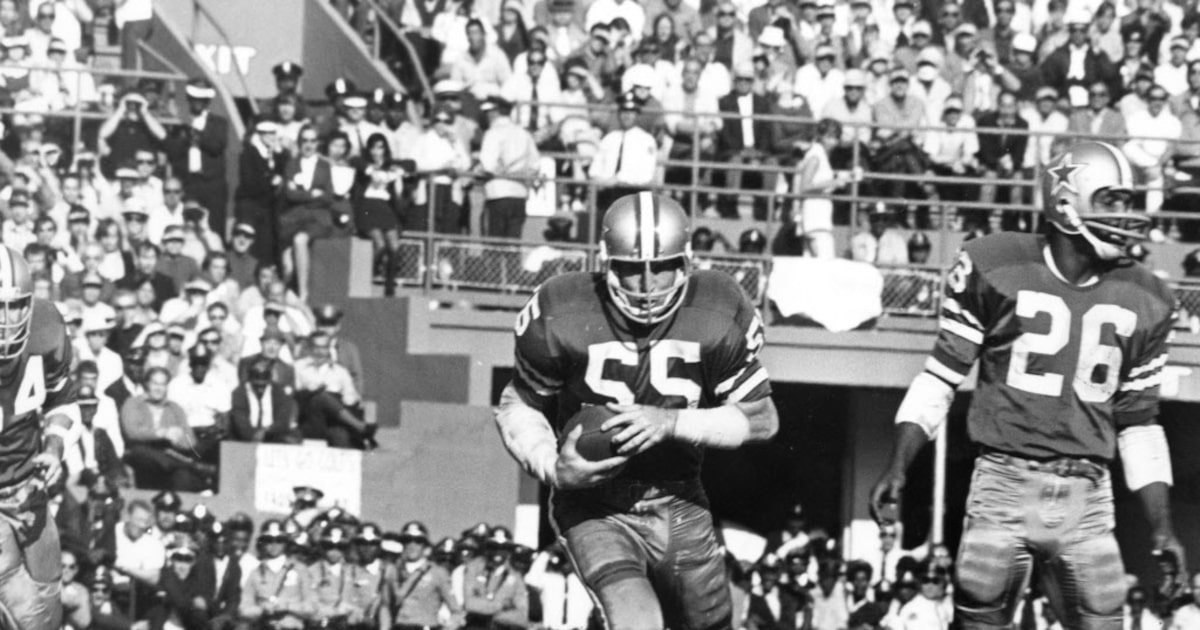

Lee Roy Jordan, whose ferocious play in the 1960s and ’70s made him one of the most feared linebackers in college and the NFL and the dean of the Dallas Cowboys’ fabled Doomsday Defense, died Saturday in Dallas hospice of kidney failure, his son, David, said. He was 84.

Over a career in which he played an integral role in Bear Bryant’s first national championship at Alabama as well as the Cowboys’ first Super Bowl win, Jordan raised the standard of play with relentless effort and preparation, and by demanding the best from his teammates.

A five-time Pro Bowler, NFC Defensive Player of the Year and member of two all-time SEC teams as well as the Cowboys’ Silver Anniversary team, he was the first player inducted into the Ring of Honor by Jerry Jones in 1989.

Former Dallas Cowboys and Hall of Fame football players Lee Roy Jordan (left) and Mel Renfro visit on the sideline before being introduced with other 1960’s players before the Cowboys game with the Los Angeles Rams at AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas, Sunday, October 1, 2017.

Tom Fox / Staff Photographer

Cowboys

“With fearless instincts, leadership and a relentless work ethic, Jordan was the embodiment of the Cowboys’ spirit,” Jones, the owner and general manager, said in a statement. “Off the field, his commitment to his community was the centerpiece of his life after retiring in 1976.

“His legacy lives on as a model of dedication, integrity and toughness.”

In an era when middle linebackers such as Ray Nitschke, Willie Lanier and Dick Butkus ruled football, Jordan held his own with anyone.

“Lee Roy was as good as any linebacker in football,” long-time broadcaster Verne Lundquist once said.

“Period.”

Born the fourth of seven children on an Excel, Ala., farm without electricity, Jordan was discovered by Jerry Claiborne, one of Bryant’s assistants, when he was scouting a player from another team. Because Jordan wasn’t particularly big or fast, the staff considered him a marginal prospect at first. Once on campus, he quickly persuaded his coaches otherwise.

Driven by Bryant, whom he considered a second father, he accelerated the Bear’s timetable for restoring Alabama to the upper tier of college football. He was the best player on the Crimson Tide’s national title team in 1961 and finished fourth in the Heisman Trophy voting as a senior.

He carved a permanent place in Alabama lore with 31 tackles in the Tide’s 17-0 win over Oklahoma in the ’63 Orange Bowl.

“If they stay in bounds,” Bryant once said, “ol’ Lee Roy will tackle ’em.”

Friend or foe, it didn’t matter with Jordan. Near the end of the Senior Bowl, a blow to the face cost Jordan four of his front teeth. An athletic trainer stuffed gauze in his mouth to try to stop the bleeding, but Jordan would have none of it.

Spitting out the bloody gauze, he yelled, “Let’s go!” and returned to the field, where he led a goal-line stand to preserve the South’s win.

“It may have been a meaningless game for some of them,” his Alabama teammate, Bill Battle, wrote in Jordan’s memoir, Lee Roy: My Story of Faith, Family and Football, “but it wasn’t for Lee Roy.”

Jordan didn’t let up at practice, either. After the Cowboys selected him with the sixth pick of the first round in 1963, he drew the ire of some veterans for demanding more effort from teammates. He knew no other way to play.

Dan Reeves, then a rookie, found out as much in a scrimmage. Running through what he thought was a hole, he learned why Jordan’s teammates called him “Killer.”

Jordan’s famous forearm shiver shattered Reeves’ facemask and busted his lower lip.

If that’s what he does to his teammates, Reeves wondered, what does he do to opponents?

“Dan,” Jordan said when he asked him that question later, “if my grandmother put on a helmet and ran the ball for the other team, I would have to tackle her.”

From 1963-76, including a 12-year period in which he made 154 consecutive starts at middle linebacker, no Cowboy made more tackles than Jordan. Fast or not, he was always around the football. He’s one of only five linebackers with more than 30 interceptions and 15 fumble recoveries. He credited Tom Landry’s Flex defense for taking advantage of his skill set. Because he was, at 6-1, 220 pounds, one of the smallest players at the position, he relied on his quick first steps and preparation.

He credited the player he replaced, Jerry Tubbs, with helping him learn the nuances of Landry’s revolutionary defense. Jordan studied so much film, he once asked for a projector in contract negotiations.

Jordan’s dedication and devout Christian faith led the Cowboys to assign him as a roommate with Don Meredith on the road and the night before home games. Jordan’s job was to make sure Dandy Don made it back to his room before curfew. Jordan served as what he called Don’s “babysitter” for six years until his friend’s premature retirement at 31.

Often asked if his greatest feat was the 31-tackle game in the Orange Bowl, Jordan wrote in his memoir, “I laugh and say my greatest accomplishment in football was being able to get Don Meredith back to the room in time for bed-check … most of the time.”

Though he cultivated a ferocious reputation on the field, he was a gentleman off of it, a family man beloved by teammates.

“On the field, he was the best middle linebacker I’ve ever seen,” wrote Reeves, whose long career included head coaching stints in Atlanta and Denver.

“Off the field, he is one of the best people I’ve ever known.”

Reeves once lived at the end of the same Lake Highlands street as the Jordans along with the families of Chuck Howley, Tony Liscio and Dave Manders. David, the oldest of Lee Roy and Biddie’s three sons, said growing up there it seemed like everyone’s dad was a Cowboy.

Former Dallas Cowboys linebacker Lee Roy Jordan unveils his number in his dedicated area during the Ring of Honor Walk unveiling ceremony at The Star in Frisco on Monday, August 21, 2017. (Vernon Bryant/The Dallas Morning News)

Vernon Bryant / Staff Photographer

“He was one of those guys, it took a lot to make him mad,” David said of his father. “But you didn’t want to get him there. He was unwavering. Firm but fair.

“He would give you three chances before he broke the belt out on you.”

He was also quick to hug and tell his boys he loved them, David’s wife, Melanie said, a practice that immediately endeared him to her.

Once his career was over in 1976, Jordan purchased a couple of lumber yards and worked for decades. He remained in good health, David said, until a few years ago, when dementia as a result of what they believe to be chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, made him more reticent even than usual.

Yet he continued to travel with his wife of 62 years back to Alabama to see friends and family. Upon returning from one of those trips this summer, David said, they noticed a sharp decline in his health. In the last six weeks, he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma and renal failure. The family checked him into Faith Presbyterian Hospice, where he died early Saturday morning.

Besides his wife, whom he met at Alabama, he is survived by three sons and eight grandchildren.

Before his father’s death, David said, one of his favorite teammates, Roger Staubach, visited along with his wife, Marianne.

“You were my boss,” the Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback told Jordan. “You were the baddest guy on the football field.”

Dallas Cowboys Ring of Honor members (from left) Mel Renfro, Lee Roy Jordan, Tony Dorsett, Roger Staubach, Chuck Howley and Randy White pose with a shot of the Dallas skyline in the background fter meeting at The Dallas Morning News to discuss the Ring of Honor induction procedures.

LOUIS DELUCA / 191035

Despite what his dementia took from him, Melanie said, he was also the guy who “could always say, ‘Love you.’ ”

A memorial service will be held at 11 a.m. Sept. 19th at Christ the King Catholic Church in Dallas.

Twitter/X: @KSherringtonDMN

Find more Cowboys coverage from The Dallas Morning News here.