Samantha Donovan: A team of archaeologists has discovered a human jawbone that’s nearly two million years old in Georgia, a country that’s often described as being at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. They believe the jaw is the oldest human relic ever excavated outside Africa. And they’re hoping it’ll give us more clues about prehistoric human settlements in Eurasia. Julia Bergin prepared this report.

Giorgi Bidzinashvili: In such a small place, we find human rests, human bones. Big information about humankind.

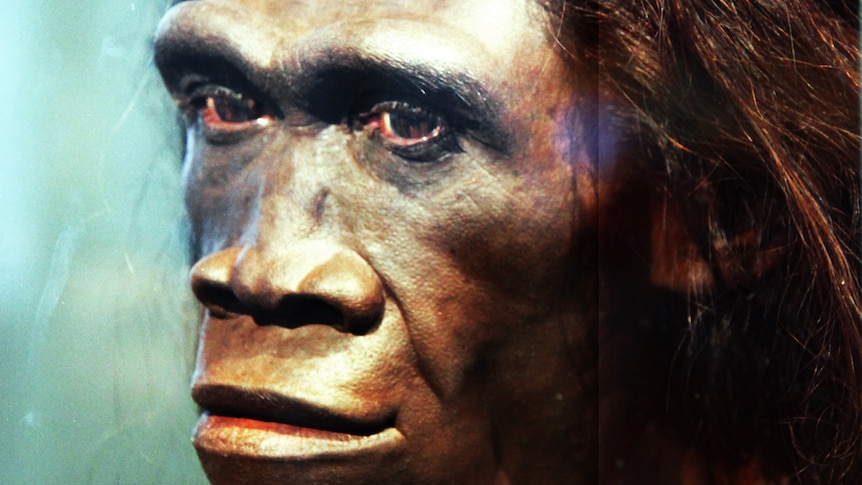

Julia Bergin: Stone Age archaeologist Professor Giorgi Bidzinashvili has been digging on a small, dusty plot of land alongside a team of fellow archaeologists from around the world. That site, around 100 kilometres from the Georgian capital and no bigger than two car parking spaces, is called Orozmani. It’s here that the group has just uncovered a human jawbone estimated to be 1.8 million years old. That makes it the oldest human remains ever found outside of Africa.

Giorgi Bidzinashvili: This site gives us opportunity for wider understanding of human evolution and early dispersal out of Africa because Orozmani is the oldest site with human presence dated back 1.8 million years old.

Julia Bergin: It’s not the first time archaeologists have made significant discoveries in this part of Georgia about prehistoric human settlements. They’ve previously dug up teeth and human skulls. University of Helsinki’s associate professor Mikka Tallavaara, who was also on site, says these remains offer clues to the way early hunter-gatherer species lived and migrated around two million years ago.

Mikka Tallavaara: And if you want to study like how adaptable these early humans were, in which kind of environments they were able to live, these are key locations.

Julia Bergin: The team also found a cache of stone tools and animal fossils on site, which give clues about what these early humans ate. It comes as archaeologists around the world are slowly chipping away at dig sites to uncover more about where we came from. University of Sydney archaeology lecturer Dr Melissa Kennedy says depending on what you’re trying to find, this process can take years.

Melissa Kennedy: When you’re going out on a dig, it’s very long days. You’re generally starting at sort of five, six in the morning and working through to sort of eight or nine at night, probably about six days a week. Everyone thinks that it should move really fast, that it’s just moving dirt. But it’s not. Every bucket of dirt has to get sieved. You’re collecting bags of soil for the archaeobotanist to look for ancient seeds. The bones get collected. They get brushed and analysed by the person who does the zoology. So, you know, there’s so many different people going on an excavation that it takes just such a long period of time.

Julia Bergin: And while archaeological teams always set out with a plan to find something, Dr Kennedy says digs are typically full of surprises and thrilling discoveries.

Melissa Kennedy: When you find something, it’s absolutely amazing. Anything, you know, even just a small bit of bone or a small piece of a broken pot, you know, that’s something that someone had, you know, 5,000 years ago, 10,000 years ago, even, you know, 200 years ago. So I work in sort of the prehistoric period. So the time before written records. And so we don’t have, you know, wall reliefs or writings that people can tell us about the past. So it’s really the only way we can learn how people actually lived and what they did.

Samantha Donovan: Dr Melissa Kennedy is an archaeology lecturer at the University of Sydney. That report from Julia Bergin.