In early August more than 200 crates of manuscripts arrived in Timbuktu, the city in Mali famous for its ancient scholarship. The papers were squirrelled away in 2012 to protect them from jihadists. For the ruling junta, which took power in a coup in May 2021, and the Wagner Group, the Russian mercenary outfit that came a few months later, the manuscripts’ return is proof of success. They claim the insecurity that has plagued Mali for more than a decade, and which the West ostensibly did too little to stop, is at last being tackled.

The reality is different. Security in Mali, as in the rest of the Sahel region where there have been several coups in recent years, is getting worse. Unlike in other African countries in which they have operated, such as Sudan and the Central African Republic (CAR), Russians have failed to enrich themselves by exploiting minerals. But their brutal ways have caused tensions within the Malian army. These spilled into the open on August 11th when dozens of soldiers, including generals who have criticised Wagner, were purged. The saga is a reminder that, for all the worries about Russia’s meddling in Africa, its approach has severe limitations.

The rise to power of Assimi Goïta, the “interim” president who this year extended his term until at least 2030, was initially welcomed by Malians fed up with escalating violence from jihadists and separatists. Many were attracted by his pledge to assert Malian sovereignty after decades of French influence. His junta accused France and a UN peacekeeping mission of being combat-shy. It hoped Wagner would be keener to fight and more willing to obey Malian command.

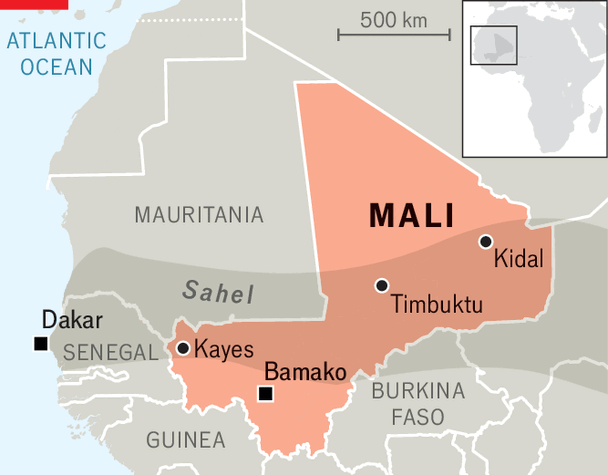

Map: The Economist

Map: The Economist

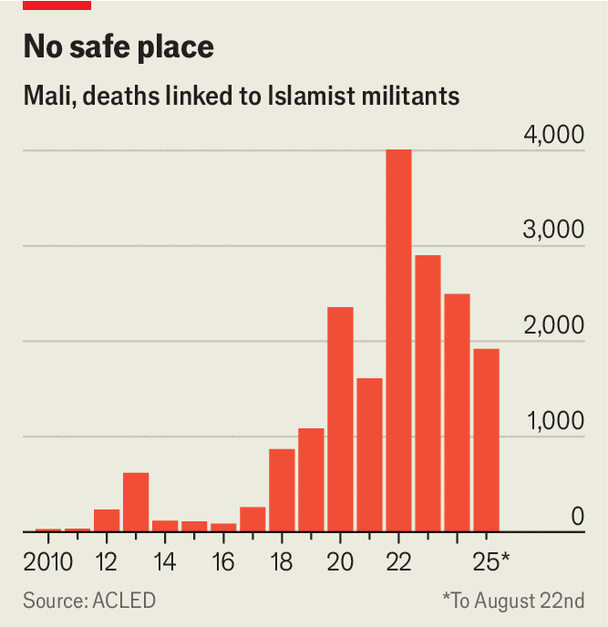

The Russians notched up early triumphs. In 2023 they helped the army win back control of Kidal, a northern city (see map). Yet that was a high point. Deaths in the country linked to jihadists averaged 3,135 per year from 2022 until 2024, compared with 736 over the previous decade, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data group (ACLED), a monitor (see chart). Nearly 2,000 people have already been killed this year, suggesting an upward trend. JNIM, the pre-eminent jihadist network in the Sahel, is expanding its footprint. In recent months it has attacked economic hubs such as Kayes, a town on the road to Dakar, the port capital of Senegal.

Chart: The Economist

Chart: The Economist

This is not solely Wagner’s responsibility. Security was bad when it arrived. Some 2,000 Russian fighters are in Mali today, compared with some 5,000 French troops across the Sahel at the peak of a French-led anti-jihadist mission that began winding down in 2021, and 12,000 UN peacekeepers before the coup. Islamist violence is even worse in neighbouring Burkina Faso, where few Russians are deployed

But the way Wagner operates is unsuited to counter-terrorism, as a report published on August 27th by the Sentry, an American investigative outfit, explains. Murdering ordinary Malians, it turns out, is a bad way to win over ordinary Malians. Informants have dried up. In the past year 80% of civilian deaths were at the hands of Malian soldiers or Wagner, rather than JNIM, notes ACLED. “They just kill people [they suspect] without verifying first,” one soldier told the Sentry. It argues that Wagner runs “open-air prisons” by blockading towns it believes contain jihadists. Russians have supported a militia that stands accused of ethnic cleansing. Increasingly separatists and jihadists are working together against Wagner and the army.

Nobody hires Russian mercenaries for their love of the Geneva Convention. But Wagner has angered many in the army. The Sentry’s report says the group is racist towards Malians, takes army equipment without asking and defies commands. Russians get priority in evacuations, adding to disenchantment in the Malian rank-and-file. A military official told the Sentry that Wagner “are worse than the French, they think my men are more stupid than them. We have gone from the frying pan to the fire.” Wagner also seems to be a mediocre fighting force. In 2024 some 84 Russians were killed by separatist rebels in a battle, after a sandstorm grounded air cover.

Nor has Wagner managed to muscle in on mining in Africa’s second-largest gold producer. The junta has resisted entreaties to transfer large gold mines run by Western firms. Instead the regime has used the Russian spectre to extract more money from the industry that provides more than half of tax revenues. “Assimi and his team are not fools, we did not reject one invader to open the door to another one, like they did in CAR,” says an official at the mining ministry. Wagner’s attempts to grab a smaller-scale “artisanal” sector have failed as well. Initially it was paid out of Mali’s security budget. Today Moscow may be footing at least some of the bill.

Though there is little appetite for a return of the French-allied political elites toppled five years ago, the soldiers who were purged for complaining about the Russians were reflecting public sentiment. “I was one of the Malians who fiercely believed that this Russian presence would change something,” says an academic. “Today I am really disappointed.” A construction worker in Bamako, the capital, reckons that “they lost 80% of their popularity because they cannot lead a country…the social fabric crumbles from day to day.”

It is less clear whether serious tensions extend to the top of the junta, raising the prospect of another coup. Some analysts suggest that Mr Goïta wants to diversify away from Russia (Sadio Camara, the defence minister, has closer links with the Russians). America may be betting as much. The Trump administration has sent officials to Bamako and other regional capitals to discuss the potential for security help and mineral deals. Turkey, a source of drones, is increasingly influential with Mr Goïta. Gulf states are active, too.

That hints at a problem for Russia. Wagner’s appeal was that it was willing to fight battles the West or the UN refused. But two years after the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin, Wagner’s figurehead, the Kremlin is reining it in. In June its presence in Mali was rebranded as Africa Corps, with a clearer line of responsibility to Moscow. This was a tacit admission of Wagner’s shortcomings. The junta may wonder why it should rely on a more risk-averse Russia, when it could forge closer ties to America or rising middle powers. When guns are for hire, African governments do not need to renew their leases. ■