The House of Lords is set to vote on proposals for a ban next week, which could see an amendment added to the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill.

Many Labour MPs and officials have said they expect the UK government to follow Australia’s example, with several other European nations weighing similar laws.

Health Secretary Wes Streeting this week indicated was in favour of a ban, while Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch has said she would bring one in if her party won the next election.

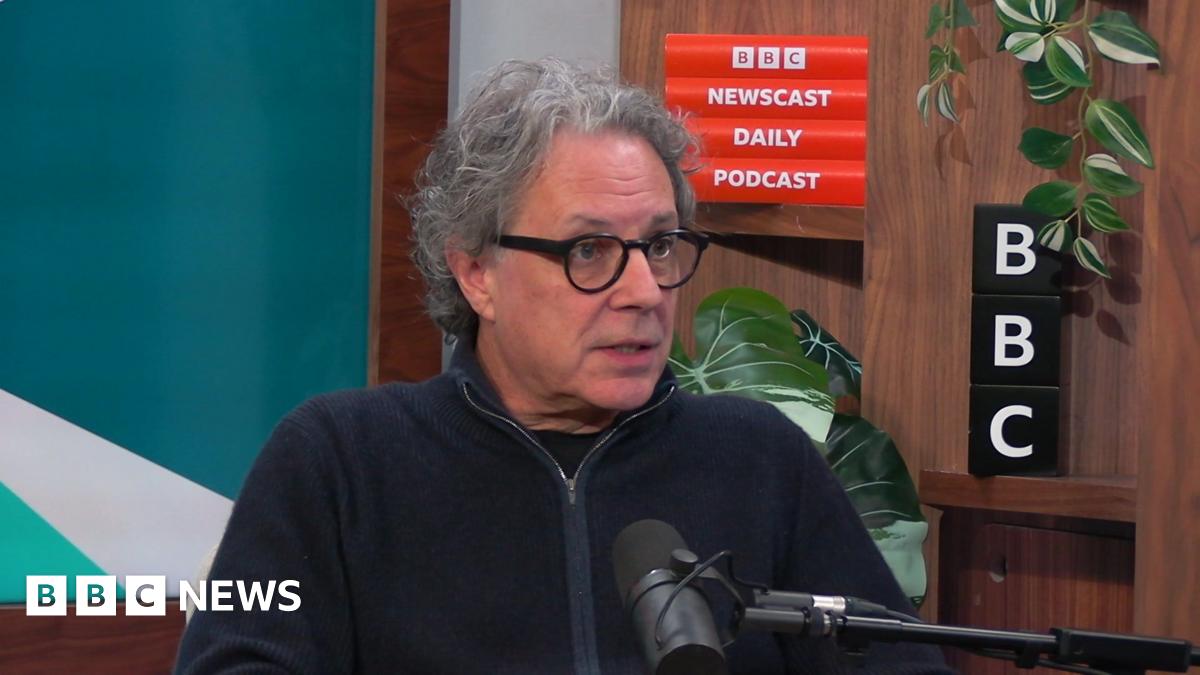

But Ian Russell – who has campaigned for better online protections for children since his daughter took her own life in 2017 aged 14 – says bereaved families are “horrified” at the way politicians had capitalised on the issue.

“Many of them have said things like: ‘this is not something that should be a party political issue’.”

The government should instead be enforcing laws already on the books more robustly, he argued.

Russell expressed concerns about the “unintended consequences” of a ban, which he said would “cause more problems”.

“At the heart of it are companies that put profit over safety,” he said. “That has got to change – and I don’t think that we’re that far away from it changing it – which is why its slightly exasperating that we’re going through these same arguments again now about bans.

“It’s not far away – we can build on what we’ve got far better than simply implementing sledgehammer techniques like bans that will have unintended consequences and cause more problems.”

The Molly Rose Foundation, a suicide prevention charity named after his daughter, and organisations including the NSPCC and Childnet, called a ban the “wrong solution”.

“It would create a false sense of safety that would see children – but also the threats to them – migrate to other areas online,” they wrote in a joint statement, external.

“Though well-intentioned, blanket bans on social media would fail to deliver the improvement in children’s safety and wellbeing that they so urgently need.”

Instead of this “blunt response”, the statement – which was also signed by two child mental health practitioners – called for a “broader and more targeted” approach.

Existing law should be “robustly enforced” to ensure social media sites, games and AI chatbots were not accessible to under-13s, it said, while all social media platforms should have evidence-based blocks for features that are considered risky for children of different ages.

The statement urged the government to strengthen the Online Safety Act to compel online companies to “deliver age-appropriate experiences”.

It suggested: “Just as films and video games have different ratings reflecting the risk they pose to children, social media platforms have different levels of risk too and their minimum age limits should reflect this.”