Study population

Non-emergency cardiac interventions of 193 consecutive patients were deferred at Ulm University Heart Center, Germany, between March 19th, and April 30th 2020 (study group). 15 patients were excluded because their planned intervention was not performed by the end of the follow-up period. Of the remaining 178 patients, 74 patients (41.6%) underwent cardiac catheterization, 49 patients (27.5%) transcatheter heart valve intervention, 47 patients (26.4%) electrophysiological procedure and 8 patients (4.5%) device implantation. The planned intervention was deferred by a median of 23 (19, 38) days. During the corresponding seasonal period of the previous year 2019 (March 19th–April 30th 2019) 216 patients were scheduled for a non-emergency cardiac intervention at our tertiary care center, of whom 214 patients received their procedure as planned (control group). Distribution of the interventions did not differ significantly between the groups (p = 0.397). In the control group 93 patients (43.5%) underwent cardiac catheterization, 47 patients (22.0%) transcatheter heart valve intervention, 57 patients (26.6%) electrophysiological procedures and 17 patients (7.9%) device implantation.

Baseline data on the originally planned intervention date of both groups are displayed in Table 1. In both cohorts, the median age was slightly above 70 years (study group 72.31 ± 11.18 vs. control group 70.29 ± 13.19 years; p = 0.105) and most patients were male (study group 59% vs. control group 66%; p = 0.142). Patients of the study group suffered more frequently from known coronary artery disease at baseline (76.7% vs. 65.4%, p = 0.026) and had a significantly higher heart rate at admission (73 (64, 85) vs. 68 (60, 80) beats per minute (bpm), p = 0.014). Furthermore, study group patients had higher cTnT levels at baseline (22.0 (10.75, 36.5) vs. 15.5 (9, 28) ng/l, p = 0.030). In the control group, significantly more patients had a positive family history for cardiovascular disease (26.6% vs. 13.8%, p = 0.004). Moreover, EHRA class was significantly higher in the control group (1.4 ± 0.8 vs. 1.4 ± 0.6, p = 0.006). Beyond that, no significant differences were observed in patients` baseline characteristics.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics on the originally planned intervention date: study group (deferred patients) and control group (regularly treated patients).Predictors of CHF with clinical progress during prolonged waiting time

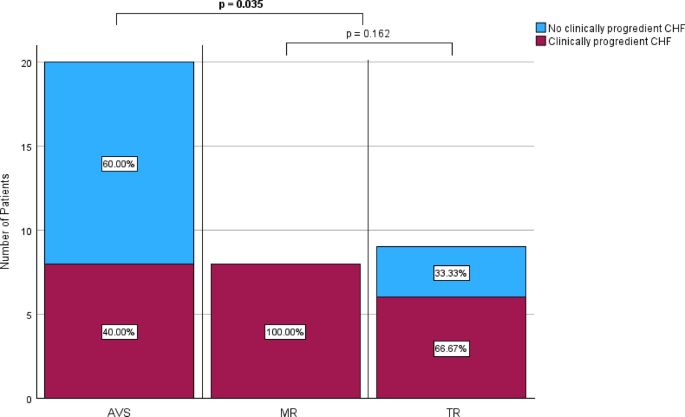

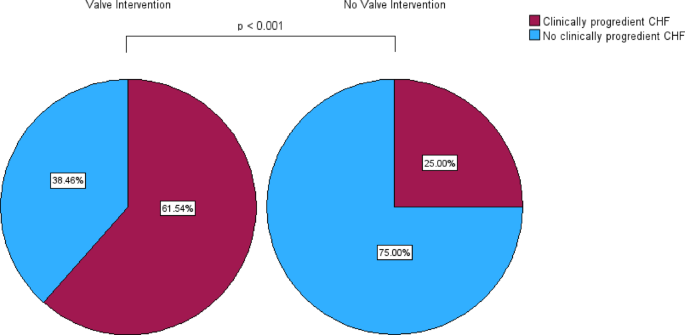

Univariate analysis showed that planned transcatheter heart valve intervention (p <0.001), older age (p <0.001), severely reduced LVEF (p = 0.003), known cardiac arrhythmia (p = 0.010), cTnT levels (p = 0.030), known chronic kidney disease (p = 0.032), and planned cardiac catheterization (p = 0.041) were associated with CHF with clinical progress during the waiting time (NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml in combination with worsening of clinical symptoms, including dyspnea, emergency heart failure hospitalization, and LVEF) (supplementary table 1). After exclusion of variables with high collinearity (The corresponding Pearson correlation analysis is shown in supplementary table 2), multivariate logistic regression analysis of all significantly tested variables showed that only planned heart valve intervention was independently associated with CHF with clinical progress (OR 34.632, 95%-CI 3.337–359.404; p <0.001) (Table 2). ROC-analysis yielded an AUC of 0.657 (95%-CI 0.576–0.738), a sensitivity of 44.4% and a specificity of 85.7%. Of the patients for whom repeated data assessment was available, 24 of 39 (61.5%) with planned transcatheter heart valve intervention had clinically progredient CHF during the waiting time, in contrast to only 30 of 120 (75.0%) with other cardiac procedures (p <0.001) (Fig. 1).

Table 2 Multivariate binary regression analysis for baseline characteristics on the originally planned intervention date for congestive heart failure (NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml in combination with clinical symptoms) with clinical progress during the waiting time (including univariate predictors p < 0.05).Fig. 1

Proportion of deferred patients (study group) with and without clinically progredient congestive heart failure (CHF, NT-proBNP > 900 pg/ml in combination with worsening of clinical symptoms) during the waiting time in the groups with and without planned heart valve intervention.

CHF on the actual intervention date

On the actual intervention date, 89 of 178 deferred patients (50.0%) had a plasma NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml, indicating CHF (control group with regular treatment time 85 of 214 patients (39.7%), (p = 0.078)). All patients with NT-proBNP levels > 900 pg/ml on the actual intervention date additionally had symptoms and thus were diagnosed with CHF. Based on the presence of CHF after the prolonged waiting time, deferred patients were divided into two groups. Baseline data of the patients with and without CHF, assessed on the actual intervention date, are shown in Table 3. Patients with an NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml were of older age (77.0 ± 8.8 years vs. 67.6 ± 11.4 years; p <0.001) and suffered more often from chronic kidney disease (26.4% vs. 12.3%; p = 0.033). Moreover, they were significantly more frequently scheduled for transcatheter heart valve intervention (43.8% vs. 11.4%; p <0.001). In contrast, patients with an NT-proBNP level of ≤ 900 pg/ml were more likely to be smoker (44.4% vs. 27.8%; p = 0.038) and were more often planned for cardiac catheterization (52.3% vs. 30.3%; p = 0.003). All other baseline characteristics were similarly distributed in both populations. The waiting time also did not differ between patients with and without CHF (22 (19, 36) vs. 25 (18, 40) days; p = 0.335).

Table 3 Baseline characteristics of deferred patients (study group) with and without congestive heart failure (NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml in combination with clinical symptoms) on the actual intervention date.Clinical impact of the presence of CHF on the actual intervention date

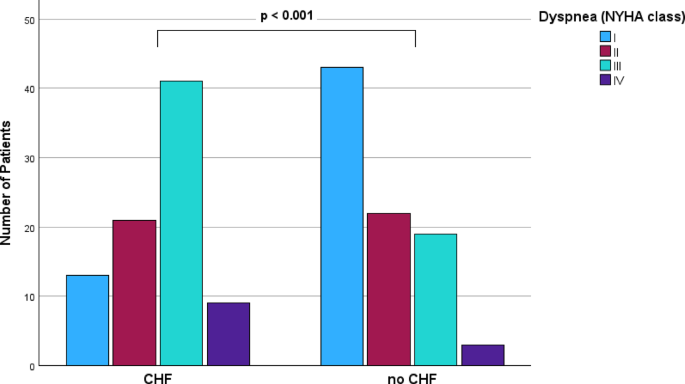

To further evaluate the clinical impact of CHF, deferred patients with CHF on the actual intervention date (NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml in combination with clinical symptoms; n = 89) were compared to those who were CHF-free at this time point (NT-proBNP level ≤ 900 pg/ml/no symptoms; n = 89). Clinical characteristics of both groups are displayed in Table 4. Median NT-proBNP level at admission was 2346 pg/ml (1512.5, 4330 pg/ml) in the group with and 228.5 pg/ml (111, 505 pg/ml) in the group without CHF. Patients with an NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml had higher NYHA classes (2.5 ± 0.9 vs. 1.8 ± 0.9; p <0.001, Fig. 2) and more impaired LVEF (2.2 ± 1.2 vs. 1.8 ± 1.0; p <0.001) when compared to those with an NT-proBNP level ≤ 900 pg/ml. Moreover, they had higher cTnT (30 (19, 52) vs. 11 (8, 19) ng/l; p <0.001) and creatinine levels (122.18 ± 78.24 vs. 91.08 ± 27.72 µmol/l; p <0.001) on the actual intervention date. Furthermore, patients with CHF were admitted more frequently as an emergency for their indented cardiac intervention (43.8% (39 patients) vs. 23.9% (21 patients); p = 0.005) and the interventional hospital stay lasted longer (3 (2, 8) vs. 2 (1, 3) days, p <0.001).

Table 4 Clinical characteristics of patients with and without congestive heart failure (NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml in combination with clinical symptoms) on the actual intervention date.Fig. 2

Dyspnea according to the NYHA-scale at admission for deferred patients (study group) with and without congestive heart failure (CHF, NT-proBNP > 900 pg/ml in combination with clinical symptoms) on the actual intervention date.

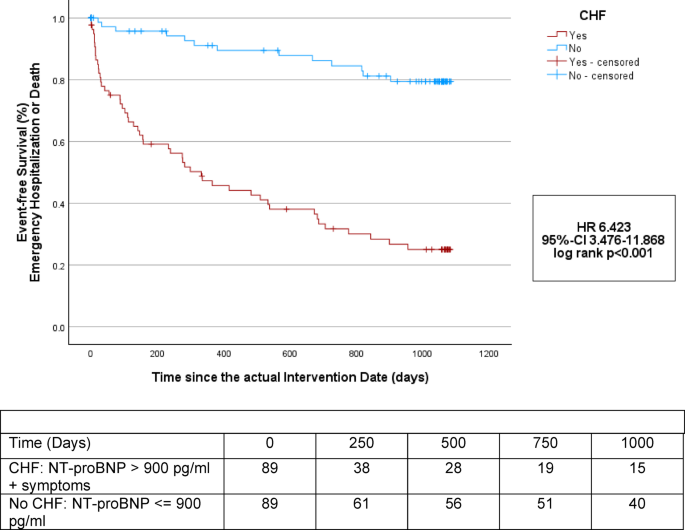

Rates of emergency hospitalization or death over the postinterventional 36-month follow-up period were significantly higher and time-to-event was shorter in the group with CHF compared to the group without (57.3% vs. 14.8%, p < 0.001; HR 6.423, 95%-CI 3.476–11.868, log rank p < 0.001). Event rates were 42.7% (38 patients) vs. 6.8% (6 patients) at twelve months, 52.8% (47 patients) vs. 11.4% (10 patients) at 24 months and even 57.3% (51 patients) vs. 14.8% (13 patients) at 36 months after the procedure (each p <0.001). The first postinterventional event of emergency hospitalization and death occurred in patients with CHF after 334 (80.5, 365) days, and in patients without CHF after 365 (279.75, 365) days (p = 0.002). (Table 5). The corresponding Kaplan–Meier survival curves are shown in Fig. 3.

Table 5 Postinterventional clinical outcomes of patients with and without congestive heart failure (NT-proBNP level > 900 pg/ml in combination with clinical symptoms) on the actual intervention date.Fig. 3

Kaplan–Meier estimators of the time to emergency cardiovascular hospitalization or death for deferred patients (study group) with and without congestive heart failure (CHF, NT-proBNP > 900 pg/ml in combination with clinical symptoms) starting from the actual, deferred intervention date.

Subgroup analysis: deferred patients with planned transcatheter heart valve intervention

In total, 49 deferred patients were scheduled for transcatheter heart valve intervention. Of these, 29 patients (59.2%) had aortic valve stenosis (AVS), 18 (36.7%) atrioventricular valve regurgitation, of which eight (16.3%) suffered from mitral valve regurgitation (MR) and ten (20.4%) from tricuspid valve regurgitation (TR), and two patients (4.2%) were scheduled for intervention of mitral valve stenosis (MS). Overall, 39 out of these 49 patients (79.6%) were diagnosed with CHF on the actual intervention date. In detail, 20 of 29 patients with AVS (69.0%), eight of eight patients with MR (100%) and nine of ten patients with TR (90.0%) had an NT-proBNP level of > 900 pg/ml. Of the patients for whom repeated data measurement were available, eighth of 20 patients with AVS (40.0%), eighth of eighth patients with MR (100%), and six of nine patients with TR (66.7%), had clinically progredient CHF during the waiting time. Risk was even higher in patients with planned intervention of the atrioventricular valves (mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge-repair (M-TEER) or tricuspid transcatheter edge-to-edge-repair (T-TEER)) compared to patients scheduled for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) due to AVS (82.4% vs. 40.0%; p = 0.035 after Bonferroni correction). Between patients with planned intervention due to MR and TR, rates of CHF were not significantly different (p = 0.162 after Bonferroni correction) (Fig. 4).

Proportion of study group patients with and without clinically progredient congestive heart failure (CHF, NT-proBNP > 900 pg/ml in combination with worsening of clinical symptoms) during the waiting time depending on the type of planned heart valve intervention.

Impact of the predictor heart valve intervention on clinical outcomes in case of deferral

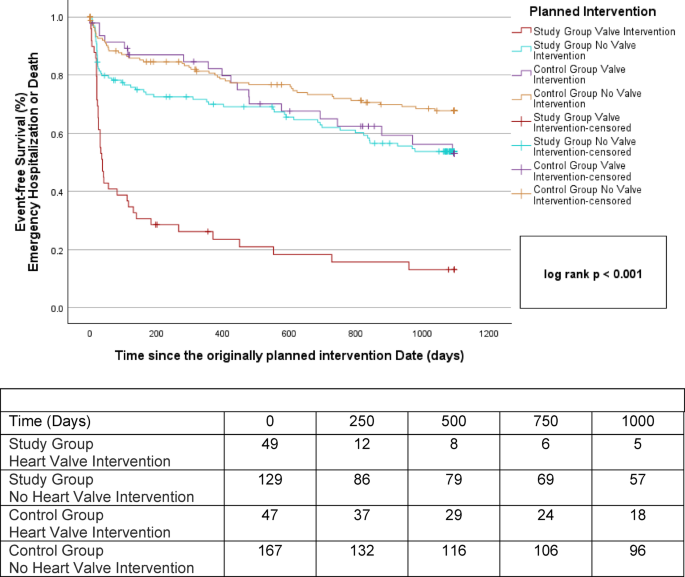

To further evaluate the effects of deferral in patients scheduled for transcatheter heart valve intervention, clinical outcomes were compared separately with those of regularly treated controls of the previous year 2019 (n = 47). No significant differences in baseline characteristics on the originally planned intervention date were observed between the subgroups of patients with planned heart valve intervention in the study and control group (Table 6). On the actual intervention date, deferred patients had significant higher NYHA-classes compared to the control group (2.9 ± 0.6 vs. 2.6 ± 0.7, p = 0.009) (supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, the planned transcatheter heart valve intervention had to be performed more frequently in the context of an emergency hospitalization (61.2% (30 patients) vs. 0% (0 patients), p <0.001). (Table 7). Emergency hospitalization or death occurred significantly more frequent during the 36 months after the originally planned intervention date in deferred patients compared to the regularly treated controls and time-to-event was shorter (83.7% vs. 40.4%, p <0.001; HR 4.37, 95%-CI 2.50–7.64, log rank p <0.001). Such an event occurred in 36 patients (73.5%) in the study group vs. seven patients (14.9%) in the control group after twelve months, in 39 (79.6%) vs. 13 patients (27.7%) after 24 months and in 41 (83.7%) vs. 19 patients (40.4%) after 36 months (each p <0.001). The first event of emergency hospitalization and death, starting from the originally planned treatment date, occurred in deferred patients of the study group after 38 (21, 311) and in the regularly treated patients of the control group after 366 (366, 366) days (p <0.001). (Table 8).

Table 6 Baseline characteristics of patients scheduled for transcatheter heart valve intervention: study group (deferred patients) and control group (regularly treated patients).Table 7 Characteristics of patients scheduled for transcatheter heart valve intervention on the actual intervention date.Table 8 Outcomes of patients scheduled for transcatheter heart valve intervention following the originally planned intervention date.

To substantiate the impact of the index disease on the outcome of emergency hospitalization or death following deferral, time-to-event of patients without the predictor heart valve interventions were also compared between the study and the control group. Notably, patients scheduled for other interventions, who were deferred and who were regularly treated had a comparable time-to-event during the 36-months follow-up period after the originally planned intervention date. Furthermore, while patients in the study group with deferred heart valve interventions had a shorter time-to-event then patients with other interventions, no such difference was observed in the control group. The corresponding Kaplan–Meier survival curves are also shown in Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier estimators of the time to emergency cardiovascular hospitalization or death for deferred patients (study group) and regularly treated patients (control group) with and without planned heart valve intervention starting from the originally planned intervention date.