August is coming to an end and while the eco-conscious reader may feel a twinge of guilt about all those tons of carbon we expended flying out and back on our holidays, few actually do anything about it. Fewer still opt to buy carbon offsets to atone for their summer splurge.

And justifiably so. A high-profile drive to sell carbon offsets to air passengers appears to have been a resounding failure.

CO₂ sequestration is a lower priority in our holiday financial planning than, say, the quality of the cocktails in a resort bar. It is not a consideration at all for most of us. This provides insights into the unreliable alignment of financial and carbon budgets.

In 2021, I wrote that carbon offsets for air passengers lacked just two ingredients for success: credible prices and enough customers. I calculated that British Airways was pricing passenger offsets at €8-€10 per ton. I doubted whether anyone could reliably lock up that amount of carbon for such low prices.

In subsequent years, hard-nosed reporting by the FT, among others, achieved what theorising columnists could not. It pulled the rug out from under the claims of some prominent offset operators, revealing evidence of greenwashing, double counting, and other statistical hyperbole.

This ensured that uptake of passenger offsets for tree planting and the like remained modest — somewhere in the low, single-digit percentages.

EasyJet gave up buying offsets on behalf of passengers in 2022. British Airways stopped offering offsets as an add-on purchase for customers in 2023. Around the same time, United Airlines scrapped its own offset sales scheme. This year, The Irish Times reported that Ryanair had quietly followed suit.

These days, businesses and charities marketing offset schemes are more likely to pitch to corporate purchasers than individual consumers.

Indifference and distrust are likely culprits for the belly flop of passenger offset schemes, according to Lorraine Whitmarsh, professor of environmental psychology at Bath University. Travellers have “some awareness” that air travel increases planetary warming, she says, “but most people do not think about it when planning a holiday”.

She adds that offset schemes would have done better if they had been funded by a default supplement on ticket purchases, from which customers could opt out if they wanted. Economy passengers are already lumbered with endless add-ons for boarding, luggage, seat positions and food. It is hardly surprising that few of them checked the box to buy carbon offsets, too.

My cynical suspicion is that voluntary schemes permitted airlines to appear to be doing something about emissions while shifting moral responsibility to resentful customers. These days, they have mostly internalised carbon reduction efforts. Legislators and regulators are meanwhile imposing minimum standards on them at the usual legato tempo of the official battle against climate change.

Prof Whitmarsh believes low prices were one reason some passengers thought offsets were a waste of money. The marketplace spielers are still barking out bargain prices, even as the crowd of shoppers has melted away. Prices quoted online by independent offset vendors go as risibly low as £4.30 per ton of carbon.

How realistic is the average of £16 per ton I calculated from the quotes of carbon bucket shops on the web? Not realistic at all, says Sam Van den Plas, policy director of Carbon Market Watch, a Brussels-based non-profit. A better proxy, he says. is the market price of emissions certificates issued under the EU’s cap-and-trade scheme. Big polluters, including airlines, are required to buy these to cover some of their activities.

This makes better sense to me than using the price set by the UK’s small, volatile emissions trading scheme.

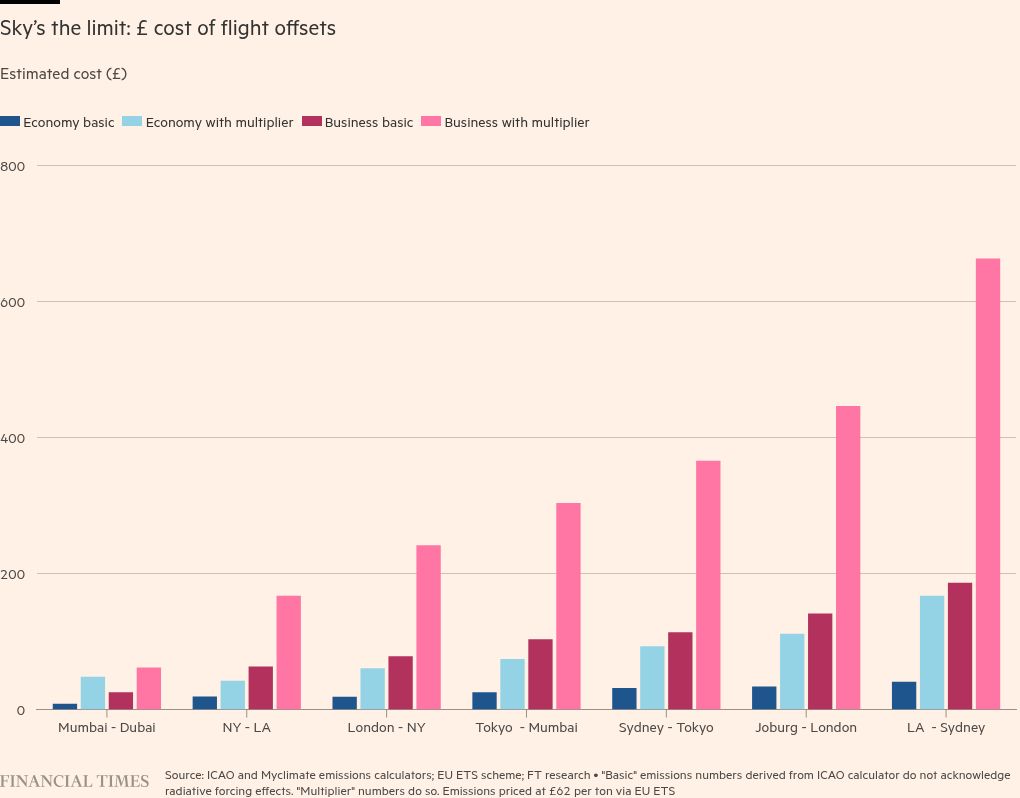

I therefore used a €72 (£62) per ton EU trading price to plot more realistic offset costs for trips made by fictional FT Money reader Philomena Fogg. I got baseline emissions from a popular calculator provided by the International Civil Aviation Organization, an agency of the UN. This does not allow for the multiplier effect that dumping greenhouse gases at high altitude has on global warming.

The ICAO calculator may be popular because its underestimates make offsets cheaper. As a reality check, I priced the same trips using a second calculator that adjusts for the multiplier effect.

Axiomatically, the wider the range of estimates, the lower the credibility of any estimate within that range. But it would at least give Philomena plenty of choice, even when buying offsets at fancy continental prices.

Let us assume our globe-trotting protagonist can thwart deep vein thrombosis while flying cattle class, scheduled and direct, from Los Angeles to Sydney. She would shell out a mere £41 for offsets, based on ICAO emissions numbers. If she treated herself to business class and a fancier calculator, the charge would be £663.

You can see why Philomena might say “to heck with it!” and not bother. During her exhausting journeys, airlines would have bombarded her with propaganda about their efforts to reduce emissions via participation in mandatory schemes and the recycling of paper drinks coasters.

As for me, after flying I will continue to send money to peatland restoration projects in the UK and Ireland. In future, I will at least know how to categorise these payments. They will not be offsets, precisely calibrated to cover greenhouse gases emitted. They will be donations to charity.

Jonathan Guthrie is a writer and adviser; jonathanbuchananguthrie@gmail.com