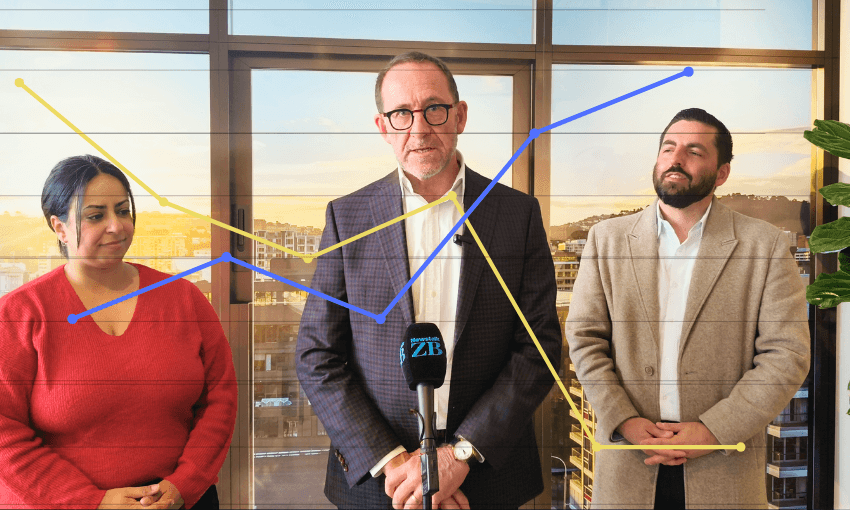

Wellington’s rate of housing construction has plummeted. Mayoral candidate Andrew Little thinks he has the solution – and he’s borrowed some ideas from our biggest city.

If there’s one statistic that should scare every Wellingtonian, it’s this: in the 12 months to May 2025, Wellington City Council consented 2.1 new dwellings per 1,000 residents. That’s the slowest rate among all 11 city councils in New Zealand.

The only silver lining is that it’s a slight improvement on 2024, when Wellington consented just 1.7 new dwellings per 1,000 residents. That was the worst annual result posted by any city council since 2013.

Since the market downturn began, construction in Wellington has plummeted, falling by 71% between 2023 and 2024. That was the steepest drop in the country, not just among city councils, but including all district councils and Auckland local boards, too. It wasn’t a fall from particularly lofty heights, either. Wellington’s most productive year in the low-interest-rate-fuelled boom was in 2020 when it consented 6.8 dwellings per 1,000 residents. Auckland and Christchurch topped out at 12.8 and 12.0 respectively.

Per-capita consents data for major city councils (Data source Stats NZ, graph Joel MacManus via Flourish)

This is way beyond a problem of housing supply and affordability. It’s a crisis that threatens the future of the city. If Wellington can’t build, it can’t grow. It will continue to decline, becoming increasingly economically and culturally irrelevant, its core infrastructure falling into greater disrepair while the burden of costs falls upon a shrinking pool of ratepayers.

Anyone who puts their hand up to be mayor needs to have an answer for how they would break the cycle and bring building back to the city. So what are the leading candidates offering?

Alex Baker, a former director at Kāinga Ora, is driving the conversation on land value rates and wants to replace developer contributions with targeted rates based on location-specific infrastructure requirements, which should act as an incentive for denser and better-located housing. Karl Tiefenbacher wants to introduce council “path smoothers” to work with major developers to streamline the consenting process, and wants to explore ways to lower building insurance costs. Diane Calvert has some vague language about removing red tape for developers (though it’s hard to put too much weight in her words, considering she vehemently opposed removing density restrictions in the District Plan, the biggest red tape blockade of all). Ray Chung doesn’t have any listed policies about housing development, but he, too, opposed increased density in the District Plan.

Then, there’s Andrew Little. I’ve been pretty critical of his policy stances thus far – unambitious, technocratic, campaigning against things that already aren’t happening. But it would be naive to pretend that he isn’t by far the most credible candidate and most likely to be mayor after October – and as such, his stance on housing is important.

Little announced his housing policy on Wednesday last week at the showroom for the upcoming Lido Apartments on Wakefield Street, a 138-unit development by Watson Group with prices starting at $395,000. “That’s just the sort of thing that we need if we’re going to attract young people, and mid-career people, and retain them here, and to make housing affordable for Wellington,” Little said.

The planned Lido Apartments on Wakefield Street (Image: Watson Group)

Little’s policy, as he describes it, aims for “a culture of ‘yes’ around new building consents”. He wants to give the council chief executive new KPIs to bring down the time it takes to process building consents, cut consenting fees to align with other cities, and make further changes to the District Plan to remove lighting and landscaping requirements. He also confirmed he would explore land value rates or other tools to encourage development in good locations.

His two most interesting proposals are both borrowed from successful Auckland Council initiatives. The first is the “qualified partner” approach; basically, major developments will each have a dedicated council staffer working with the developer to support consent applications. This is a change from the current approach, where consents are handled by a pool of staff, which can often lead to miscommunications and inefficiencies.

The second, and most significant, proposal is to create an urban development office, similar to Auckland’s Eke Panuku. Initially a council-controlled organisation, now an in-house council department, Eke Panuku serves as a “master developer” for Auckland, with the ability to buy and sell property on behalf of the council to drive urban regeneration projects. It’s best known for the Wynyard Quarter redevelopment and has worked on several other town centres and shopping precincts.

Some of the new housing developments proposed in Wellington since the new District Plan passed in 2024.

For an example of how this could work in Wellington, Little cited the Tawa Anchor Project. Residents and businesses in Tawa are pushing the council to renew the community centre and library at the heart of the suburb. It could be an opportunity to partner with private developers to build adjacent housing or retail to maximise the impact of the development. As Little put it: “The council still owns the land, and it’s still a council library, but you have the opportunity to have a higher development, which is owned by the developer with apartments or what have you.”

On the whole, I’m impressed by this announcement. I know some of the people who contributed to the policy. I won’t name them because I don’t want to get them in trouble with work, but they aren’t Labour people, just smart urban nerds who want good housing policy. The fact that Little has taken (most) of their suggestions on board is a positive sign for how he might lead as mayor – and who he might listen to.

What I appreciate about this policy is that it meets the moment. Wellington City Council has already pulled the biggest lever at its disposal last year by rewriting its District Plan to enable more density. There has been a small uptick in consents, and a noticeable change in the types of buildings being consented, but the new plan hasn’t made any real difference to housing supply.

The trouble is timing – by the time the change went through, the economy had cratered, and precious few developers wanted to invest in Wellington. Wellington needs to do more than just change the rules to attract development; it needs the council to take a direct leadership approach. It can’t just be a watchdog; it needs to be a herder, presenting opportunities, promoting investment, and encouraging them along.