The four offenders, together with 1000 other ACC “clients”, bombarded the MyACC app from November 1 last year with more than 10,000 fake travel reimbursement claims over a three-week period.

After 17 days, and after $652,857 worth of reimbursements were paid out, ACC discovered the fraud and managed to stop $919,717 in further payments from going out.

The theft meant ACC had to temporarily shut down the MyACC app, resulting in clients with genuine applications being unable to get them processed for some time.

Whaanga and her co-offenders earlier pleaded guilty to two charges each of accessing a computer system for dishonest purposes between November 1 and 17, 2023.

Whaanga and Te Hira faced additional charges of failing to appear.

‘She doesn’t think the law applies to her’

Whaanga’s co-offenders were sentenced by Judge Cocurullo last Friday, but the 32-year-old’s sentencing was adjourned after she turned up hours late.

Despite being irate at her wasting the court’s time, the judge reluctantly granted her bail, but on a 24-hour curfew, to reappear on Monday at 9am.

“But do not be one minute late,” he told her.

Come Monday 9am, and Whaanga was nowhere to be seen.

Her counsel, Rosalind Brown, told the judge she was running 20 minutes late because she was coming from the suburb of Enderley.

Judge Cocurullo issued a warrant for her arrest.

“I have had enough,” he said.

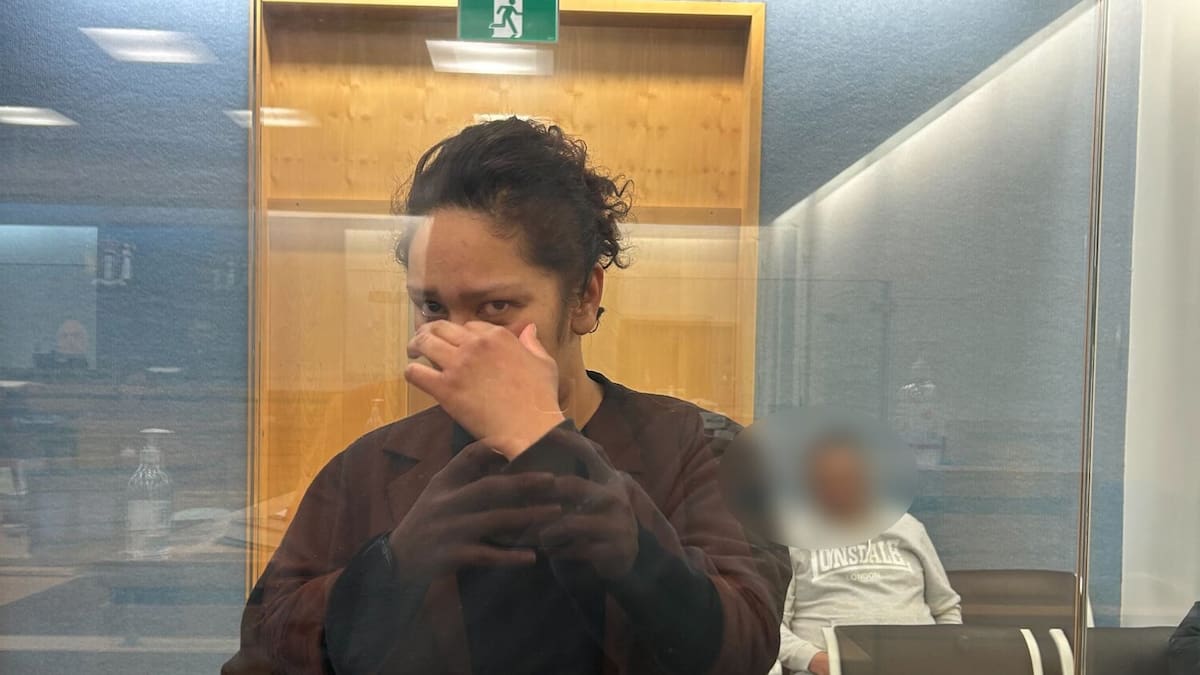

Whaanga then walked in at 9.24am and spent the rest of the week in custody before this morning’s hearing, in which the judge slammed her behaviour.

“With no disrespect to Ms Whaanga as a person, but of her behaviour, she is one of the most self-entitled women that I have seen coming before the court this year,” he told Brown.

From top left, clockwise: Jacqueline Whaanga, Ashleah Te Hira, Melody Haupokia-Kawerau, and Mohammed Hussain. Photos / Belinda Feek

He made the comments after Brown said her offending had come about because of a gambling addiction.

But the judge wasn’t buying it, saying he knew she’d said it to try to get an additional discount.

Whaanga had also told Brown that her five days in custody had “been a short, sharp, wake-up call”.

“She said she is motivated to comply and knows [prison] is her future if she does not take on the rehabilitative aspects.”

Judge Cocurullo toyed with the idea of a prison sentence, but was hamstrung by an issue dubbed “parity”, where a judge has to take into account what sort of sentence any co-offenders have received.

He ultimately agreed to give her home detention, but for longer than her co-accused, at eight months.

Her co-offenders received sentences of four, five, and six months’ home detention.

The judge said he would also judicially monitor her sentence, so if she puts a step wrong, she’ll get hauled back before the court.

‘The frenzied fraud’

Travel reimbursements help people with expenses involved in travelling to and from things such as medical appointments, treatment and rehabilitation.

To provide ease of access, ACC developed the MyACC app to allow clients to enter personal information, including bank accounts, and lodge requests.

In July 2023, ACC amended the rules and increased the limit for clients making travel reimbursement (CTR) claims.

Any claims over a certain threshold or quantity would be referred to staff for approval.

In what police describe as a “semi-organised and systematic course of action”, the group, with 1040 others, set about filing fake travel reimbursement claims.

The group would file their own, then get other associates in on the game, and would receive funds either directly from their own application or proceeds from others.

They would encourage associates to create a MyACC account and submit “numerous” applications, often within 15 minutes or less.

They used fake addresses as their “travel from address” and those addresses were used across “multiple clients and requests”.

The “travel to” addresses did not belong to treatment providers and were often houses, parks, vacant properties, or even paddocks.

As for their reason, they would submit “long-haul truck driver”, “social rehab”, or groupings of “intelligible letters”.

Once the maximum number of claims had been submitted, they would get a new associate to do the same thing.

ACC noticed the abnormal activity in mid-November and found a large number of “clients” were using similar travel addresses, reasons for travel, and sharing bank accounts and phone numbers.

ACC identified 1044 people had filed 10,093 fake claims, of which 4266 were paid, totalling $652,857.57.

A further 5827 requests, totalling $919,717.96, were stopped before payment.

The defendants were either directly or indirectly involved in about 25% of the fraudulent activity in that period.

Belinda Feek is an Open Justice reporter based in Waikato. She has worked at NZME for 10 years and has been a journalist for 21.