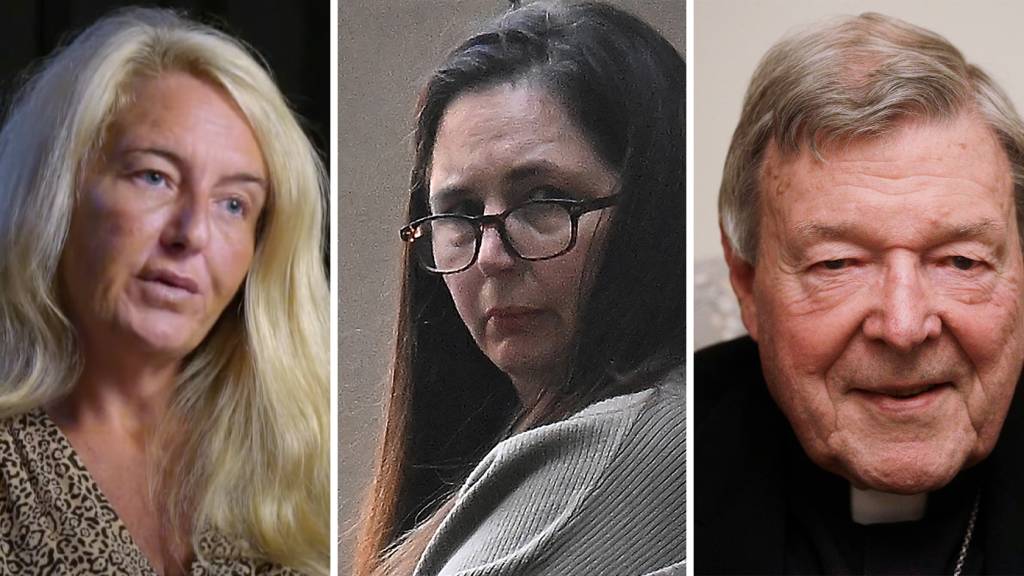

Over the weekend it was revealed that convicted murderer Erin Patterson had been accused by police of several attempts — also via poisoned food — on her husband Simon’s life.

Patterson, alongside the charges that would she was found guilty of — the murders of Simon Patterson’s parents Don and Gail Patterson and Gail’s sister Heather Wilkinson, as well as the attempted murder of Heather’s husband Ian — had pleaded not guilty to attempting to poison Simon several times over 2021 and 2022 via penne, Korma and a vegetable wrap.

The charges were eventually withdrawn and the details, never shared with the jury, were under a suppression order until Friday, when an interim suppression order prohibiting Australian media from reporting on any evidentiary rulings made in pre-trial hearings (and during the trial) was lifted after a coalition of media organisations successfully challenged the order.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1213255

Suppression orders are a common part of court proceedings, preventing the media from publishing details that could compromise a defendant’s chance at a fair trial. Victorian courts have long had a reputation for being the most generous in granting such orders, earning the state the title of the suppression order capital of Australia. In 2017, for example, Victorian courts issued 444 orders — twice as many as NSW, which had the next most.

As a result, the following major stories took a little longer to make it into the public domain.

Independent. Irreverent. In your inbox

Get the headlines they don’t want you to read. Sign up to Crikey’s free newsletters for fearless reporting, sharp analysis, and a touch of chaos

By continuing, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

Gangland

In 2007, Carl Williams, the “baby-faced killer” who had worked his way up the ladder of Australia’s criminal underworld via, among other things, a gangland killing spree, pleaded guilty to three murders, which allowed the media to publish previously suppressed charges about Williams. As it turned out, he was already in jail, serving 21 years for another murder which he’d been convicted of in July 2006.

Similarly, the rap sheet for former drug kingpin Tony Mokbel was subject to a series of blanket suppression orders. Information about a murder acquittal in 2009 was suppressed until 2011, when he pleaded guilty to a raft of drug trafficking charges.

The gangland suppression order flurry had surreal moments — Mokbel’s trial judge in 2010 not only suppressed any new reporting on proceedings against Mokbel or prior convictions, but also issued an order that specified outlets remove all historical online news articles containing any reference to Mokbel. This was later overturned by the Court of Appeal.

Further, in 2008 a Melbourne pub faced contempt of court proceedings for screening an interstate broadcast of Underbelly — Channel Nine’s dramatisation of Melbourne’s gang war. Screening the show was prohibited in Victoria by a suppression order, just days before the first episode was set to air, as former boxer Evangelos Goussis was about to stand trial for murder. Following his conviction, the show aired in Victoria, albeit heavily edited.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1209393

That didn’t stop hundreds, probably thousands, of Melburnians from instantly downloading the show from torrenting websites.

Lawyer X

Another key detail of the Melbourne gangland saga hidden under the veil of a suppression order was the identity of “Informer 3838” or “Lawyer X”. X, later revealed to be Nicola Gobbo after a suppression order was lifted, was a criminal lawyer who acted for gangland criminals such as Mokbel, and had been a registered police informer from 2005 to 2009.

Law Professor Jeremy Gans wrote at the time:

Amidst the many ramifications of the scandal, I hope that Victoria’s courts will themselves reflect on [the] indirect roles they played in these events … throughout the aftermath of Melbourne’s gangland war, Victoria’s courts imposed extensive suppression orders that, while well-intentioned, have largely prevented the public from gaining a full understanding of the methods used by Victoria Police in response.

Convictions secured via evidence provided by Gobbo were soon being overturned.

Even prior to the public revelations regarding X, her identity was the worst-kept secret in Victorian legal circles. And Gobbo knew it: “A Google search of my name is quite literally sickening, let alone googling ‘Lawyer X scandal’,” she wrote in a 2015 letter to police.

George Pell

The above cases point to the absurdity of suppression orders in the internet age. But the peak of that futility — as well as clashes between the media and the judiciary over suppression orders — came in 2018 and 2019, during the trials of cardinal George Pell.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1208941

Pell was convicted of child sex abuse in December 2018, but, as he was still to face another trial on the same charge, Australian outlets were gagged from reporting it. In response, media outlets went about heavily hinting at what was happening.

The Herald Sun published the headline “CENSORED” across a black front page, reporting that “The world is reading a very important story that is relevant to Victorians.” Indeed, local outlets could not tell their readers what a quick Google search or a visit to an international news site could.

As a result of this agitation over the trial, more than 100 journalists (including some at Crikey) were threatened with contempt proceedings, and several publications eventually had to pay a total of $1 million in fines. When the charges from the second trial were dropped, so was the suppression order, and Australia’s media went to town. In 2020, Pell’s convictions were quashed on appeal.

Which notable suppression orders have we missed?

We want to hear from you. Write to us at letters@crikey.com.au to be published in Crikey. Please include your full name. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.