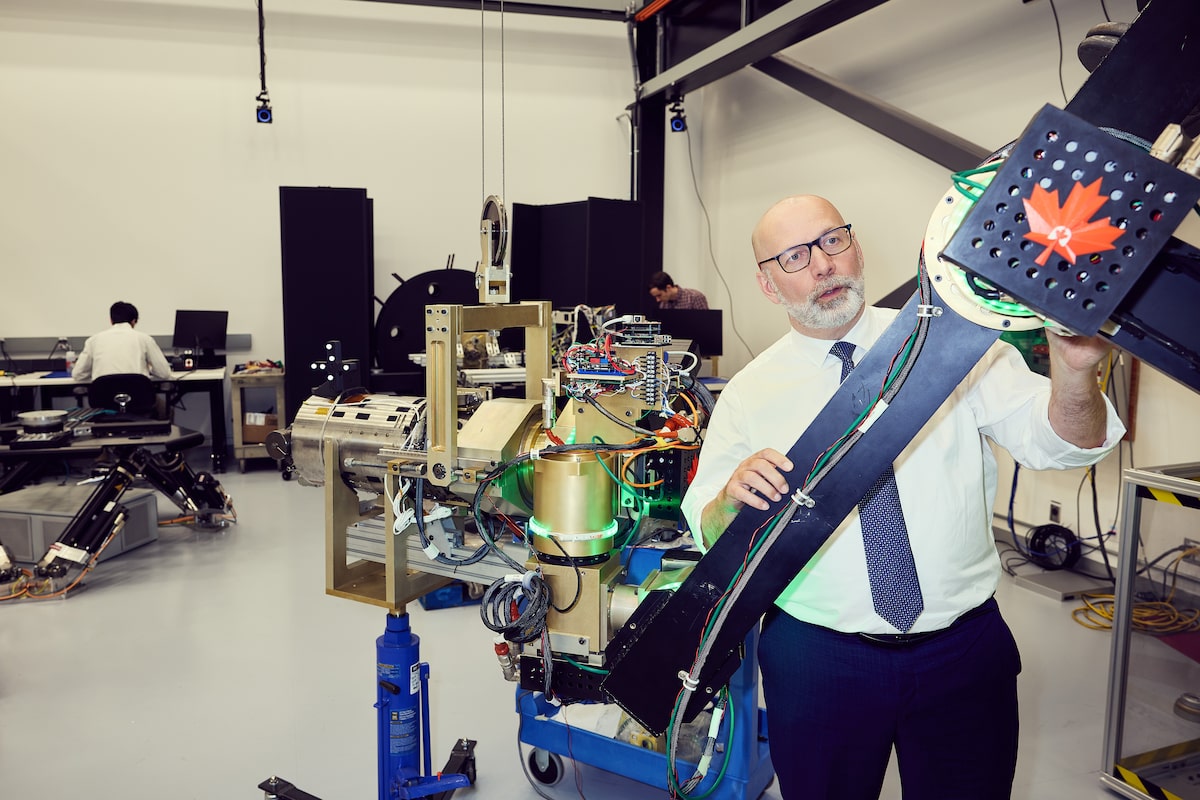

MDA Space Mike Greenley CEO says Canada tries to get large foreign corporations to set up a branch plant in the country, which creates jobs, but isn’t necessarily a productivity driver.The Globe and Mail

Canada’s productivity problem starts at the top – the ever-declining number of corporate head offices that call this country home.

Many Canadian companies have either relocated their corporate headquarters to the United States or mused about making such a move. The list includes Brookfield Asset Management Ltd., which shifted its head office to New York, and Barrick Gold Corp., which disclosed in February that it was mulling the merits of redomiciling south of the border.

It is a continuation of the hollowing-out of corporate Canada, a trend that has hampered our country’s economic competitiveness vis-à-vis the U.S. While it is tempting to blame President Donald Trump’s “America First” agenda, the truth is that successive Canadian governments have ignored our country’s yawning productivity gap for decades.

Labour productivity, which influences our standard of living, is the economic output for each hour worked. A Canadian worker contributes roughly $100 to the national economy compared with an American who expends the same time and effort, but contributes $130, according to a 2024 estimate cited by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

Opinion: Work American hours, earn European wages: Why Canada has the worst of both worlds

Although there is no silver bullet that can solve Canada’s productivity crisis, our elected officials can help remedy the problem by creating incentives to increase the number of corporate headquarters in Canada. Attracting and retaining more head offices would fuel more innovation and, thus, economic value, says Mike Greenley, chief executive of MDA Space Ltd.

“It’s generally been proven that where a headquarters is located will affect where the R&D occurs, and it’ll affect a lot of the supply chain,” Mr. Greenley said in a recent interview. (R&D refers to research and development.)

“And it certainly is going to affect where you register your intellectual property.”

Mr. Greenley, who has served as the top executive of Canada’s premier space company since 2018, walks the talk on improving productivity. Under his leadership, MDA, formerly part of U.S.-based Maxar Technologies, was repatriated to Canada in 2020 via a sale to a private-equity consortium led by Northern Private Capital.

After shedding its American ownership, MDA, maker of the Canadarm, went public in 2021 on the Toronto Stock Exchange.

Back in 2021, its revenue per permanent employee, which is a measure of productivity, was $224,000. Fast forward to 2025, and that figure has nearly doubled to $436,000 based on the company’s current forecasts.

Based in Brampton, Ont., MDA is one of the top R&D companies in Canada. It has tripled its number of registered patents since 2021.

“In Canada, we get very enamoured with foreign direct investment. We try to get large foreign corporations to set up a branch plant in Canada,” said Mr. Greenley, who is the Report on Business magazine’s reigning Innovator of the Year.

“That creates jobs and it’s good for our economy, but it’s not necessarily going to be a productivity driver.”

Linda Nazareth: To boost productivity, more young Canadians must go into the skilled trades

Foreign branch plants simply do not receive the bulk of a parent company’s investments in R&D. Nor do they spur the registration of new intellectual property in a foreign country.

There were 2,655 head office locations across Canada in 2023, down 0.3 per cent from the previous year, according to Statistics Canada. That might not seem like much of a decline until one considers the number of head offices domiciled in Canada has declined 4.9 per cent since 2012.

For his part, Mr. Greenley is urging municipal, provincial and federal governments to create more incentives for companies to establish and maintain their head offices in Canada.

Ottawa, for instance, could create two tiers of investment tax credits, with the highest rate favouring companies that maintain domestic head offices, he said.

His second recommendation, which focuses on the recruitment of top global talent, is for governments to offer temporary income tax breaks for individuals who relocate to Canada.

“We could give people advantages in their income tax for their first three or five years in Canada,” he said. “We need to be able to attract experienced executives to help Canadian companies scale and run a head office.”

Canada could also improve its corporate tax rates to make them more competitive with other jurisdictions. In doing so, it could offer a lower rate to domestically-headquartered companies, he said.

“The creation and retention of head offices in Canada is a really important tool because intellectual property will tend to stay where the head offices are,” he added.

MDA’s own “head-office mindset” is putting the company on track for future growth.

At the end of its second quarter, MDA’s backlog of signed contracts was worth $4.6-billion. As the company fulfills those orders over the next three years, it will pursue new contracts.

MDA, which is forecasting full-year revenues of $1.57-billion to $1.63-billion for fiscal 2025, could also pursue more acquisitions to expand its technological capabilities and geographic presence, potentially in the U.S. or Europe, he said.

Ottawa, meanwhile, is finally prioritizing defence as industrial policy, a strategic shift that also bodes well for MDA.

Indeed, Mr. Greenley argues that being Canadian is a boon because more countries want to become less reliant on U.S. technology.

“It’s a good time to be a Canadian company that’s headquartered in Canada and is looking to do international business.”

He’s got a point.