After the shakedown in Barcelona, the first question to ask is whether it really had to be so secretive. Of course, it matters that ‘official’ winter testing is organised in Bahrain and that, for commercial reasons, only that event is allowed to carry that name, but fears of a repeat of 2014 have proven unfounded.

Williams was absent, Audi ran into some teething troubles as a newcomer, and yes, there were red flags, but that’s entirely normal at the start of a new era. It has certainly not been a catastrophe. In fact, the opposite can be argued: it is praiseworthy that most teams have come out of the blocks so productively after a very short winter break and the biggest technical overhaul in decades.

The fact that the shakedown was held behind closed doors does mean that only a limited number of images emerged, and in a highly orchestrated manner. Teams and F1 could share exactly what they wanted, which means that for a more complete picture we have to wait for Bahrain.

There is also the disclaimer that always applies in pre-season: these are only the first versions of the new cars, and countless developments will follow ahead of the season-opener. Especially under these new regulations, the rate of development will be incredibly high, meaning this ‘base package’ does not tell the whole story by any means.

Nevertheless, first impressions are always interesting. In the build-up to 2026, several technical directors said the new regulations would be fairly rigid and offer little freedom, but Adrian Newey somewhat revised that view last year: “It’s exactly the same [as in 2022].

“When I first looked at the 2026 rules, my first reaction was, God, this doesn’t leave much. But then you start to drill into the detail and there is a reasonable amount of flexibility. Of course, I’d always like more, but there’s a reasonable amount of flexibility.”

The first images of the 2026 cars confirm those words, not least thanks to Newey’s creation. Although the overall concepts may not look radically different at first glance, those differences do become very clear when looking a bit closer.

Front wing – Playing with active aero and outwash?

The FIA has paid a lot of attention to front wings to limit outwash, but F1 teams still have considerable design freedom. That is already visible in some differences between teams in their active aerodynamics choices.

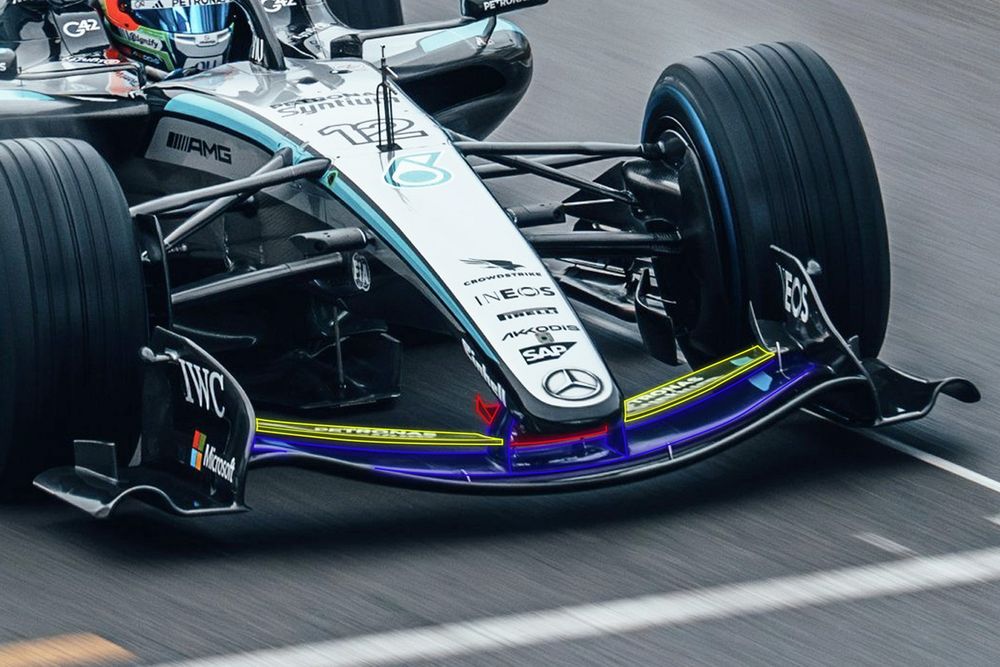

Most teams have mounted the nose to the main element of the front wing, allowing the second and third elements – as the regulations permit – to flatten on the straights. Aston Martin and Mercedes, however, ran a different configuration in Barcelona. Both teams had the nose pylons attached to the second element, meaning only the upper element remained free to move as active aerodynamics. According to the regulations, both elements may move: one by 60mm and the other by 30mm.

By attaching the nose to the second element, those teams theoretically sacrifice some of that freedom, but even if that is the case, there may be several reasons behind it. First of all, it allows the structural part of the nose to be slightly shorter than most rivals’, where the second element flattens out. Secondly, attaching to the second element seemingly offers more design freedom for the main plane, which can be seen in the profile of the Aston Martin wing.

Teams have also hinted that their active aero choices are closely linked to the amount of downforce required per track. It is not a given that this will actually be the design used in Melbourne, let alone the rest of the season. Last year, several teams could adjust the nose without having to undergo another crash test, which in theory leaves more room to play with exactly these aspects.

The front of the Mercedes W17, clearly showing that the nose rests on the second wing element

Another detail is that some teams have a small opening in the nose. On the Mercedes, this hole can be seen between the Akkodis and SAP logos. It provides access to a flap adjustment mechanism, for example during pitstops. With this system, adjustments happen on both sides, whereas in the old-fashioned way – outboard on the wing – both sides had to be adjusted manually. A similar hole can also be seen on the Red Bull and McLaren, while the Ferrari SF-26 does not have it at this stage.

There are also initial differences in wing designs. All teams have a fairly standard vortex tunnel on both sides, albeit with quite some variation, and there are even more visible differences in how teams try to generate outwash – linked to the disturbance factor of the front tyres. As mentioned, that is not the FIA’s intention, but a comparison of all front wings clearly shows that teams are trying to exploit as much as possible within the margins they’ve been given.

Most teams – as seen on the new McLaren – have added a fairly horizontal fin to the wing endplate. If disturbed air from the tyres moves inwards, it disrupts airflow to the floor and the rest of the car. Teams try to send it outwards as much as possible, which those fins are partly responsible for – McLaren’s fin also points downwards, creating a modest downwash effect along the way.

Front suspension – Predominantly pushrod, but with extreme designs

At Aston Martin, such a fin was not yet visible during the first laps at Catalunya, but Newey’s creation looks extreme in many other ways. That applies, for example, to the relatively wide nose that then tapers – another area where the 2026 cars differ considerably so far.

Exactly the same can be said when looking at the front suspension. There is a clear general trend: most teams have returned to a pushrod front suspension. Under the previous regulations, a pullrod at the front became by far the more popular solution, with Red Bull and McLaren as trendsetters.

Pushrod and pullrod suspensions have their pros and cons. With a pullrod, the inboard suspension elements sit lower, slightly lowering the centre of gravity. With a pushrod, those components sit higher, making them more accessible for mechanics and therefore easier to work on.

In addition, as James Key recently explained, a pushrod can theoretically be slightly lighter – which, given the rather ambitious minimum weight for 2026, may be a welcome side effect for some teams. The choice between pushrod and pullrod, however, mainly has aerodynamic consequences, and those have ultimately been decisive.

Under the previous regulations, most teams considered the pullrod better suited to guide airflow as optimally as possible towards the floor tunnels. But with the new rules relying much less on ground effect, that trade-off has changed in interaction with the new front wing. Only Alpine and Cadillac are currently opting for a pullrod front suspension, and it is noteworthy that the Enstone team tried to suggest exactly the opposite at its launch.

The pushrod front suspension of the McLaren MCL40, with considerable anti-dive

Beyond that choice, teams are playing with anti-dive to varying degrees. McLaren was already known for this last year, as it went quite extreme – and that is no different this year. It can be seen in the height difference between the forward pickup point and the rear leg, and McLaren is clearly not alone in this.

Based on the first images of the new Aston Martin, Newey’s creation takes this to an even greater extreme. The front leg’s mount point is placed as high as possible, while the rear leg sits as low as possible. This not only creates the aforementioned anti-dive but also affects the airflow towards the lower areas of the car – which, knowing Newey, has likely been another key consideration.

Sidepods – Initial variation across the grid

Further back, something resembling the bargeboards from previous F1 eras has returned, although this time the FIA has a completely different function in mind with the side deflector arrays – or wakeboards. Whereas teams previously used these elements primarily to generate outwash, the governing body now wants to use them in an attempt to minimize dirty air.

For that reason, they were intended as inwash devices, although the first images clearly show that teams are trying to prevent that as much as possible. In this area too – both in the panel arrangement and shaping – teams have opted for different solutions, although the Bahrain test days will provide a better overview. It will be interesting to hear what the FIA thinks of some of the most obvious attempts to create more outwash, as that was not the intention of their 2026 plans.

We then come to the aspect that – together with the front wing and front suspension – visibly stands out the most: the sidepods. On Thursday, all attention was on the AMR26 when it was finally rolled out late in the afternoon. Also here, Newey has gone for an aggressive design. The downwash sidepods (a broad trend, albeit in various forms) are extremely tightly packaged, to the extent that there seems little volume for radiators, resulting in a substantial undercut.

Newey’s AMR26, with the nose on the second wing element, aggressive sidepods with underbite inlet, and horns next to the airbox

Notably, Newey has opted for a so-called underbite inlet. This is not a surprise, as Newey did the same in the previous era at Red Bull. The trend later shifted towards overbite, led by McLaren’s influence, although Newey was not a fan of it himself.

The overall shaping towards the rear is very compact as well, which also helps reduce drag. Under the new regulations, it’s an important factor, given the energy management and drag reduction already required to make the new engine formula work. It would therefore not be surprising if Newey had placed more emphasis on that.

As for the sidepods – beyond the undercut and downwash philosophy that many teams have adopted – Red Bull and Alpine stand out in different ways. Red Bull opted for a very compact design in Barcelona. On social media it was quickly linked to zero-pod, but a view from the front makes clear that this is definitely not the case – with a sidepod wing including the upper element of the Side Impact Structure.

Further back, the Red Bull sidepods taper off extremely tightly, creating enormous space for the airflow over the floor edges towards the rear and the diffuser area.

Alpine has seemingly gone the opposite route: very wide sidepods that leave little of the floor edges exposed from above, and a waterslide. As the previous period has shown, convergence in this area is very possible or even likely over time, but it is interesting that there is again some variation to start with.

Engine cover, bodywork solutions and slotted diffuser

Regarding the airbox and engine cover, there are also differences to notice. Interestingly, the Aston Martin appears to feature some Ferrari characteristics from recent years. In the first photos, a triangular airbox with side horns can be seen. Those horns, along with the vents on the engine cover and the overall shape, resemble what Ferrari has used in recent years.

The compact, triangular airbox of the Ferrari SF-26

This is not a surprise, as technical director Enrico Cardile has moved from Maranello to the Silverstone-based outfit, making it logical that alongside ‘Newey traits’ there are also some ‘Cardile traits’ on this year’s car – and those seem particularly evident around the engine cover.

As for the airbox, Racing Bulls has by far the largest on the grid, contrasted by their narrow sidepod inlets. Notably, Red Bull’s airbox, despite using the same power unit, is already more compact. Ferrari, as in recent years, has gone a step further with a compact triangular version, unlike the rounder shapes still seen on most Mercedes-powered teams. Both Red Bull and Ferrari have a fairly pronounced shark fin thanks to relatively slim engine covers, although Ferrari’s – like McLaren’s – is stepped, while Red Bull’s currently is not.

At the rear of the car, teams always try to keep their cards close to their chest, and that’s no different with the images that were shared during the Barcelona test. Good photos of the rear suspension are not yet available from every team, meaning we have to wait for a better overview in Bahrain.

However, the first images show that Aston Martin has positioned the top wishbone extremely high, especially the rear leg, which is consistent with its philosophy at the front of the car. Moreover, the green team seems to have opted for above-average rake, which, given some of Newey’s previous creations, should not come as a major surprise either.

Finally, the diffuser received a lot of attention over the past week, as the flatter floors generate significantly less downforce than in the ground-effect era. It makes extracting maximum performance from the diffuser an interesting task for teams. Under the previous ruleset, it was crucial to completely seal the diffuser. Teams could use the strong airflow from the Venturi tunnels for the diffuser; sealing it was important to create as large a pressure difference as possible.

The hole in the diffuser is clearly visible at Mercedes, under the Petronas advertising on the sidepod

This year, reality is different. Because the FIA has simplified the floors, that airflow is no longer strong enough to achieve the same effect. This explains why teams have looked for other ways to strengthen the airflow towards the diffuser and thus generate as much downforce as possible in that area.

In the first images of the Mercedes, a popular solution became visible: an opening in the diffuser wall that works together with the undercut sidepods that guide airflow over the floor edges. Through such an opening, some teams are trying to use that airflow to help diffuser performance, as put simply, the stronger the airflow directed towards the diffuser, the more downforce can be generated.

After Mercedes, this opening was also seen on the Ferrari, Aston Martin and Red Bull cars, with the latter team seemingly taking it to quite an extreme. On McLaren’s MCL40, this mouse hole – as it has been called in the past – for a slotted diffuser was not yet visible based on the first images from Barcelona.

But as always at this stage, teams will undoubtedly introduce further developments ahead of Bahrain and Australia. Or as McLaren’s Neil Houldey summed it up on Friday night: “We’ve got lots and lots of pictures of everyone else’s cars. And again, it’s just useful to have that, to see what other people have been up to.”

And that is exactly the game now beginning for all 11 teams.

We want to hear from you!

Let us know what you would like to see from us in the future.

– The Autosport.com Team