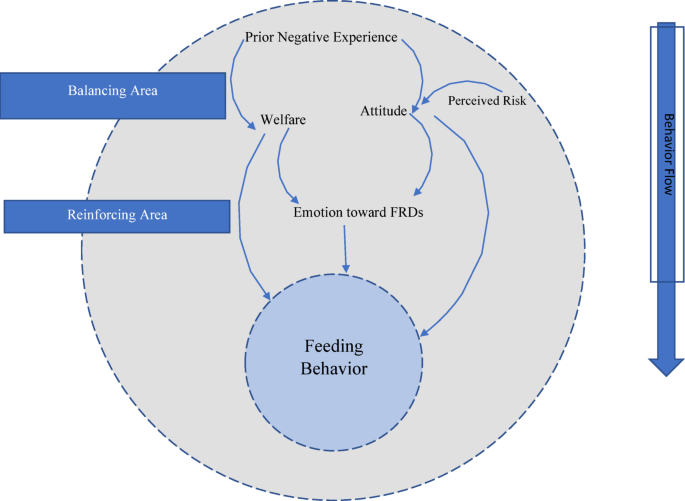

The causal chain underlying FRD feeding behavior is fundamentally rooted in attitudes toward FRDs, which are influenced by perceived well-being in their presence. This research has identified previous experiences with FRDs as a critical antecedent in this causal sequence. Negative encounters can significantly inhibit feeding behavior, transmitting an inhibitory signal through various layers of the model to the target variable. Conversely, in the absence of negative experiences, the continuation of FRD feeding behavior is predictable.

The proposed dynamics reveal a balancing loop (Balancing loops are those where one of the paths is not the same in terms of positive or negative influence as the other elements of the loop), where behavior can be altered by negative prior experiences with FRDs. Counteracting this is a reinforcing loop that demonstrates the positive effect of perceived welfare and attitudes towards FRDs on feeding behavior. In the absence of the balancing loop, local community behavior tends towards continued FRD feeding. However, interactions between the community and FRDs may lead to increased FRD populations, potentially resulting in human-animal conflicts and negative experiences. This activates the balancing loop, especially when perceived risk is incorporated into the model, leading to a downward trend in feeding behavior.

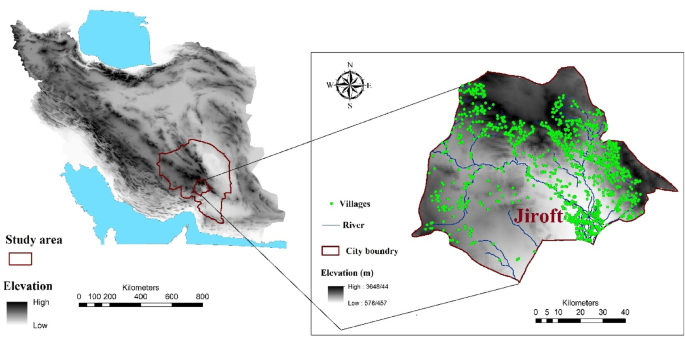

The causal model developed in this study suggests that adverse human-FRDs interactions can trigger confrontations with this species. Conversely, coexistence-oriented interactions may mitigate such confrontations. A representation of this local community decision field is illustrated in Fig. 5. Overall, the causal model developed shows that feeding behavior of FRDs is rooted in previous experiences, and if this experience is negative, the feeding behavior will stop, and if there is no negative experience, this behavior will continue. Therefore, the main trigger is the previous experience.

According to recent empirical research, perceived risk generally significantly moderates the relationship between emotions and attitudes toward FRDs and influences how individuals respond in various ways. Emotional responses, whether positive or negative, are critical for determining attitudes, particularly in contexts where there are perceived risks. The most important finding of this study was that it showed that human behavior in feeding FRDs is a function of his/her emotions and that what plays a role in the formation of emotions is a set of interactions, cycles, and causal chains, the most important variables of which are previous experience and perceived risk. It seems that more theoretical and empirical evidence is needed to explain the relationship between attitude and emotion and how perceived risk and previous negative experiences can affect these relationships.

Exploring what may play a role in this regard is a very complex relationship. From a psychological perspective, this can be explained based on the Cognitive-Appraisal Theory of Emotion33,34. Emotions are rooted in human cognitive Appraisal of events and situations. Such Appraisal are easily influenced by human values, beliefs, and attitudes towards an issue. Therefore, perceived risk can be a motivator or inhibitor of the effects of attitudes on emotional responses, where emotion ultimately results in behavioral effects. In the meantime, it would also be valid to refer to the theory of the risk as emotion hypothesis35. According to this theory, human responses to risks occur at two levels. The first level, referred to as the cognitive level, is where humans consciously assess the probabilities and consequences of risks, and the second level, known as the emotional level, is where humans experience emotions related to perceived risk. Using this theory, we can show that even if a person has a positive attitude towards something, if a strong sense of risk occurs under any event or experience, this emotion can overcome the human attitude and guide his emotional response.

A third theory is the Elaborative Likelihood Model36which also suggests that attitude change occurs along two lines: a central line (considering information carefully) and a peripheral line (relying on exploration and emotions). Further analysis of this theory suggests that when perceived risk is rising, people are more motivated to process information more carefully along the central line, and they are more likely to consider potential negative consequences, which can trigger negative emotions that naturally overshadow their initial positive attitudes. When perceived risk is falling, people are more likely to rely on peripheral cues and existing attitudes, which results in emotions that are consistent with their attitudes. Also from a social theory perspective, the Social Amplification of Risk Framework theory37,38 states that risk perception is amplified or reduced by the flow of information through social channels, including observation of the behavior of others. According to this theory, even if an individual has a positive attitude towards an issue or concept, social reinforcement can increase their perception of risk. This increased risk perception can trigger negative emotions that overwhelm their initial attitude.

In summary, it can be said from a theoretical perspective that the results of the present empirical study can be justified on the basis of the proposed theories, where cognitive assessments (conversion of negative assessments in the human cognitive system into negative feelings under conditions of high perceived risk), emotional responses (a high perceived risk can overcome positive attitudes by evoking strong negative emotions), information processing (a high perceived risk provides the motivation to carefully examine negative consequences that lead to negative feelings) and social influence (social responses can increase perceived risk and lead to negative feelings that ultimately dominate positive attitudes).

From an evidence perspective, risk perception significantly influences the interplay of emotional responses and attitudes. As we know today, individual backgrounds and experiences shape emotional responses, which leads to different risk perceptions39. So, Tompkins et al. (2018)40 believe that positive emotions can lead to risks being underestimated, while negative emotions can reinforce perceived risks. Positive emotional states led to greater support for wildlife conservation41while anxiety often results from perceived risks associated with encounters with wild animals, leading to negative attitudes42. Stinchcomb et al. (2023)43 argued that emotional responses depend on the context of the encounter and emphasized the need for tailored communication strategies to address specific fears and promote positive emotions. Günther & Shanahan (2020)44 emphasize that the perception of risks can increase negative emotions, which in turn can reduce support for conservation measures.

While our study has made contributions to understanding feeding behavior of FRDs and human-dog interactions, there are some limitations. We did not include cultural and religious factors in the analysis, given their sensitive nature. Also, future studies could benefit from utilizing a theoretical framework such as behavior Prioritization Matrix to better understand human behavior towards FRDs45. While this exploratory research provides a causal sequence architecture for predicting FRD feeding behavior, it also highlights the need for further investigation. Future studies should employ methods such as system dynamics and agent-based simulation to more precisely explore the dynamics of FRD feeding behavior, particularly focusing on the proposed reinforcing and balancing loops. Additionally, longitudinal causal modeling could illuminate new aspects of this complex behavior. Moreover, we recommend: Behavior-change campaigns that use community leaders, peers and influencers to indirectly educate people (especially for people who feed FRDs) can be very effective in changing attitudes toward FRDs46,47. This research is exploratory in nature, and the nature of such studies requires the use of a limited number of variables for theoretical frameworks.The outputs of the research were considered from the lens of other theories, simply to provide inspiration for other researchers in this field to develop other theoretical frameworks. Naturally, due to the complexity of human behavior in the vast context of psychological and sociological variables, combining diverse variables can explain the hidden dimensions of people’s behavior in feeding FRDs. As a limitation, the present research has only illuminated a portion of these unknowns.

Finally, although the integration of system dynamics and PLS-SEM offers a novel framework for understanding feeding behavior, future studies utilizing more comprehensive data—including qualitative insights and longitudinal measures—are necessary to validate and expand upon the current findings. A notable limitation of this study is the exclusion of certain positive motivational constructs, such as empathy, moral obligation, and social norms, from the model. Due to the exploratory design and limitations in data availability, these important latent variables could not be incorporated, despite their likely substantial influence on feeding behavior. Future research should seek to include these constructs in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of human motivations behind feeding FRDs. Addressing these limitations in subsequent studies will enhance our understanding of human-animal interactions and contribute to improved management strategies for FRDs in urban environments.

From a practical perspective, alongside the theoretical development of the article, the following recommendations can be offered: 1: Considering that previous negative experiences in interactions between humans and FRDs make the long-term control of this species more difficult, it is essential that community groups, alongside official media, strive to highlight the consequences of continued feeding behavior towards FRDs and clarify the future outlook of this behavior. 2: Educating children on this matter-especially in terms of maintaining their close connection with wildlife by preventing negative experiences in interactions with FRDs through school curricula-will be highly beneficial. 3: Given that the issue of managing FRDs has certain social and psychological roots, any control measures by responsible organizations must be conducted within the framework of ethical treatment of living beings, as any negative experiences in this regard can also disrupt public participation in this area.

Conceptual model of the subordination of feeding behavior to FRDs in the form of three driving, balancing and reinforcing area.