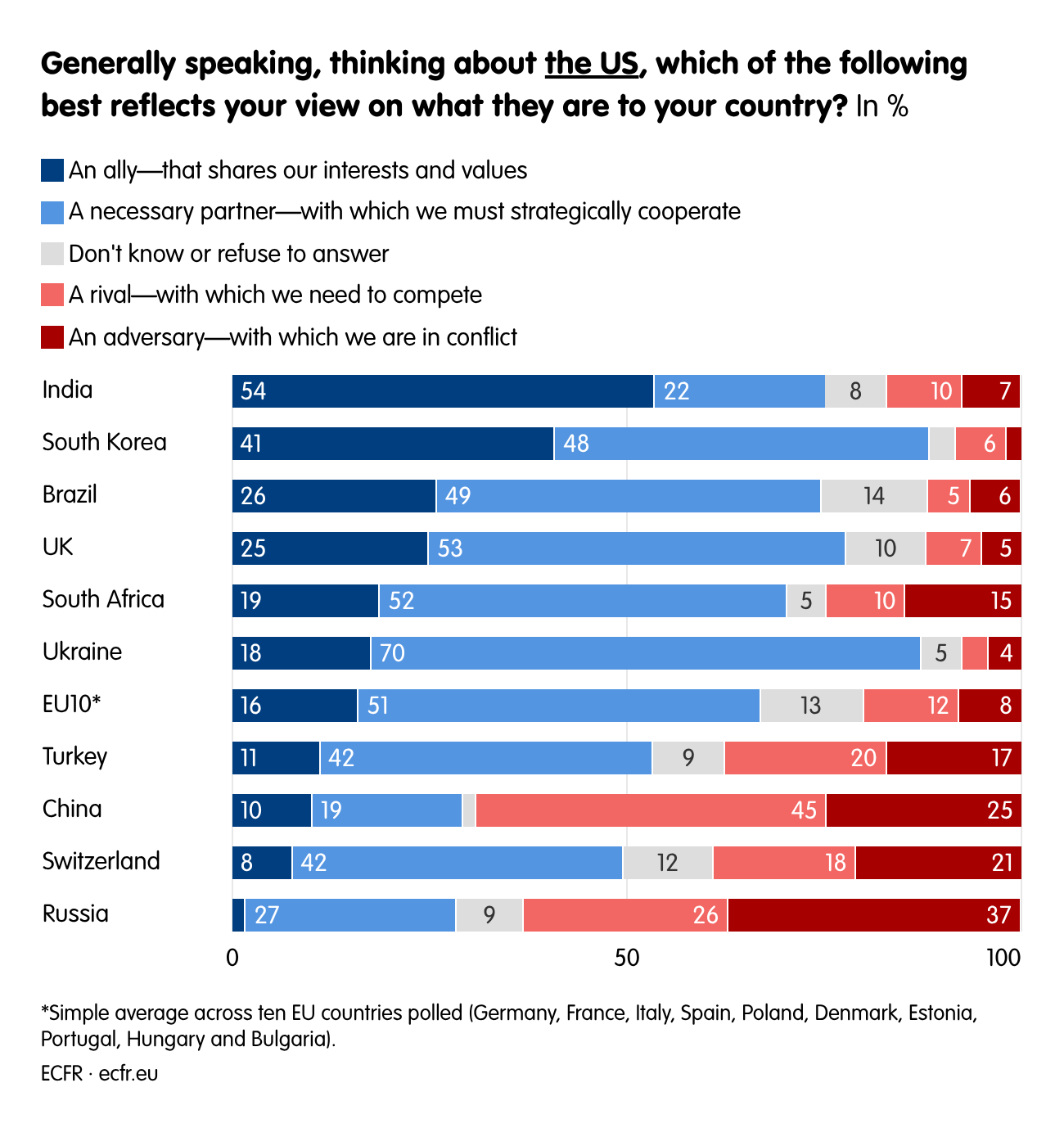

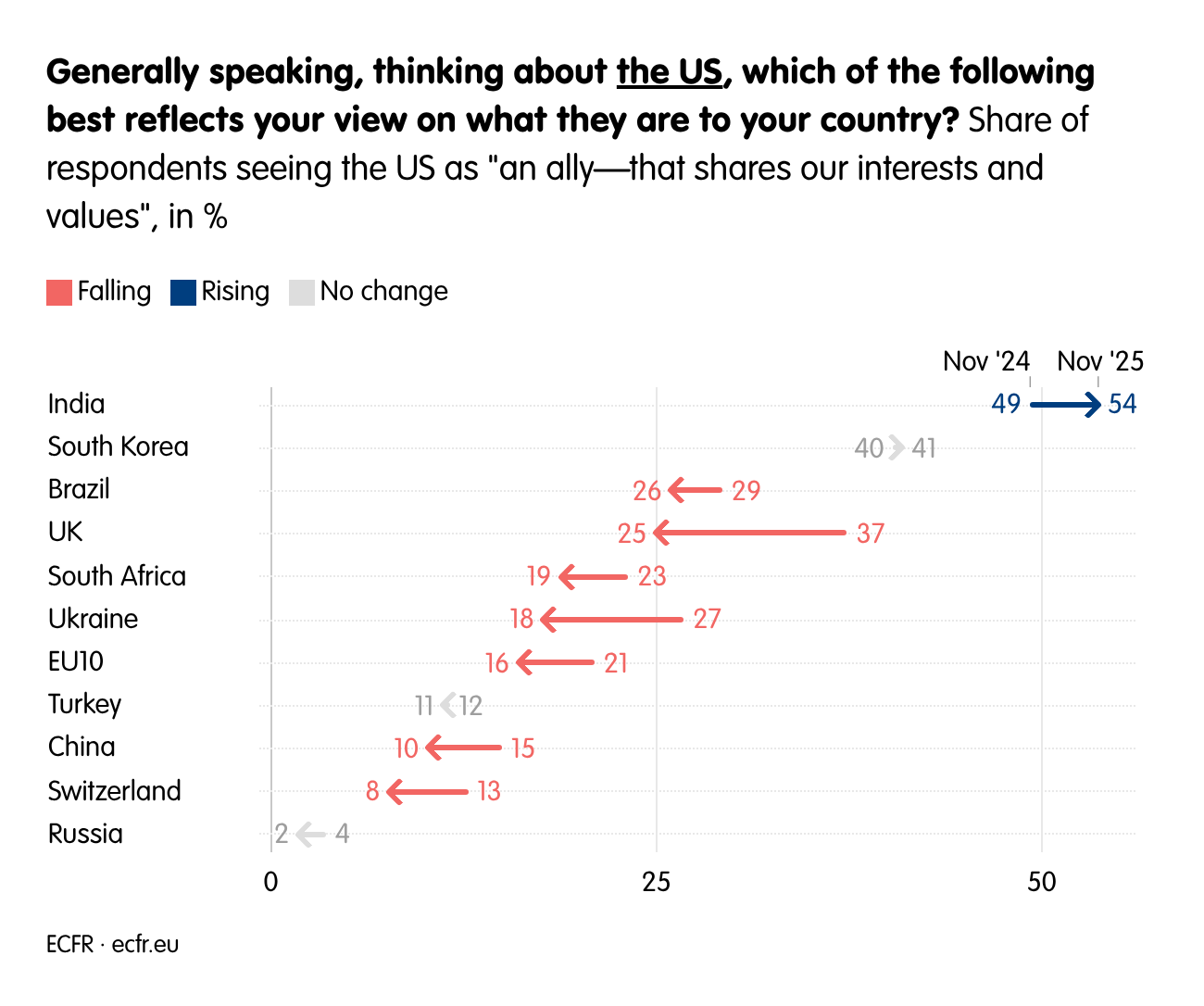

The shifting sands of American power appear to be undermining people’s affinity with the US. A notable fall has taken place among EU citizens, only 16% of whom now consider the US an ally; a striking 20% see it as a rival or an enemy (a view that approaches 30% in some EU member states). This change may be down to Washington’s very public and at times brutal reappraisal of Europe, its politics and its culture (as exhibited last year in Vice-President J.D. Vance’s speech to the Munich Security Conference and the United States’ new National Security Strategy), rather than any real deterioration in American power. In most of the world, however, opinions about America are undergoing a gradual decline rather than collapse. Just as with views of China, countries that think of the US in chiefly negative terms (as either a rival or an adversary) are few and far between—only China and Russia fall into this category. What is particularly eye-catching, however, is the popularity of China among some key middle powers. In South Africa, over a third of people see China as an ally, while only a fifth say the same of the US; in Brazil, similar proportions of people (around a quarter) see China as an ally in the same way they do America.

The only outlier is India—which is, however, unique in that similar proportions of its people see both America (54%) and Russia (46%) as allies.

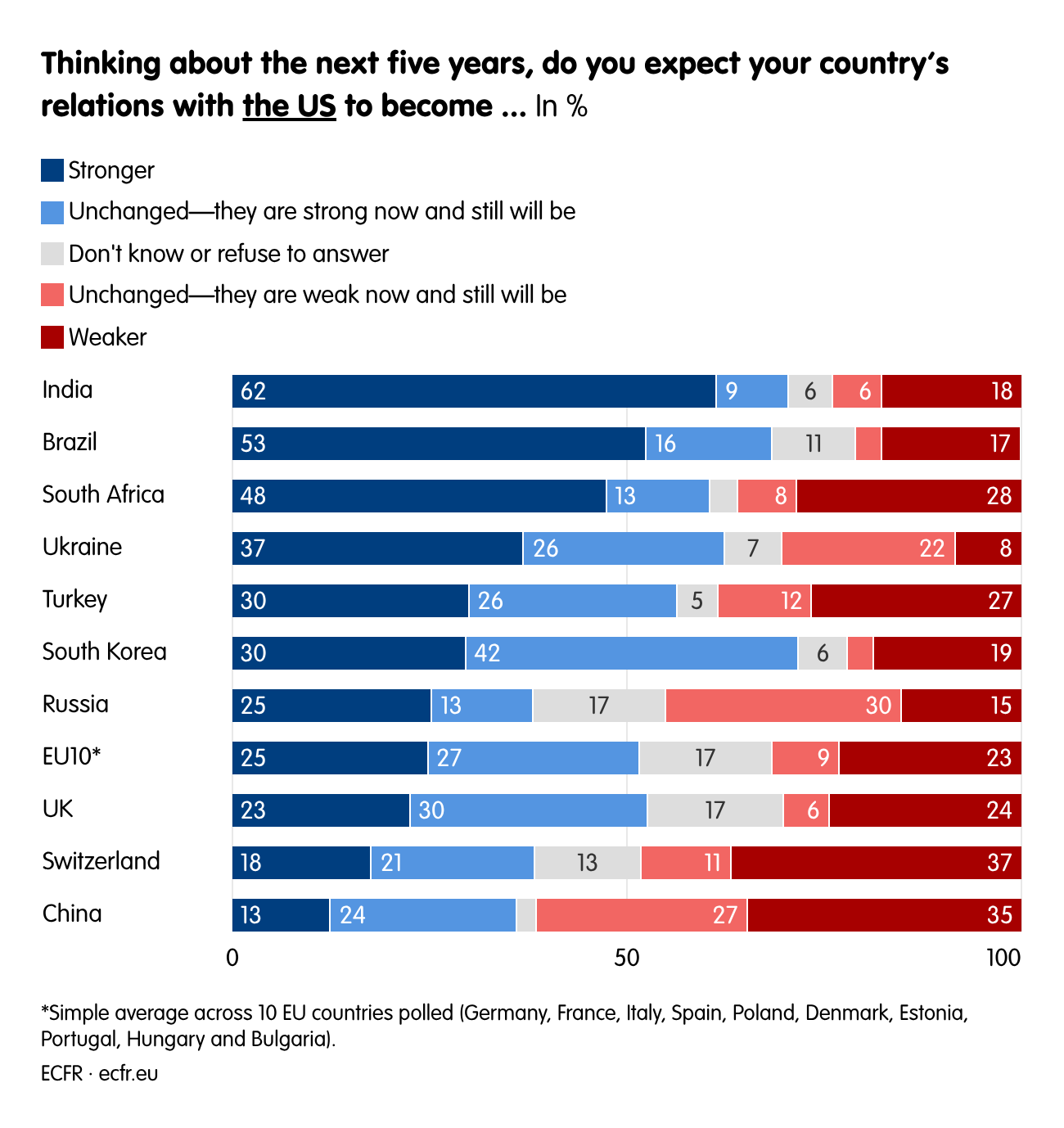

There are still many people in the world—notably in India, Brazil and South Africa—who expect their country’s relations with the US to strengthen in the next five years. (Perhaps in these three countries, this is because people think “the only way is up” after the historical low these relations reached in 2025.) In contrast, in South Africa, Russia, Turkey and Switzerland, more people are expecting positive progress in relations with China than they are with the US. If there is a race for global popularity, America is currently losing to its Indo-Pacific rival.

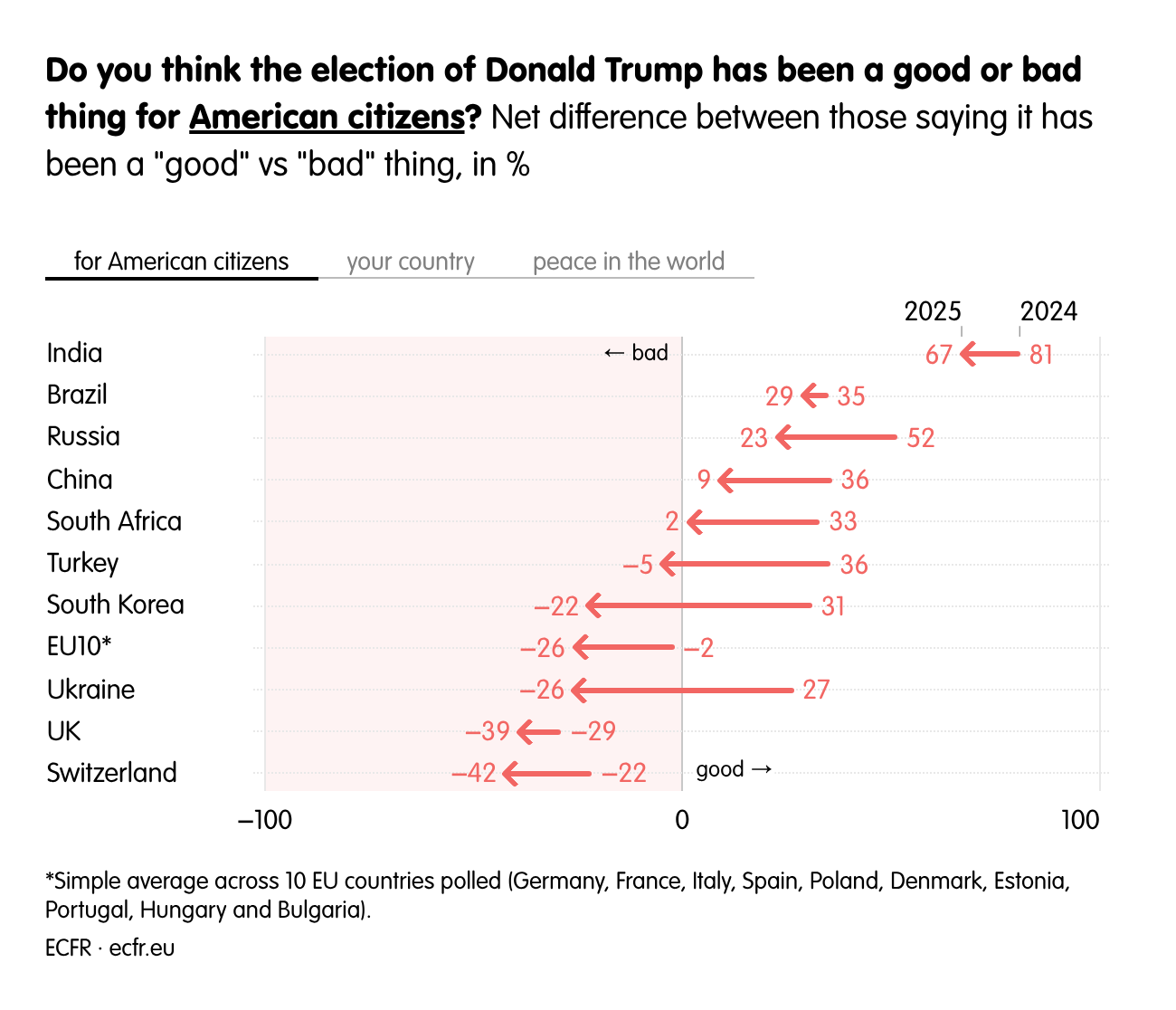

A year ago Trump was a welcome figure in a Trumpian world: people outside Europe and South Korea held very positive expectations about his return. But this Trumpian moment already appears to be over.

In most countries, people have downgraded their expectations of the US president. Fewer people than 12 months ago think he is good for American citizens, their own countries and peace in the world. At the end of 2024, a whopping 84% of Indians considered Trump’s victory that year to be a good thing for their country; now 53% do. The prevailing mood in several countries has shifted from one of broad welcome to broad criticism.

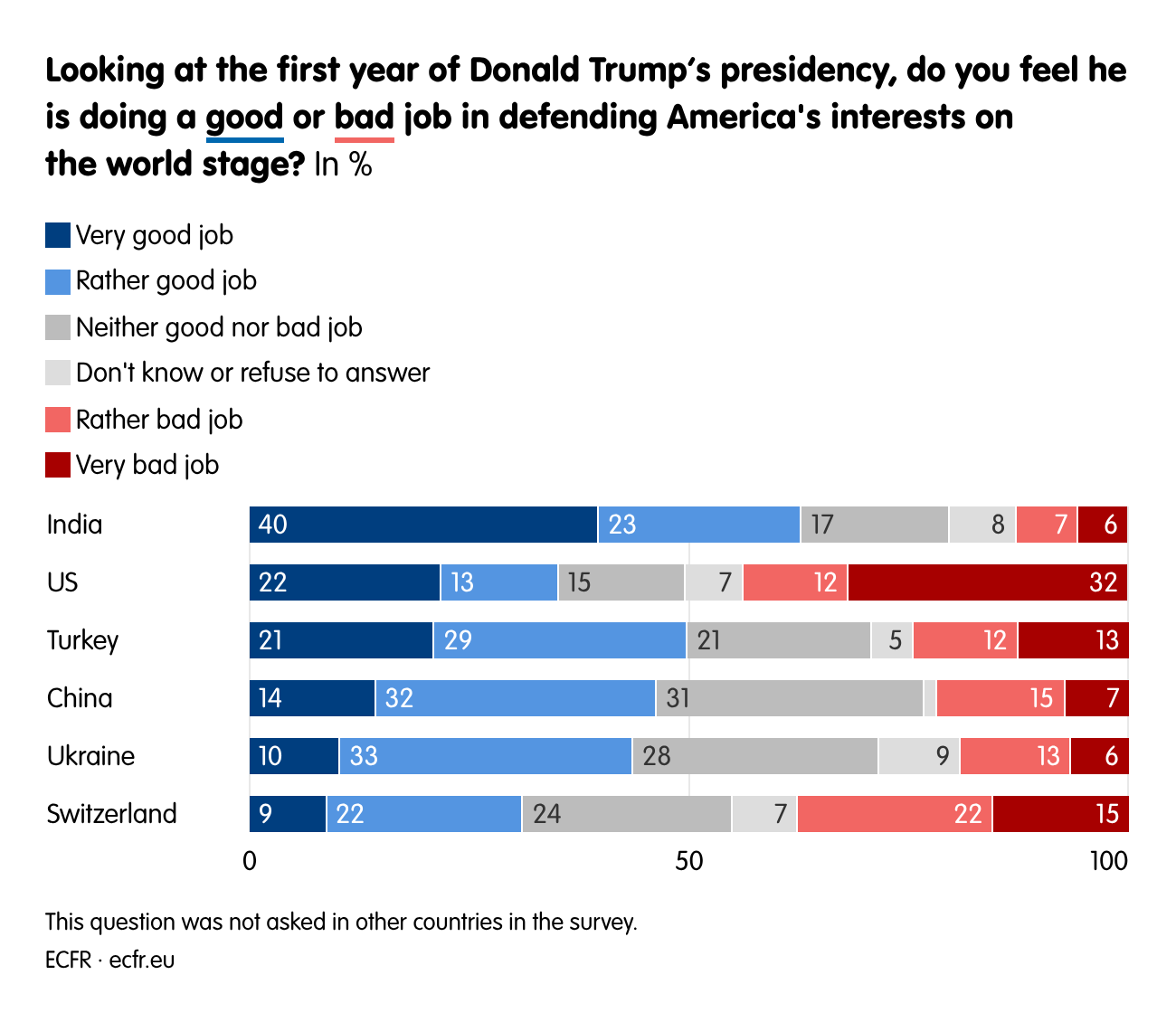

At the same time, in countries as diverse as India, Turkey, China and Ukraine, substantial numbers of people agree Trump has at least successfully defended America’s interests on the world stage. In our last paper, we suggested that the US under Trump was becoming a more “normal” transactional great power, rather than the exceptional “liberal Leviathan” it had mostly been since 1945. This year’s data indicate global publics largely agree.

The true meaning of multipolarity

China’s rise and America’s journey towards “normal” great power status also influence how people view the global order. Under President Joe Biden, the White House talked of a world divided between democracies and autocracies—implying everybody needed to pick sides in a form of new cold war, with China as the principal adversary.

Our data suggest people around the world do not anticipate a bipolar, ideological struggle for primacy. On the contrary, with the US behaving like just another transactional great power under Trump—and China establishing itself as a giant of equal stature—people outside the traditional West seem to expect more room for their own countries to grow and thrive. For them, the multipolar world appears to be made up of many powers, big and small, with the US and China as the two superpowers—but with others freer to move between poles as they wish.

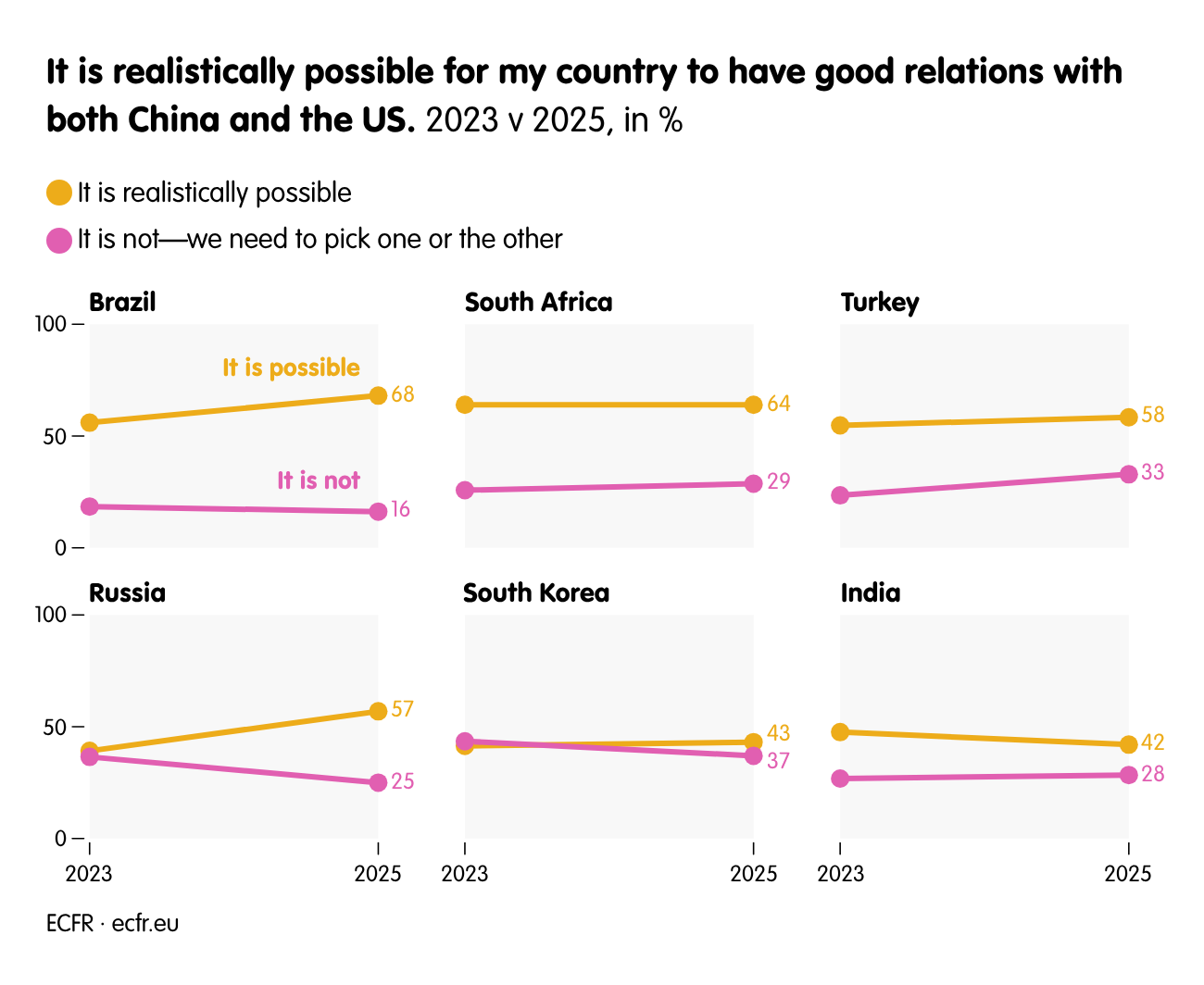

As a result, in many countries that might until recently have tied themselves in knots to avoid choosing between the US and China, citizens now feel they can comfortably maintain good relationships with both powers. Majorities in Brazil, South Africa, Turkey and Russia agree this is “realistically possible” for their countries; such a view prevails in South Korea and India too. This feeling was already present two years ago. But it has only strengthened in some places since then, particularly in Brazil and Russia.

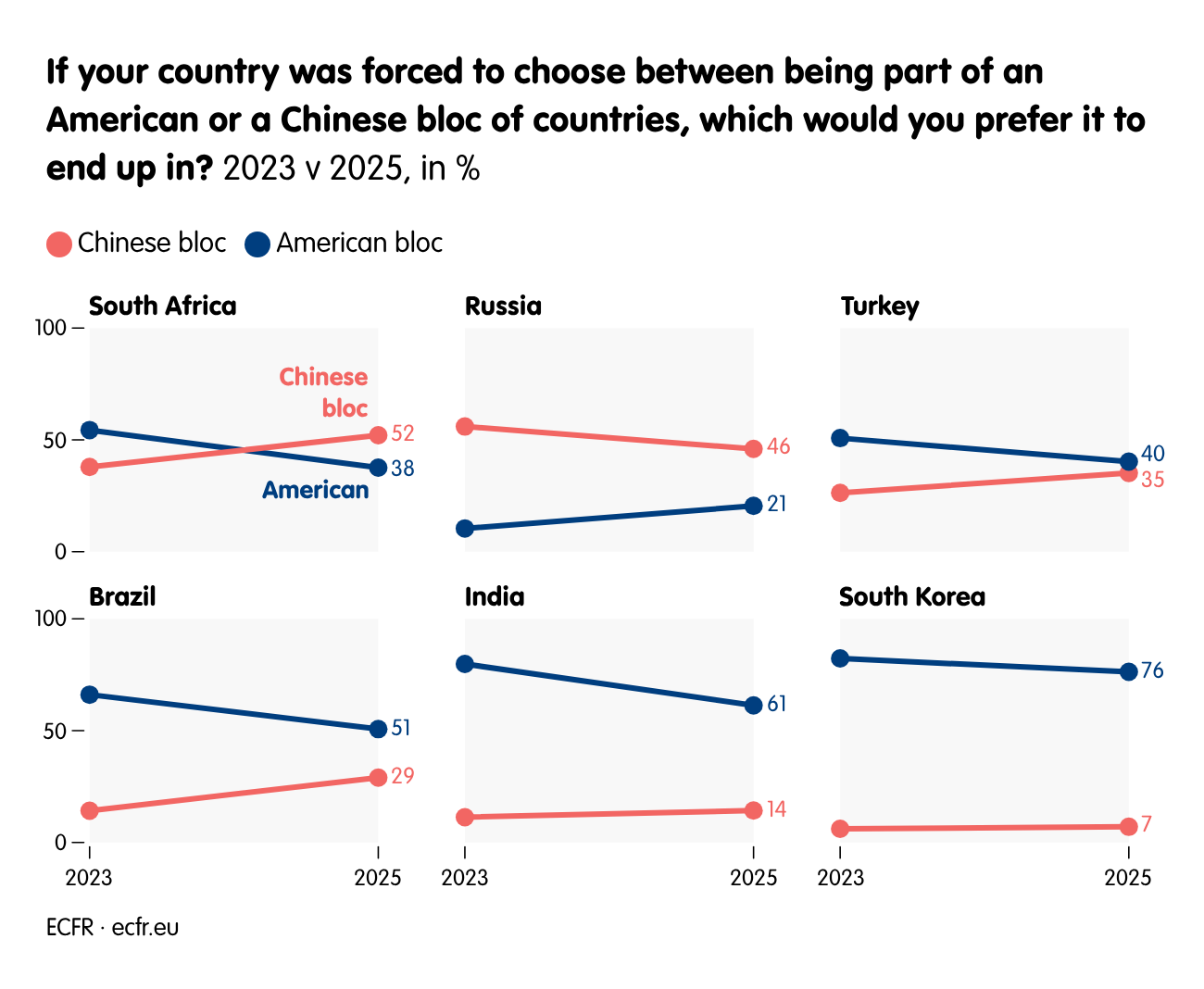

This new order may allow political leaders to worry less about being torn between China and America. When asked which of the two countries people would choose if forced to, many would opt for China. Around half of South Africans and Russians select China over America, but so too do about a third of Turks and Brazilians.

Most Indians and Brazilians still place themselves in the US camp, even following a year in which Trump imposed steep tariffs on their countries. But the story in South Africa is dramatically different. In September 2023, a majority of South Africans said they would choose the US over China—but by the end of 2025 they had upped sticks to join the China camp. Trump’s refusal to invite South Africa to G20 meetings in 2026 will not have passed unnoticed.

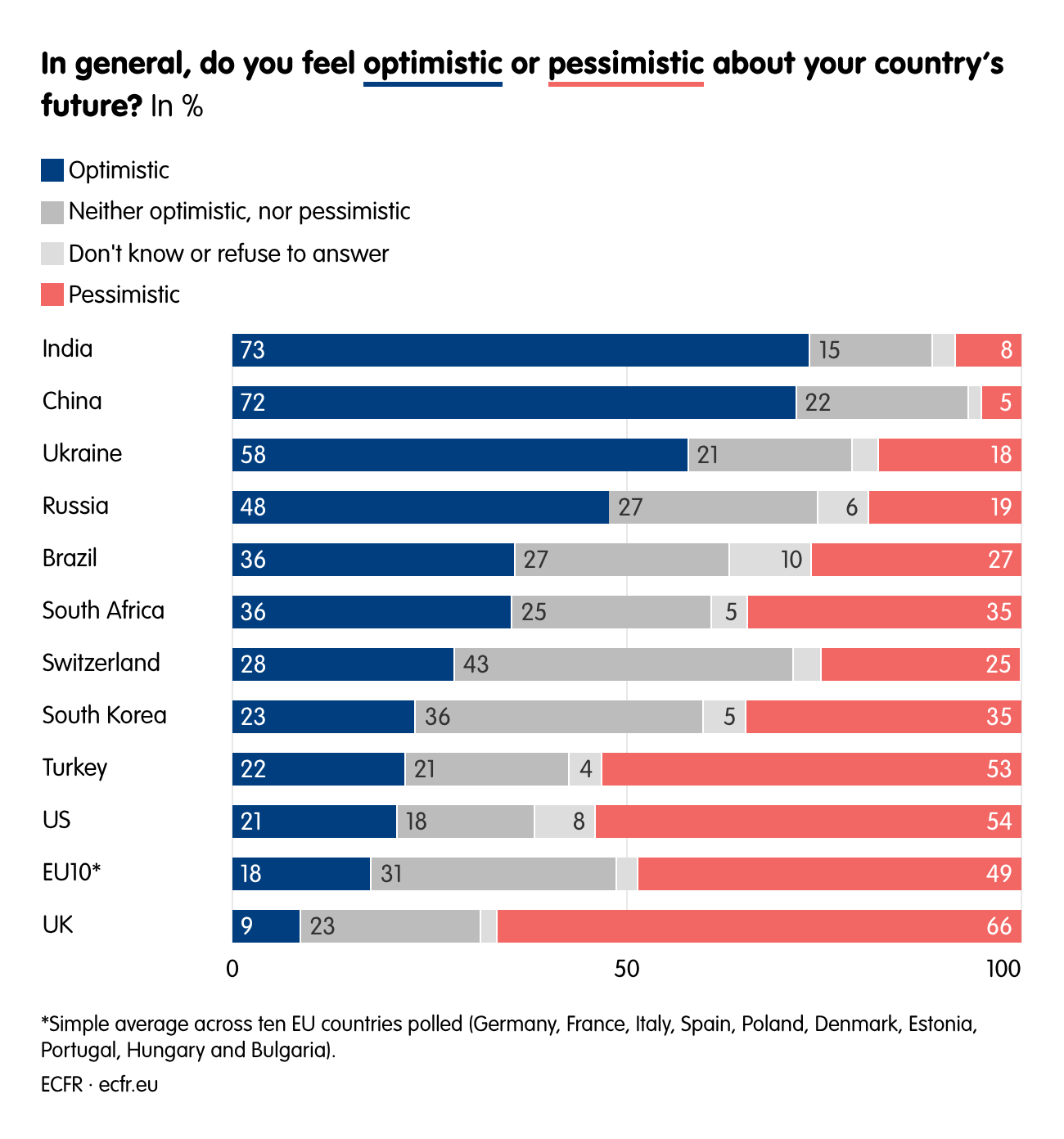

In terms of how people feel about the future, optimism is strong in India and China, where people may feel positive about an increasingly multipolar world and their countries’ place within it. (Optimism is also expressed by 58% of Ukrainians and 48% of Russians, but, given these are countries at war, such data could be driven by hopes for victory.)

Meanwhile, we find what might be called an “axis of pessimists”, centred around a declining America and its jilted allies—chief among them Europeans and South Koreans.

Changing perceptions of Europe in Russia, Ukraine and China

As power shifts in the world, people’s perceptions of Europe are changing too—and in sometimes dramatic ways. As Trump reconfigures America’s geopolitical orientation, others are beginning to regard Europeans not simply as an adjunct to American policy, but as independent players in their own right.

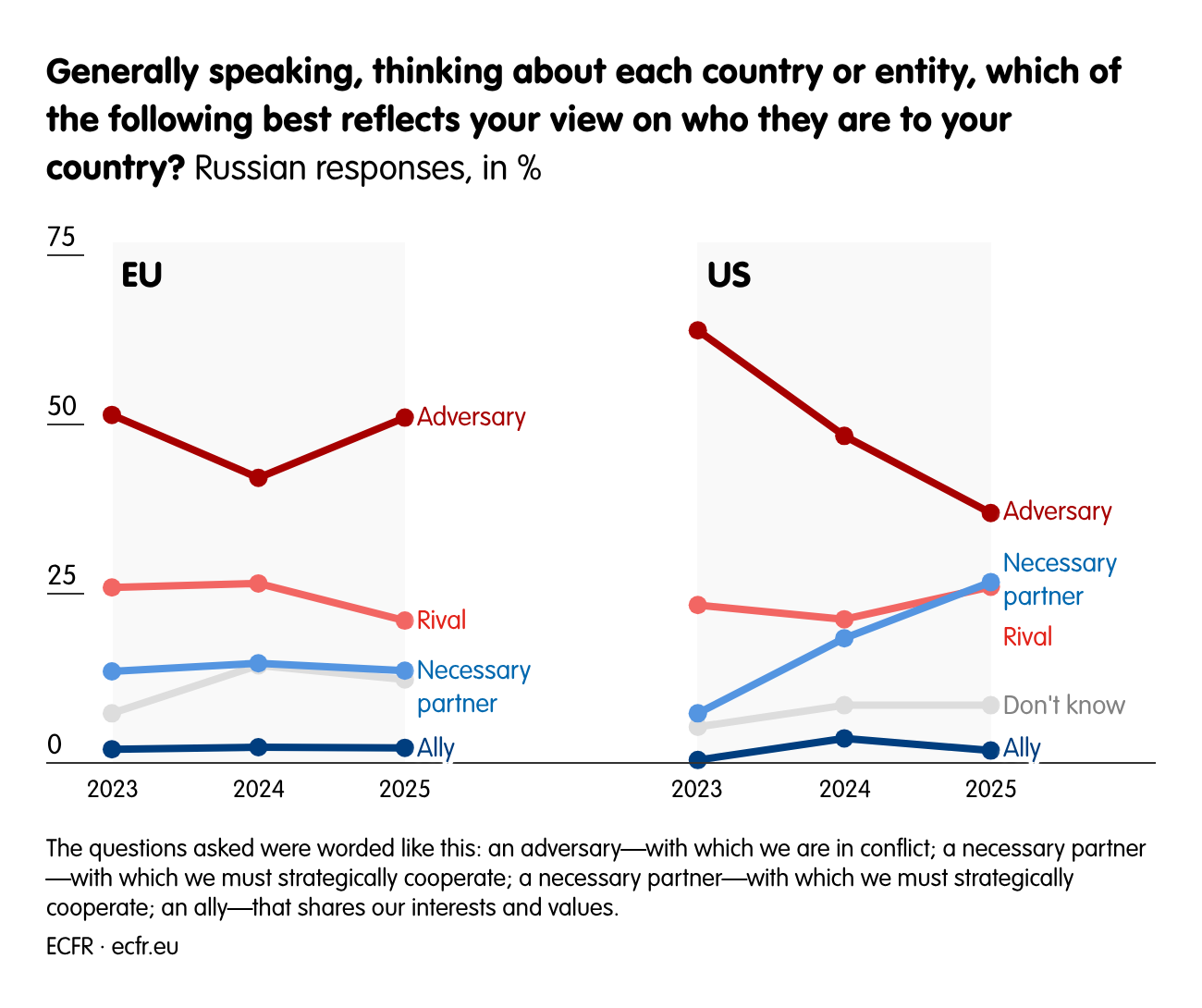

The most dramatic change has taken place among Russians, who see Europe as an adversary they are in conflict with. As the Trump administration has bent over backwards to restore good relations with Vladimir Putin, Russians have become less hostile to Washington and increasingly blame Europe. Fewer people in Russia now consider the US an adversary; just 37%, down from 48% last year, and 64% two years ago. Importantly, it is worth underlining that Russians’ growing sympathy towards the US is not reciprocated in the American public. The prevailing view in America—and among Kamala Harris and Donald Trump voters alike—is that Russia remains an adversary.

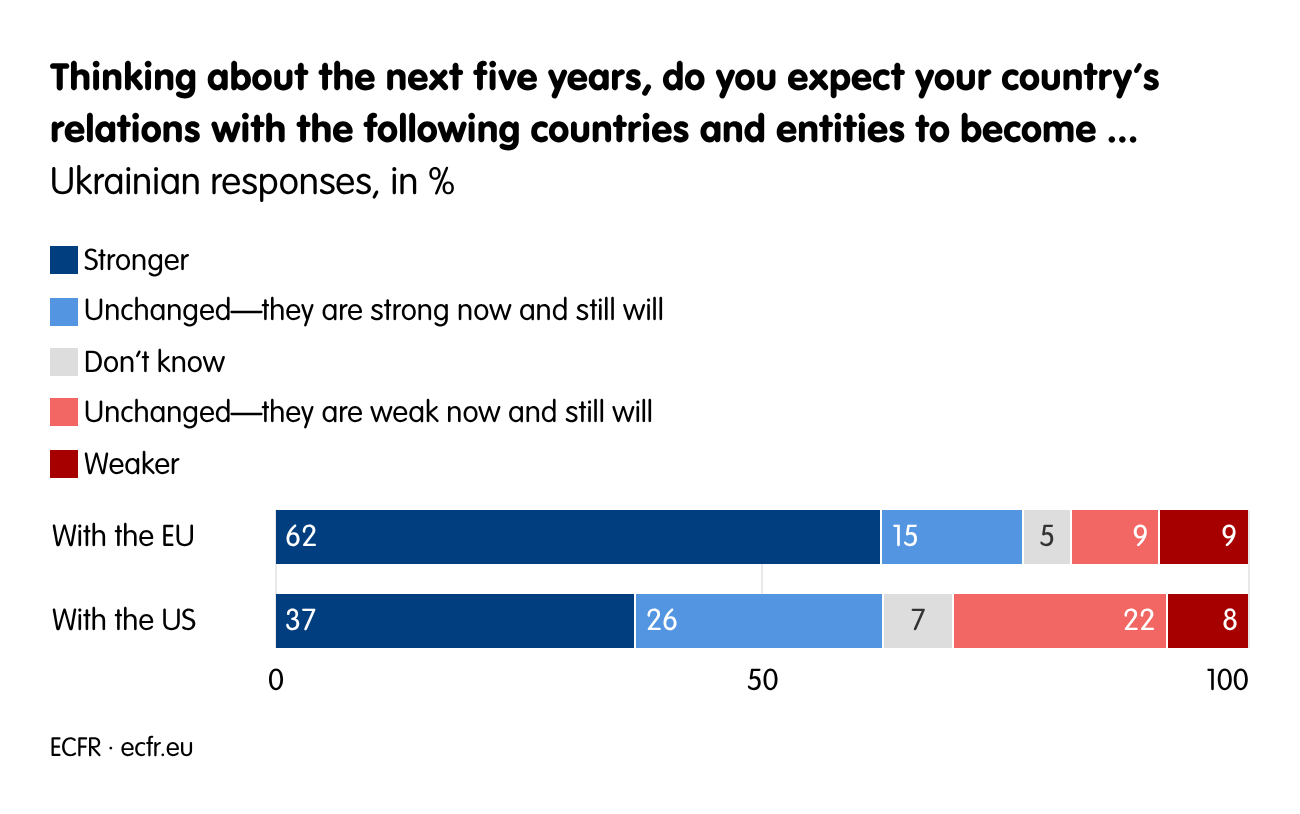

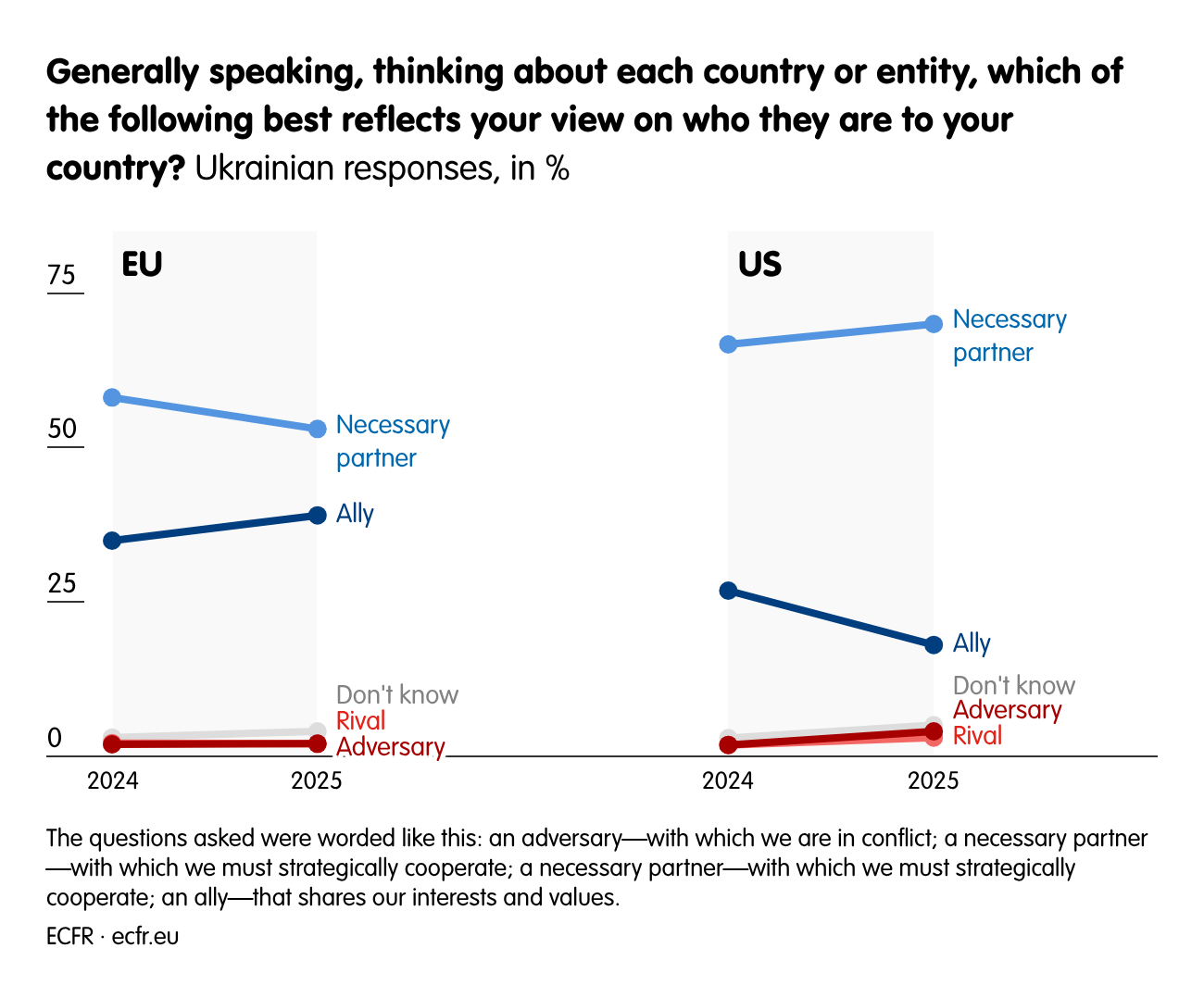

The corollary to this is that Ukrainians, who once saw the US as their greatest ally, now look to Europe for protection.In Ukraine, nearly two-thirds of people expect their country’s relations with the EU to get stronger; only a third say the same about America. Two-thirds of Ukrainians also see US and EU policies on their country as different.

This is a particularly European moment for Ukrainians. Thirty-nine per cent of people in Ukraine consider the EU an ally. Strikingly, only 18% now think the same of the US. The perception of the US as an ally has eroded over the last year, falling from 27%, while that of the EU as an ally has consolidated, remaining relatively stable (35% last year).

The changes in Russian opinion clearly parallel a change in the strategy of the Putin regime. One Russian strategist recently explained to one of the authors that Putin’s strategy is threefold. Paraphrasing Lord Ismay’s famous quip about NATO (that its original purpose was “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in and the Germans down”), he said that Putin’s strategy is to keep the Europeans out, the Americans in and the Ukrainians down. They now see Europeans as their most implacable foes and would like to turn dealing with European resistance into an American problem.[1]

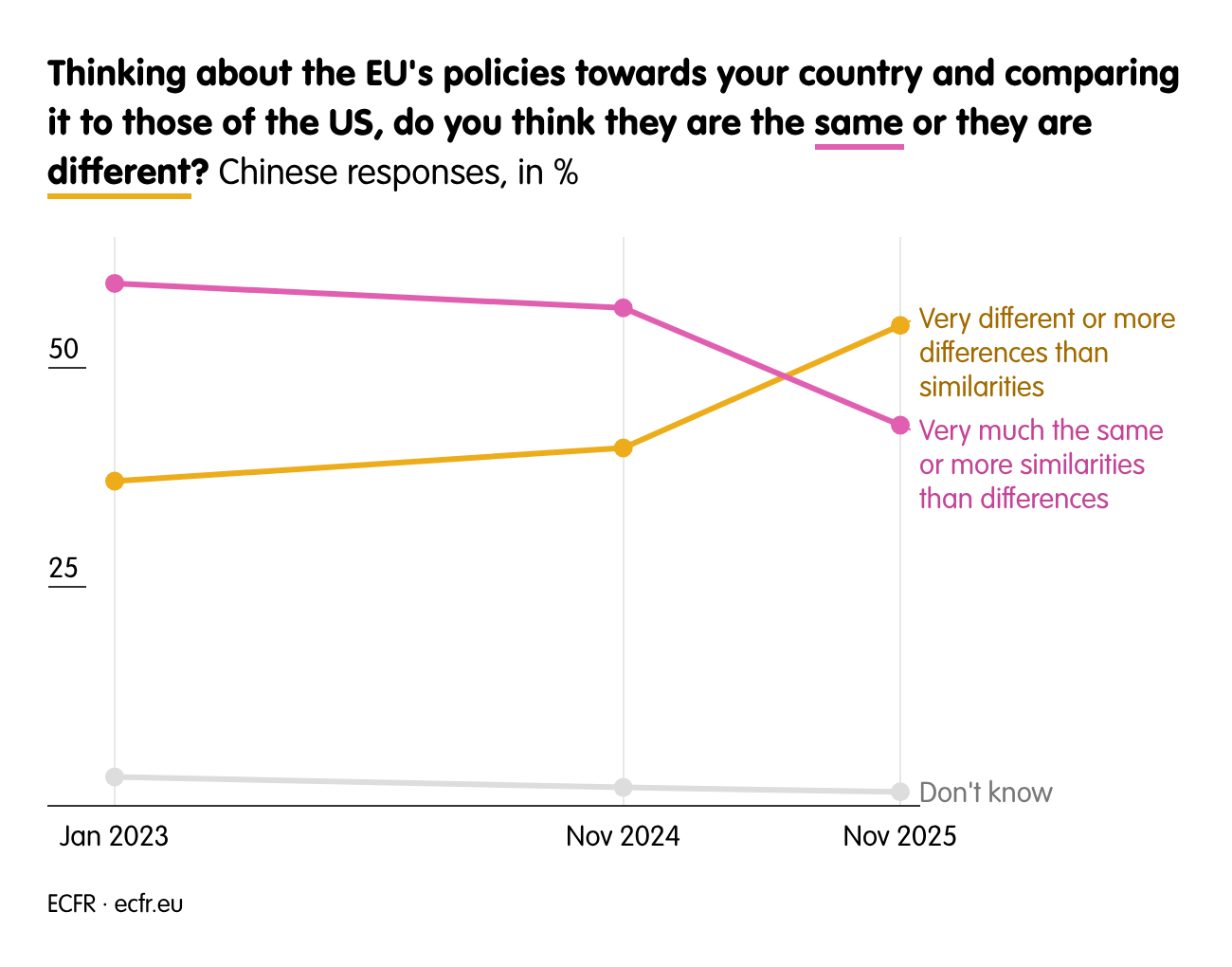

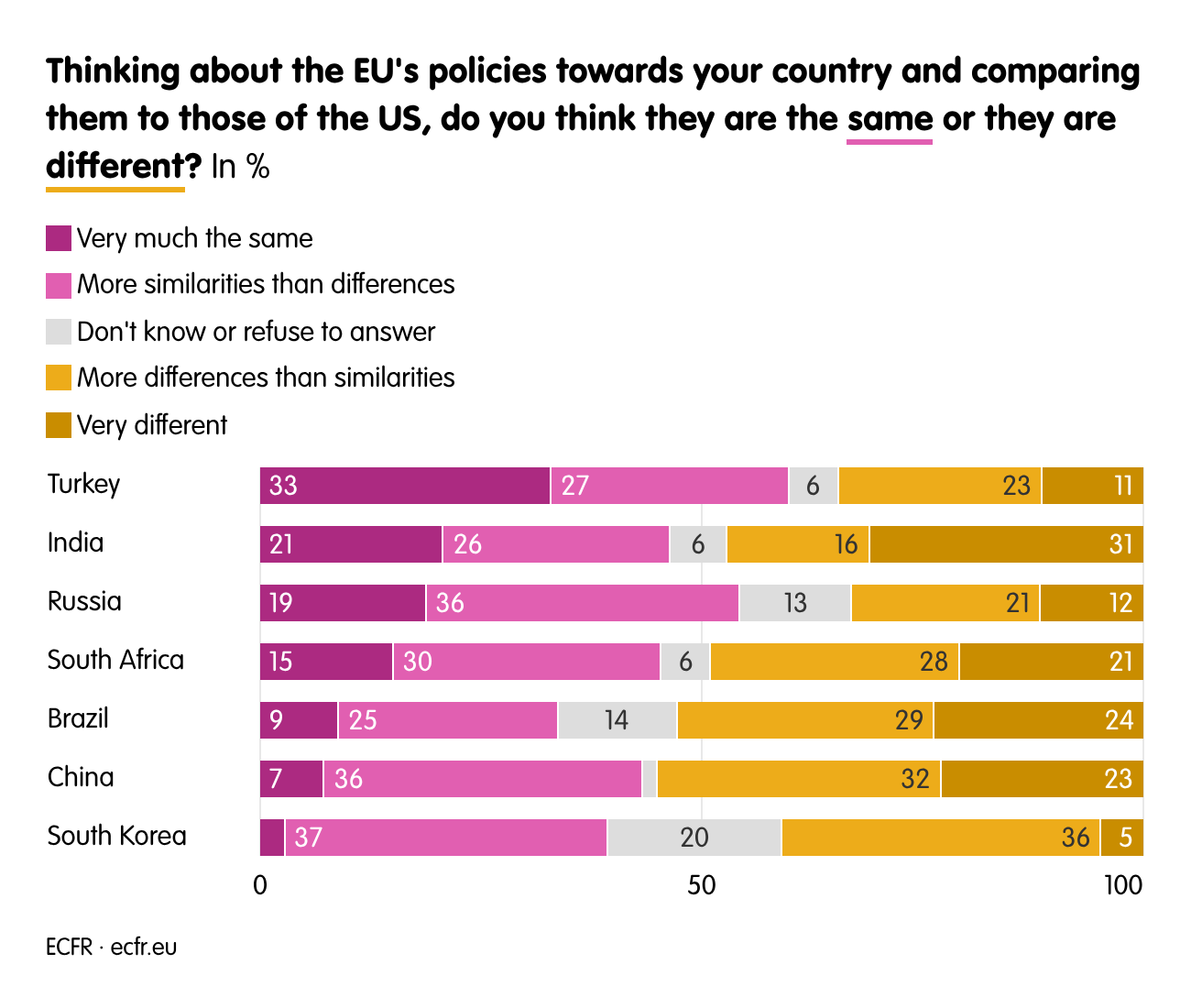

Chinese perceptions of Europe are also changing. When asked whether the EU’s policies vis-à-vis their country are similar or different from those of the US, most people in China think they are different. In the past, most Chinese held them to be similar. What is more, while the perception of the EU’s distinctiveness has also increased in some other places—including India, Turkey and South Africa—nowhere has it risen as much as in China. This makes it one of only two countries, along with Brazil, where most people agree the EU’s approach to their country is different from that of America.

Altogether, this is a remarkable change from our first global poll, conducted in late 2022 with the impact of the war in Ukraine still fresh and Biden in the White House. That poll found a largely united transatlantic West.

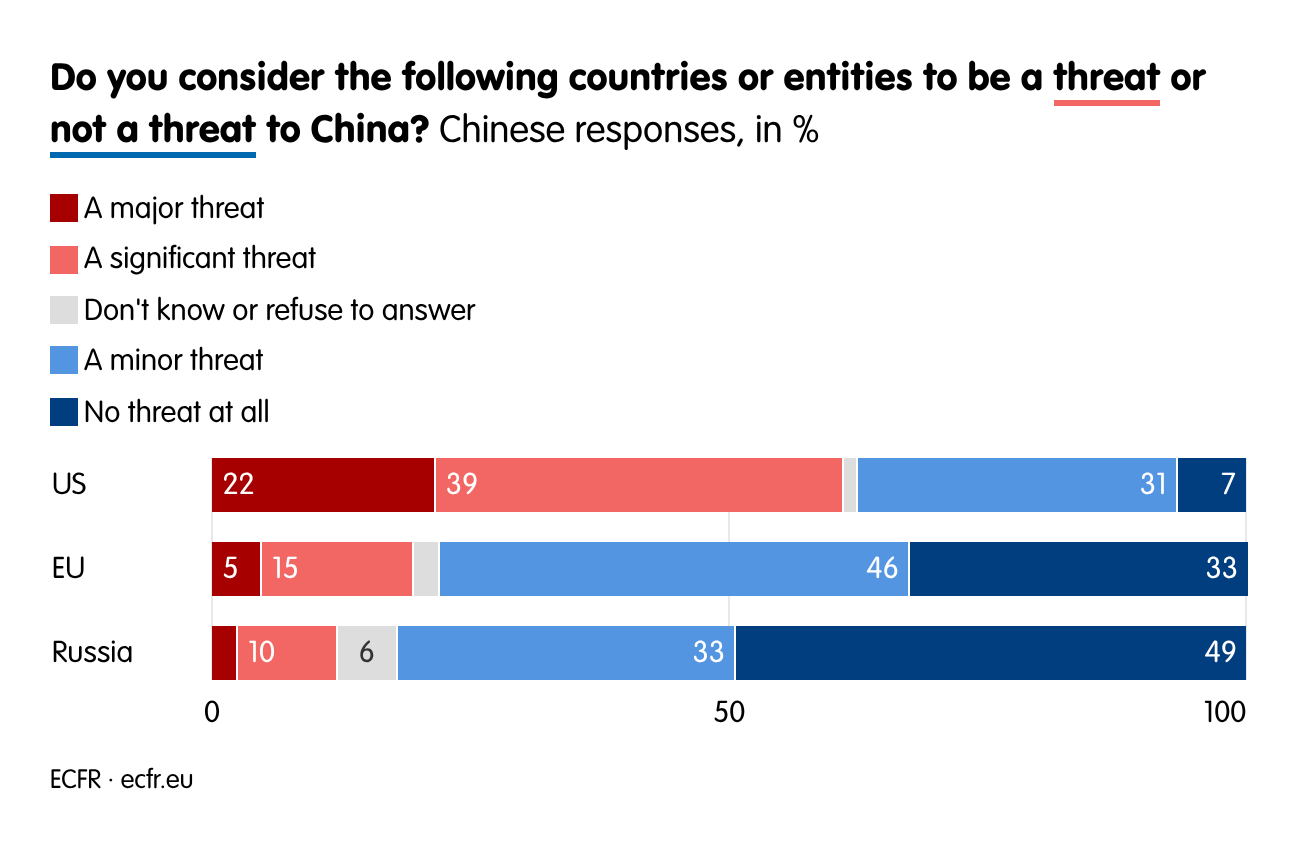

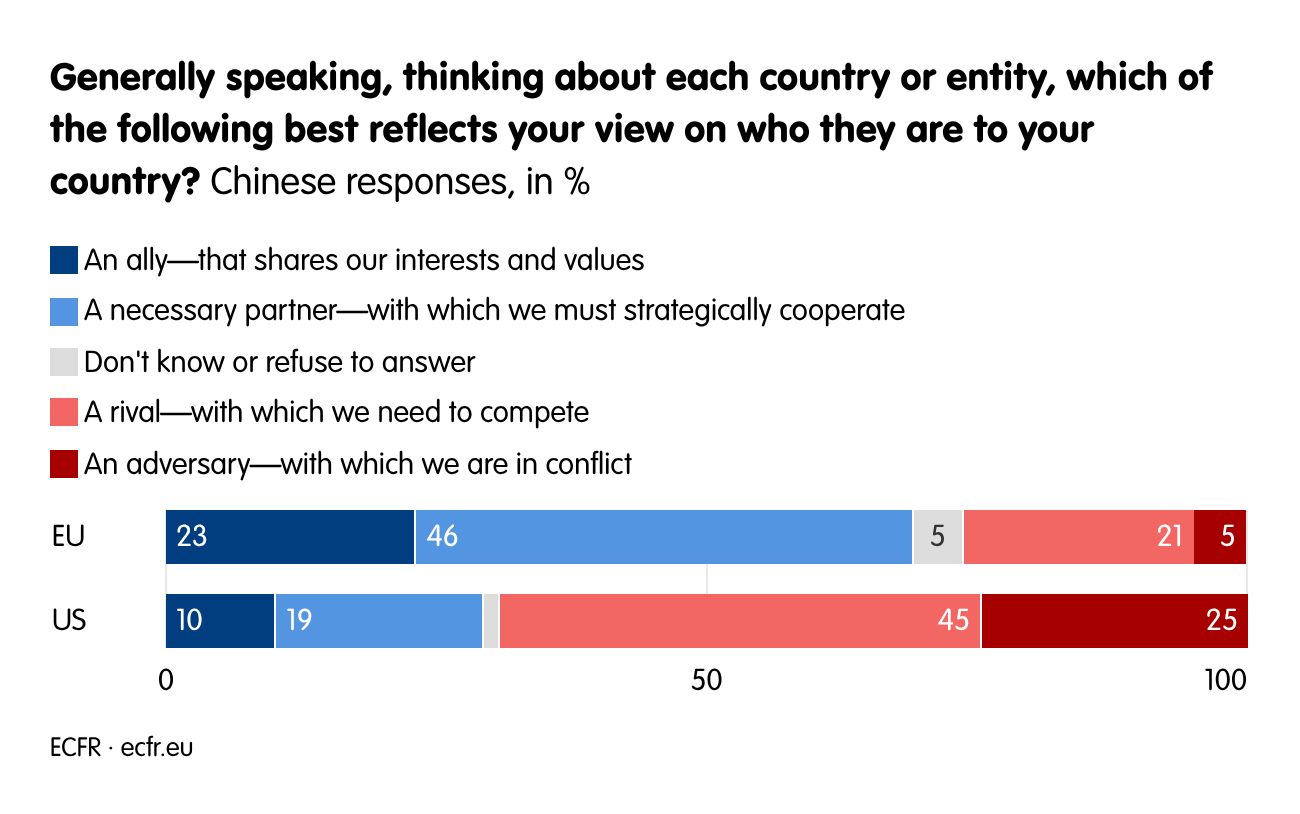

In keeping with this, while 61% of people in China see the US as a threat, only 19% think the same of the EU. This does not appear to be because Chinese citizens do not take the EU seriously: China is one of the few places where people regard the EU as a great power. This may therefore be because they view the bloc as a partner—as another pole in a multipolar world no longer dominated by America. While people in China consider the US chiefly a rival (45%), they consider the EU mostly a partner (46%).

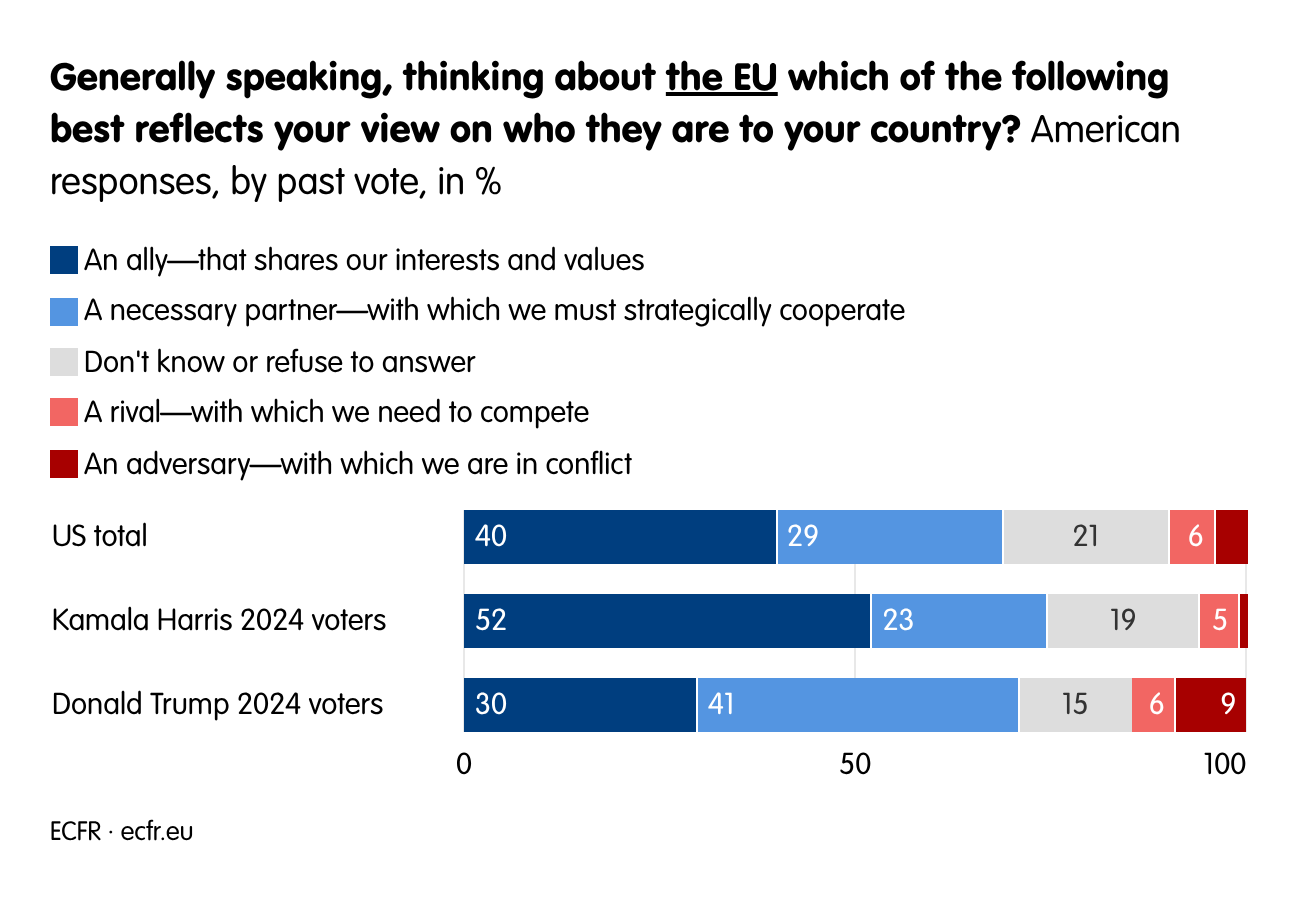

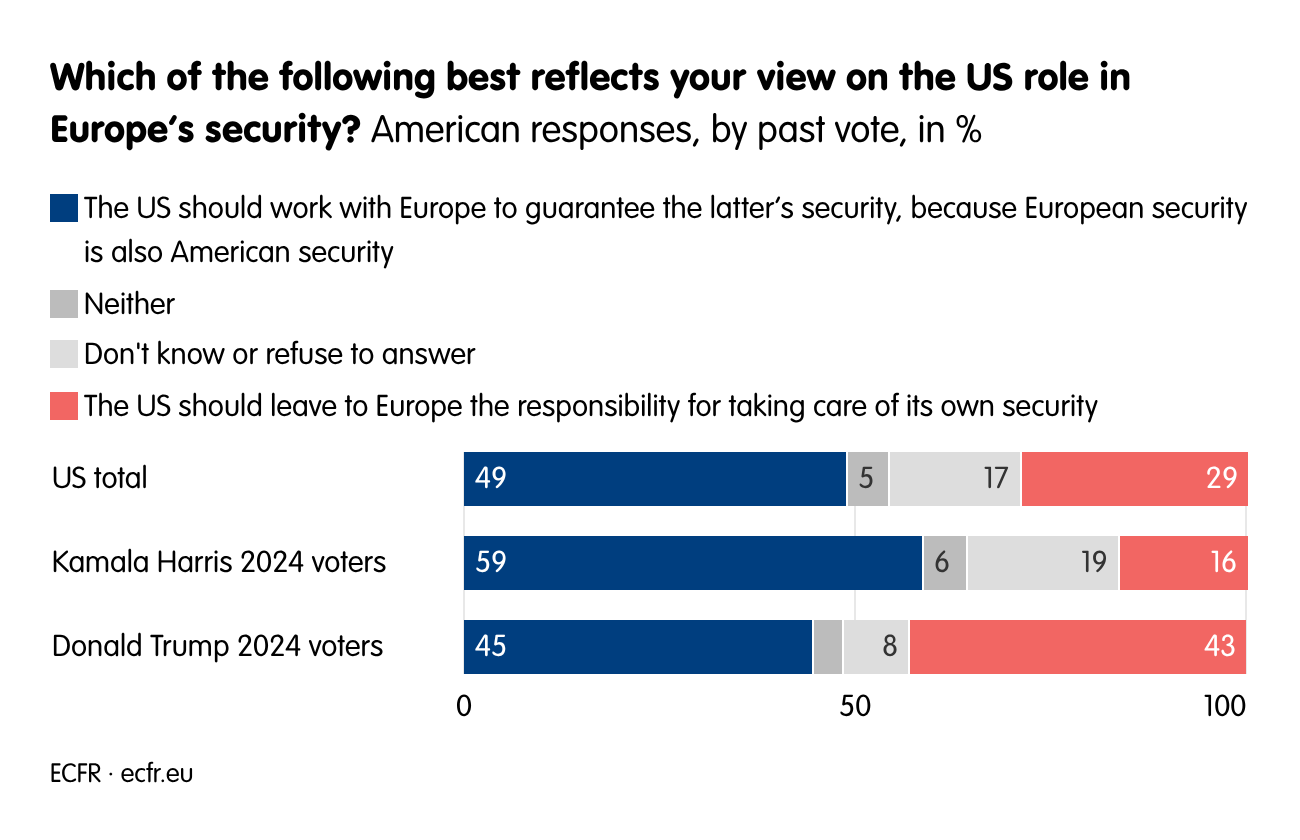

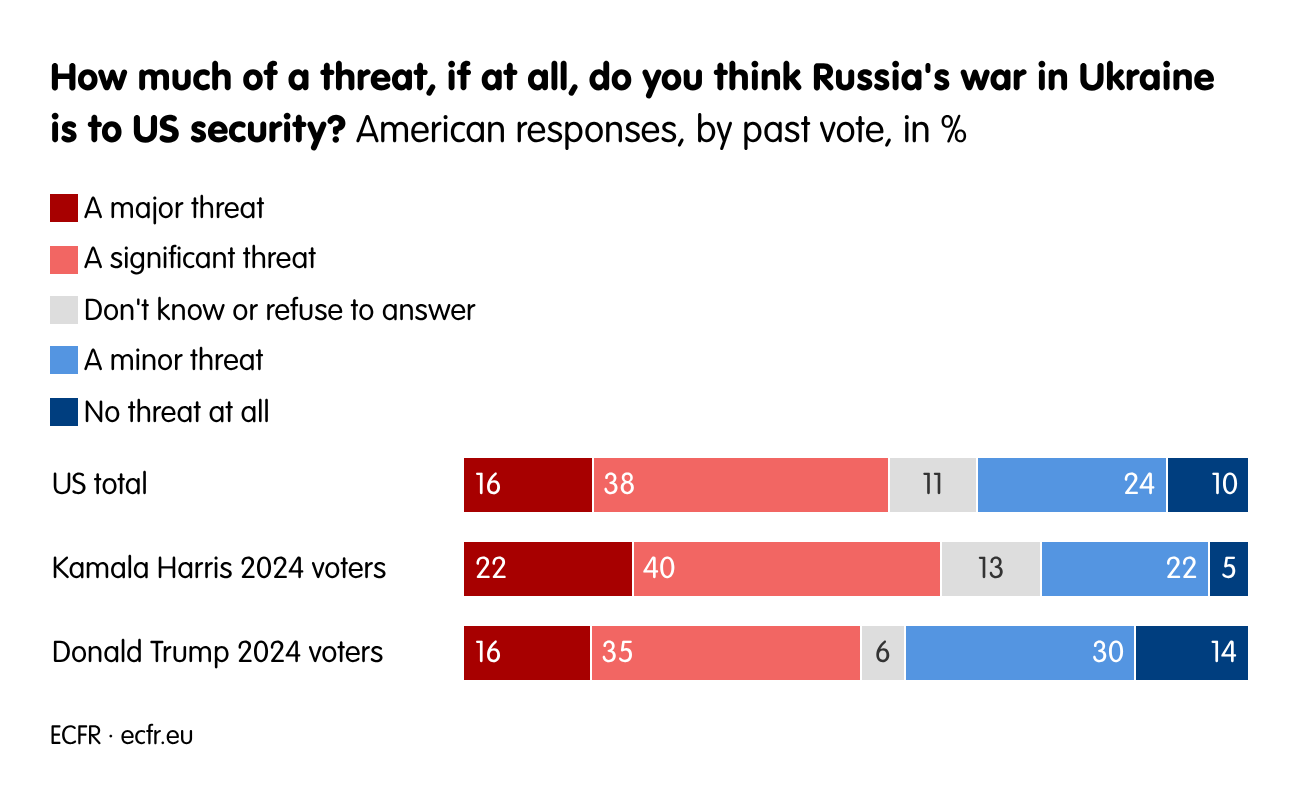

In contrast, Americans have not altered their views of the EU. And, whatever Trump might claim, his policies towards Europe and Russia do not represent a new American domestic consensus. The prevailing view in the US (40%) is to consider the EU an ally. Half of Americans (49%) subscribe to the view that “European security is also American security”; only 29% do not. And more than half (54%) of Americans consider Russia’s war in Ukraine a threat to American security.

Even more importantly, Republican and Democratic voters do not line up neatly behind positions against or in favour of the EU. If anything, Trump’s own electorate is internally divided over questions around Europe and Russia. But the transatlantic divide is even bigger, with only 25% of Britons and 16% of EU citizens now agreeing that the US is their ally.

How Europe sees itself in a post-Western world

What about Europeans themselves? Are they ready for a post-Western order with a “normal” America, superpower China and many countries embracing multipolarity? The findings suggest people in some parts of the world see great potential in Europe. But much remains for Europeans to embrace their own power, and they are starting from a gloomy place.

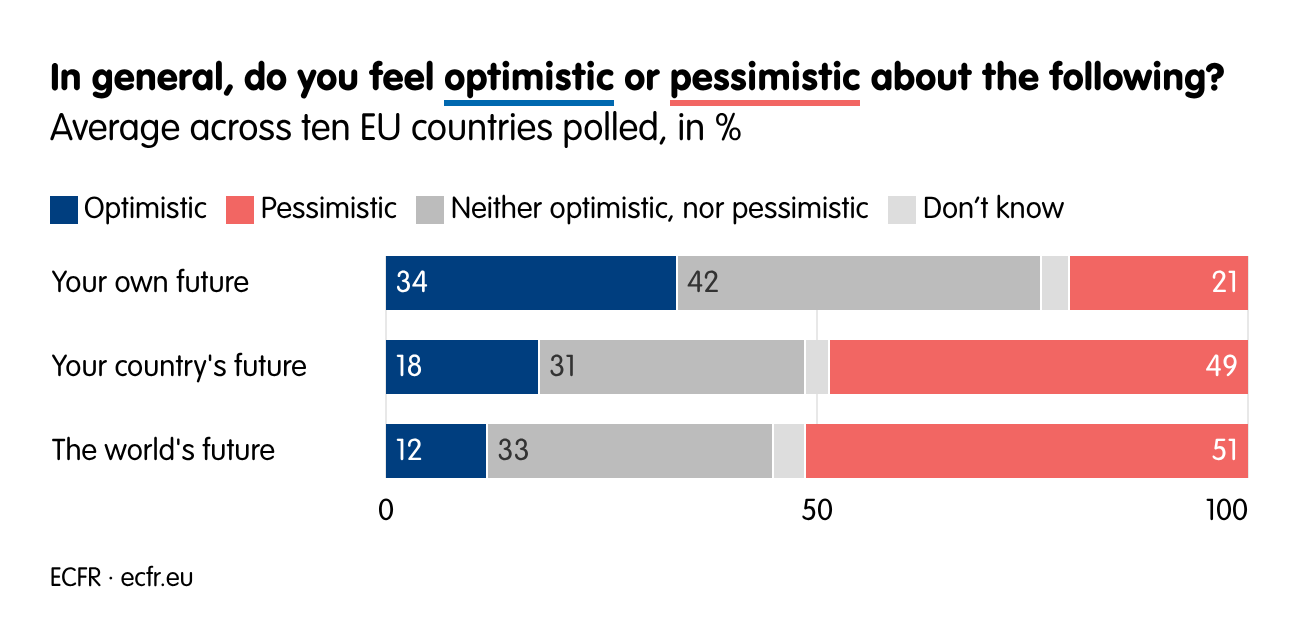

Many European citizens are conscious they are now living in a post-Western world, and see it as a risk rather than an opportunity. The data confirm that Europeans are among the chief pessimists in the world today. Most Europeans doubt the future will bring any good for their countries, the world or themselves individually. (The survey did not explore people’s optimism about the EU’s future, which—based on September 2025 Eurobarometer data—seems to be doing better, with 52% across EU27 feeling optimistic and 43% pessimistic.)

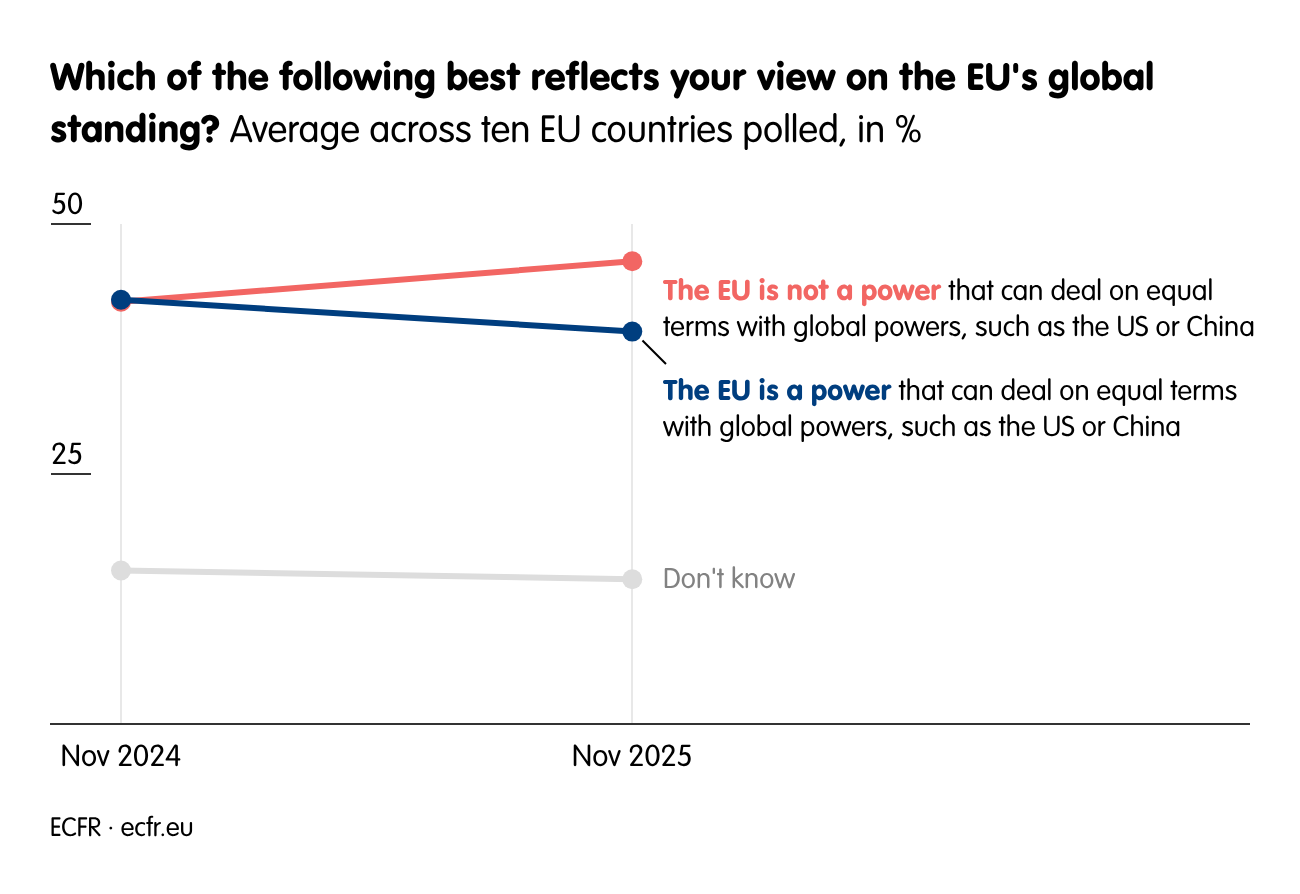

Most Europeans do not believe the EU is a power able to deal on equal terms with the US or China—and these doubts have grown over the past 12 months. As data presented earlier showed, Europeans are among the least confident in the EU’s strength. In contrast, most people in South Africa, Brazil, China and Ukraine say the EU is a force to be reckoned with. Trump’s and Putin’s aggressive and dismissive views of Europe might be among the chief factors shaping perceptions in Europe—especially since those views are echoed and magnified by an array of antiliberal, nationalist populist parties across the continent.

Europeans’ pessimism may also be a reaction to the mixed messages their leaders have been sending. European leaders are privately aware that the transatlantic relationship as it once existed is over. Nevertheless, they have spent most of the last year undertaking transatlantic damage control by flattering Trump and trying to pretend this is the alliance it was before.

On the surface, Europeans may already be making the mental shift to a post-Western world in which Europe increasingly finds itself alone. They harbour no illusions about the US under Trump. They support ramping up defence spending and realise they are living in a dangerous world.

More specifically, European opinion of the US and Trump has worsened. As noted above, fewer Europeans than a year ago believe Trump is good even for American citizens. Fewer Europeans also now think the US is an ally or partner.

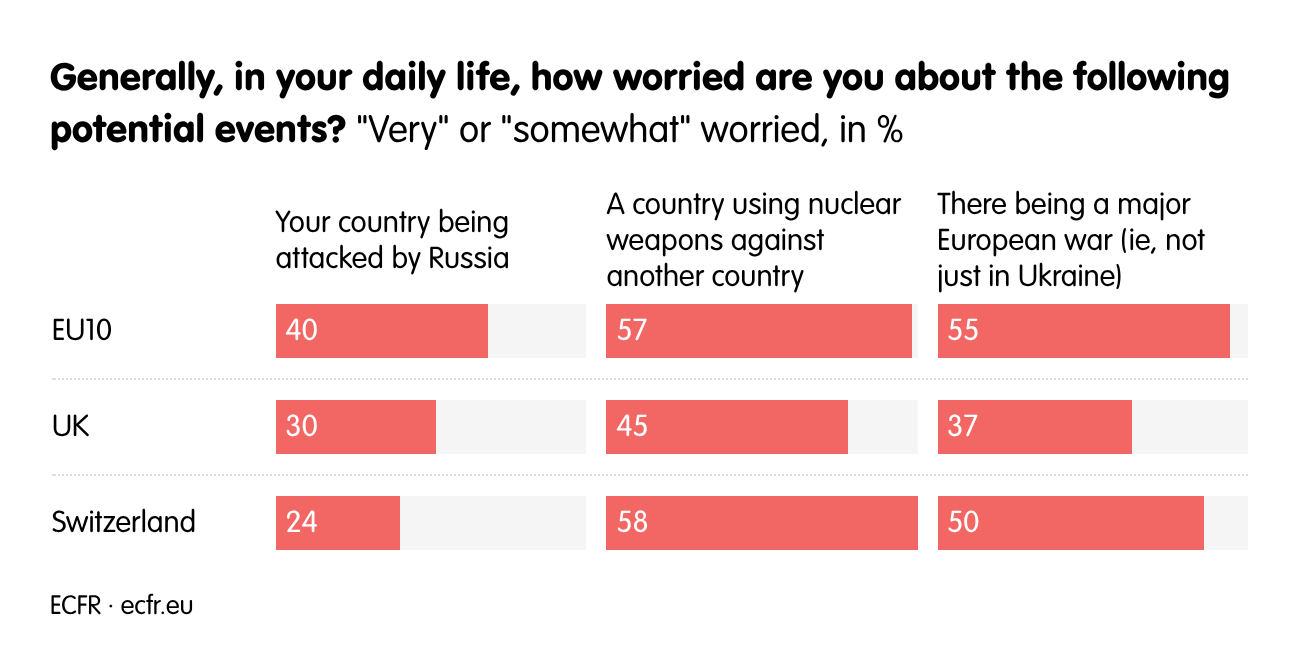

Many Europeans feel they are living through a perilous moment. They express high levels of worry about Russian aggression against another European country, the likelihood of a major European war and the use of nuclear weapons.

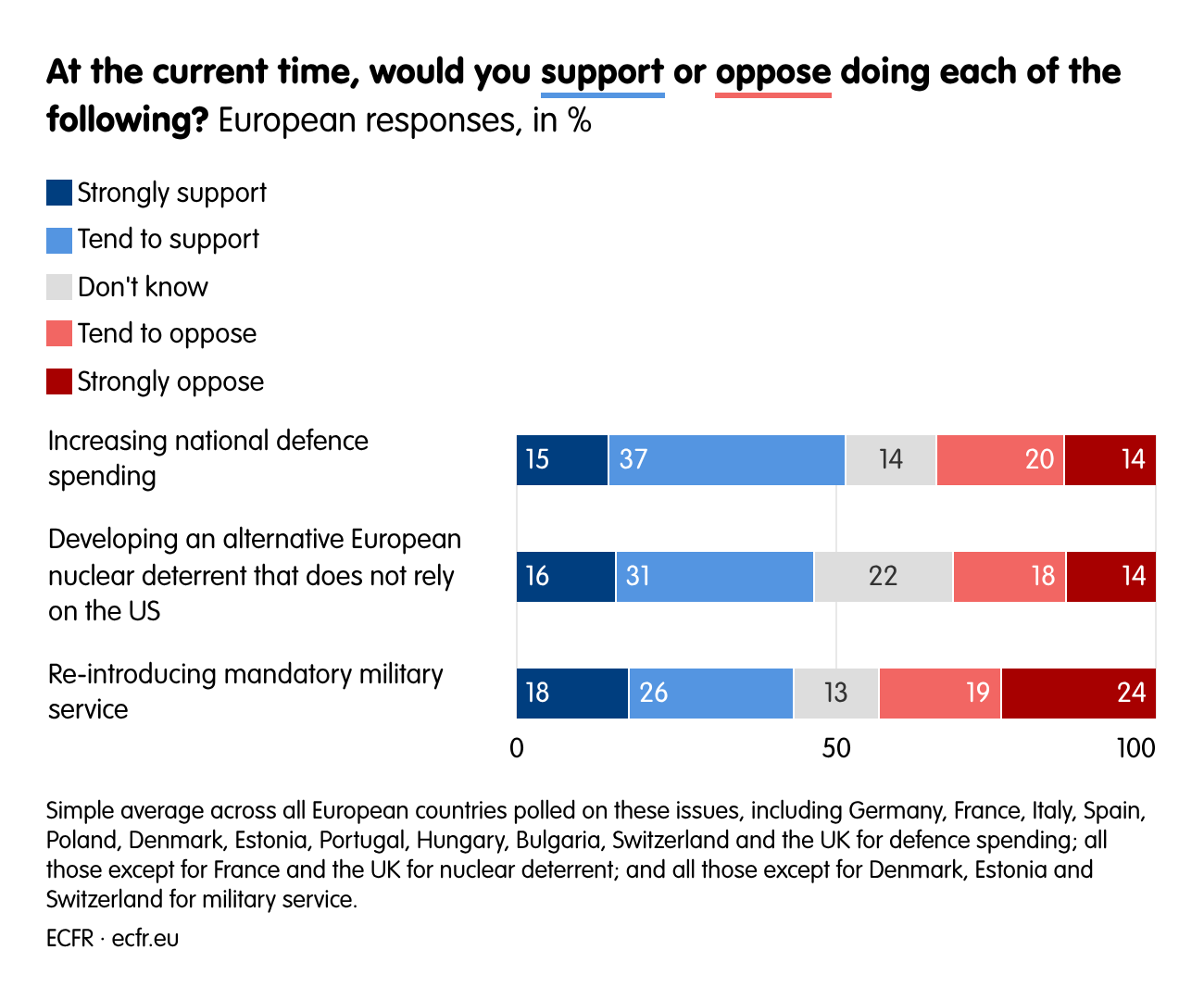

By the same token, support is strong across Europe for boosting defence spending, reintroducing mandatory conscription and even developing a European nuclear deterrent.

Politicians should understand that these various elements of Europe’s geopolitical awakening do not necessarily overlap in people’s minds. Political leaders are desperately trying to work out how to lead their countries in this dangerous world. But they are partly to blame for failing to tell a story about what the dramatic events of this year mean for Europeans. (ECFR will offer further insights into the views of the European public in a separate paper that will be published soon.)

Urgent questions for Europe

ECFR’s new poll reveals a world in which the actions of America—once Europeans’ staunchest ally—are helping “make China great again”, ushering in a truly multipolar world. Trump’s intervention in Venezuela indicates he has decided it is better for a great power to be feared than to be loved. And Europeans are coming to terms with the fact that even a once-close ally of the US like Denmark is threatened with the seizure of Greenland, almost as if a fellow NATO member were an enemy power.

In 2026 Europe could end up squeezed or simply ignored in such a world in flux, although mixed views of European power generate hope as well as trepidation. Indeed, the findings confirm an urgent sense of threat among Europeans, combined with deep uncertainty about how to respond when China is not only on the rise, but has risen. Political leaders in Europe should no longer ask themselves whether their own citizens grasp the radical nature of the current geopolitical changes. They do.

The crucial question now for leaders and voters is what Europe should look like in 2030 if it is to stand up for itself in all dimensions of power: military, economic, and cultural and political power. European publics appear to be well prepared for the message recently conveyed by Chancellor Friedrich Merz that the “Pax Americana” is over. The contrast with our first global poll is very striking. This was conducted just three years ago, when people saw a united transatlantic West standing up for Ukraine against Russia, on the one hand, and a broadly Russia-friendly “rest”, on the other. Even given the tactical necessity of flattering the boundless narcissism of Trump, more honesty at home about where Europe stands in this post-Western, “China first” world is essential to formulating a coherent European strategy.

During a period when both excessive pessimism and excessive optimism are counterproductive, European leaders should be realistic and daring at the same time. In an era of “changes unseen in a century”, they will need to find new ways not just to manage in a multipolar world, but to become a pole in this world—or disappear among the others.

Can Europe, on its own, ensure a secure, free and prosperous future for Ukraine? How can Europe avoid a “dirty peace” while not facing accusations from its own citizens of obstructing the path to peace? Does a politically divided continent have adequate policy coordination, power and political will to stand up militarily to Russia, economically to China and politically to the US (including in defence of Greenland)? Or should it embrace a policy of “neo-Habsburgian” pragmatism, aspiring simply to survive the current moment of maximum vulnerability? How realistic would it be for the EU to seek a closer relationship with China to compensate for weakening ties with the US while cheap Chinese exports threaten to destroy Europe’s industrial base? Is there any hope of creating a “new West” with like-minded powers such as Canada, Australia and Japan? These are the questions that Europeans urgently need to address in 2026.

Methodology

This report is based on a public opinion poll of adult populations (aged 18 and over) conducted in November 2025 in 15 European countries (Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and the United Kingdom) and six non-European countries (Brazil, China, India, South Africa, South Korea and the United States). The total number of respondents was 25,949.

In Russia, Turkey and all countries outside Europe the polls were conducted by Gallup International Foundation Institute through a network of independent local partners and cross-country panel operators as an online survey in: Brazil (1,000 respondents; 3-7 November; through Market Analysis Brazil); China (1,005; 7-14 November; through Distance/Dynata); Russia (1,000; 5-17 November; through Be Media Consultant); South Africa (1,007; 3-12 November; through Distance/Dynata); South Korea (1,000; 7-14 November; through Gallup Korea); Turkey (1,005; 7-12 November; through Distance/Dynata); and the US (1,016; 3-4 November; through Distance/Survey Monkey). The survey in India was conducted face to face (1,022; 10-19 November; through Convergent). The face-to-face method was preferred there, taking into consideration the insufficient coverage and internet quality in some of India’s smaller cities.

In Brazil, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey and the US, the sample was nationally representative for the adult population by basic demographics. In China, the poll included panellists only from the country’s four biggest agglomerations: Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai and Shenzhen. In India, rural areas and tier-3 cities were not covered. And in Russia, only cities of at least 100,000 inhabitants were covered. Therefore, data from China, India and Russia should be considered as representative exclusively for the population covered by the polls. Moreover, the politically sensitive character of several questions means that the results from China and Russia need to be interpreted with caution because of the possibility that some respondents might have felt constrained in expressing their opinions freely.

In the remaining European countries, the polls were conducted online by Datapraxis and YouGov in Bulgaria (1,020; 5-21 November); Denmark (1,029; 5-13 November); France (1,518; 5-18 November); Germany (2,028; 5-14 November); Hungary (1,020; 5-14 November); Italy (1,501; 5-19 November); Poland (1,525; 5-14 November); Portugal (1,030; 5-17 November); Spain (1,566; 5-13 November); Switzerland (1,104; 5-14 November), and the UK (2,034; 5-15 November). Polls were conducted by Datapraxis and Norstat in Estonia (1,018; 7-19 November). In Ukraine, polls were conducted by Datapraxis and Rating Group in Ukraine (1,501; 8-11 November) via telephone interviews (CATI), with respondents selected using randomly generated telephone numbers. The data were then weighted to basic demographics. Fully accounting for the population changes due to the war is difficult, but adjustments were made to account for the territory under Russian occupation. This, combined with the probability-based sampling approach, strengthens the level of representativeness of the survey and generally reflects the attitudes of the Ukrainian public in wartime conditions.

In this policy brief, and unless stated otherwise, the results for “the EU” correspond to a simple average across ten EU member states within the sample (ie, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, and Spain).

About the authors

Timothy Garton Ash is professor emeritus of European studies at the University of Oxford and a founding member of ECFR. His most recent book is “Homelands: A Personal History of Europe”.

Ivan Krastev is chair of the Centre for Liberal Strategies, Sofia, and a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences, Vienna. He is the author of “Is It Tomorrow Yet?: Paradoxes of the Pandemic”, among many other publications.

Mark Leonard is co-founder and director of the European Council on Foreign Relations. He is the author of “The Age of Unpeace: How Connectivity Causes Conflict”. He also presents ECFR’s weekly “World in 30 Minutes” podcast.

Acknowledgments

This polling and analysis were the result of a collaboration between ECFR and the “Europe in a Changing World” project of the Dahrendorf Programme at St Antony’s College, University of Oxford. ECFR partnered with the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Switzerland’s Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, International Center for Defence and Security and Think Tank Europa on this project.

[1] Author conversation with a Russian analyst, 2025.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.