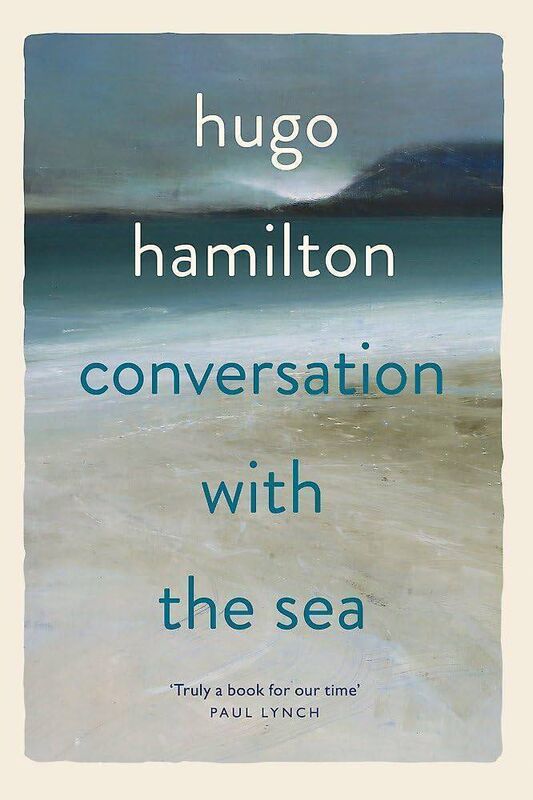

Hugo Hamilton’s latest novel, Conversations with the Sea, centres on Lukas Dorn, a forlorn, lonesome middle-aged German man who has come to stay in a guest house on Achill Island following the breakdown of his marriage.

Lukas writes in his journal, wanders the moonlit bogs, watches rapture-pursuing surfers from a distance, observes an escaped horse run into the Atlantic, and collects a sick, elderly friend from the hospital.

The sea is a metaphor for the engulfing force of history: there are those who surf atop the surface (Lukas rejects the surfers’ well-meaning hipster invitation to chase the sublime moment), and there are those like Lukas, who literally and figuratively is at risk of drowning under the mighty pull of the waves.