This study highlights strong spatial overlaps between key industrial sectors and MPAs and other areas of marine conservation value in the northwestern Mediterranean. Economic activity is closely linked to these areas, with over half of the total port revenues in the region generated within or near (within 2 km) MPAs. Fisheries and aquaculture landings, leisure boating infrastructure (berths), and cruise passenger activity exhibit particularly high levels both inside and near MPAs, as well as within or adjacent to other areas of conservation value. Notably, planned energy developments, including offshore wind farms and hydrogen pipelines, are also located within or in close proximity to MPAs. By contrast, cargo activity, along with desalination infrastructure, are predominantly located outside MPAs. Regarding vessel traffic, only large fishing vessels using active gears exhibited significantly higher densities within MPAs compared to areas outside them.

Trends from 2000 to 2023 show declines in fishing activity (reflected by decreasing seafood landings, revenues, and the number of fishing vessels), cargo transport, and local (small) cruise passengers, alongside increases in recreational boating, international cruise traffic, total port revenues, and desalination capacity. Additionally, the analyzed data indicate the potential future development of energy projects such as hydrogen pipelines and offshore wind farms. The findings also point to widespread impacts from these industrial activities across multiple GES descriptors. This suggests that the integrity of MPAs and other conservation zones—cornerstones for achieving GES, defined as a state in which marine ecosystems are healthy, productive, and resilient enough to support both biodiversity and human use—could be compromised by industrial activities. These impacts are particularly associated with sectors that have expanded in the region since the 2000s, such as leisure boating and international cruising, as well as emerging energy and water industries, including offshore wind farms, hydrogen pipelines, and desalination plants.

The relevance of Mediterranean MPAs in the context of expanding sea industrialization

The industrialization of the seas began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the development of fisheries, commercial and defense shipping, and the conversion of coastal sites for shipbuilding and processing. This process has continued over the centuries, expanding to include coastal and marine tourism, mineral and energy extraction, and, more recently, renewable energy development and marine biotechnology32. Although the industrialization of the seas was once primarily limited to coastal areas, technological advances over the past decades have made even the most remote parts of the ocean accessible1,35.

As ocean industrialization continues to expand—driven by growth in sectors such as those analyzed in this study—MPAs have become increasingly important tools for ensuring that economic development does not come at the expense of marine ecosystem health36,37. Marine conservation through MPAs should be a top priority in light of the biodiversity crisis that is severely affecting marine ecosystems36. This is particularly important for Spain which, at 23%, is among the 20 countries in the world with the highest share of fragile ecosystems in the Biodiversity and Ecosystem services index38. It is equally important for the entire Mediterranean Sea, a hot spot for marine biodiversity39 and one which is threatened by human activities and global change40. All around the world, maritime infrastructure and traffic (shipping, cruising, and recreational boating) are growing and expanding rapidly, whereas professional fishing is in decline20,37,41,42,43,44. These trends are found in our study region: professional fishing and local cruise activity have declined since the early 2000s, whereas leisure boating, international cruise activity, water infrastructure (desalination plants) and energy infrastructure (offshore wind farms and hydrogen pipelines) have increased or are expected to increase dramatically in the future, driving the next phase of industrialization in the north-western Mediterranean Sea and raising new red flags for MPAs. A recent review of interactions between 14 ocean sectors revealed that 13 sectors (all of which have been included in our study) had interactions that produced unidirectional, negative ecosystem impacts45, the one exception being the telecommunications sector. Another study described the pressures imposed by 17 industrial sectors on GES areas, which represent the ultimate objective of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008/56/EC)2. In this context, it is of paramount importance to protect the existing MPAs from further industrialization.

The three counties of the Costa Brava region, which comprise around 38% of the Catalan coastline, are responsible for about 35% of the non-market ecosystem service value of the Catalan coast29,46, highlighting the considerable economic value delivered to local citizens by adjacent protected ecosystems. In Europe as a whole, ecosystem services from Natura 2000 protected sites (terrestrial and aquatic combined) are estimated to be worth between 223 and 314 billion euros47,48. Although the initial economic costs of MPAs may outweigh any immediate economic benefits (because they often impose new management on marine activity by restricting or altering their existing spatial distribution), over the long-term, MPAs can make an important contribution to these maritime activities (reviewed by10). In this context, there is a need for further analyses of environmental and socioeconomic trade-offs among multiple and equally important environmental, economic, and social objectives, such as biodiversity conservation, marine renewables expansion, the protection of small-scale fishery livelihoods, sustainable aquaculture production, and food and nutritional security—not all of which may be fully reconciled49,50,51.

MPAs play a major role in shaping and defining seascapes by conserving ecological integrity and guiding sustainable human activities36,37. Pörtner et al.52 proposed a mosaic of interconnected protected and shared spaces, including intensively used spaces, to strengthen self-sustaining biodiversity, the capacity of people and nature to adapt to and mitigate climate change, and nature’s contributions to people. Maritime planning should embrace, maintain and respond to this logic. Mediterranean areas such as the Costa Brava, which were classified as a combination of highly natural and seminatural areas by Brenner et al.29, could meet the criteria of two of the various distinct ‘scapes’ defined by Pörtner et al.52 for Earth’s major biomes, namely “Large intact natural areas” (strictly protected areas and large, intact wilderness spaces assimilable to protected areas) and “Varied mosaic of nature and people” (spaces shared by people and biodiversity). However, the new wave of industrialization in the Mediterranean Sea, beginning in the early 2000s, but part of an ongoing industrialization of the world’s oceans during the second half of the 21st Century32, may transform these ‘scapes’ into “Heavily modified anthromes” (areas with cities, intensive fisheries, modified coast and energy infrastructure)52. If this happens, the United Nations’ goal to protect 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030, agreed upon by 196 countries and bodies such as the European Commission, will be very difficult to achieve.

Upscaling of the results

The outputs of our study can be scaled-up. They can contribute to the process of weighing up the economic benefits of ocean activities against the environmental costs associated with them, as well helping decision-makers by providing greater clarity on spatial aspects of ocean economy sectors and marine conservation, and ensuring sustainable outcomes and equitable sharing of benefits with coastal communities. Our study has been carried out on the local scale and therefore reflects local realities and challenges more specifically than larger (national or sea basin) analyses, and this can be particularly useful for planning ocean economic activities53. MSP is usually conducted on a broad scale54,55, and often fails to avoid or minimize the conflicts that arise between local communities and industrial activities operating, or projected to operate, inside or nearby Mediterranean MPAs (see e.g16,17,56.,). In this context, the outputs of our interdisciplinary study favor a more tailored and localized approach to the planning of industrial activities, and one that must consider not only marine protected areas (Natura 2000 sites) but also other areas of conservation importance and a temporal approach (not only spatial) of human activity at sea.

Beyond the planning of maritime activities

Beyond managing industrial activities to avoid damage to MPAs, an equitable downscaling of production and consumption that increases human well-being and enhances ecological conditions has also been proposed as a new vision for the seas to ensure not only environmental, but also social sustainability57,58. Market-based values are the core drivers of today’s global biodiversity crisis, and their primacy in many decisions needs to be reduced and balanced with the non-market instrumental, relational, and intrinsic values that are integral to why nature matters to people59. In order to incorporate nature’s diverse values into decision-making and to leverage transformative changes toward more just and sustainable futures, combinations of value-centered approaches are needed59. Industrialization can affect territorial visions and policies, which fall into three categories: anthropocentric (prioritizing human interests), biocentric-ecocentric (emphasizing living beings or nature’s processes as a whole) and pluricentric (encompassing all such views with no single ‘centre’)59. Depending on the number and type of companies and industries that begin to operate in a particular site, and the degree to which they attract other activities associated with them, the mix of these industrial sectors in a particular regional environment can alter a region’s vision for the future and the policies being pursued. This trend, widely studied on land, is now also accelerating in the marine environment and careful planning is needed to deal with it. In addition, safeguarding ocean sustainability requires transdisciplinary efforts to manage the activities of the many stakeholders, including governments, corporations, and civil society, and guide them toward responsible ocean stewardship1.

Policy implications

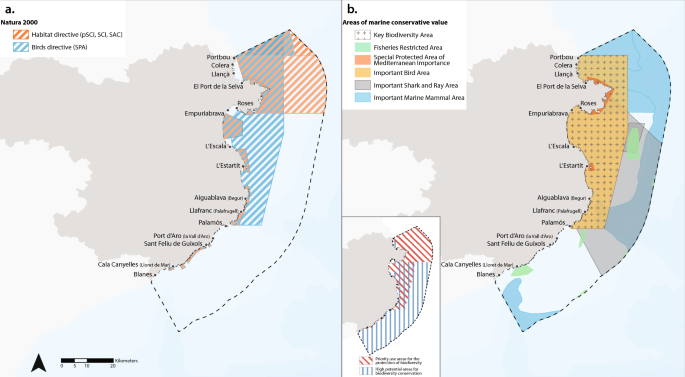

As the expansion of human activity into the ocean accelerates, the marine natural systems, and the goods and services that they provide, deteriorate2,3. In past decades, the economic development of countries was mostly measured by industrialization targets and environmental consequences were ignored60. Such polices now require urgent re-examination to avoid further environmental deterioration, and to stay in line with international recommendations such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework61 and the 14th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG): “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”62. This is especially important when new industrial activities are contemplated in areas that have hitherto been dedicated mostly to biodiversity conservation, or others that remain in relatively in good health. The Costa Brava region, 44% of whose marine territorial waters (Spanish) are protected, is a good example of this. Furthermore, other areas of conservation value—such as IMMA, ISRA, KBA, and IBA (Supplementary Table S1)—which together cover 77% of the study area, are currently unprotected but possess outstanding biodiversity value. These areas are strong candidates for future MPAs and should therefore be carefully considered in marine spatial planning—not just the Natura 2000 sites. MPAs will play an important role in the EU’s Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, which aims to effectively protect 30% of European seas by 2030, with one-third (10%) under strict protection63. However, in the Mediterranean Sea, just 9.7% of EU waters are currently covered by Natura 2000 sites, compared to 27.6% in the Greater North Sea and 15.5% in the Baltic Sea64. On the other hand, the EU biodiversity strategy for 2030 also recognizes that besides biodiversity conservation objectives, there is a need to bring substantial health, social and economic benefits to coastal communities, and the EU as a whole. In this sense, many studies have shown that MPAs can benefit coastal communities by helping professional fishing and local tourism business in a number of different ways (reviewed by10,12,13,65). Indeed, our study showed that around 60% of the total port revenues in the study area (for the year 2023) occurred in ports located inside or in the vicinity (2 km buffer) of Natura 2000 sites, and approximately 75% of total revenues occurred in ports located inside or in the vicinity of the other MPA categories, demonstrating that substantial economic value was delivered to local citizens by the MPAs surrounding them. Our results suggest that industrialization must be avoided, or limited, in the case of coastal regions that currently have the highest environmental values, and large areas of protected waters or areas of high conservation value. In particular, emerging industrial activities such as offshore wind energy should be prohibited within or adjacent (a buffer zone of at least 10 km should be maintained, Brill et al.66) to MPAs, with this restriction extended to all zones designated for marine biodiversity conservation67.

The management and conservation of the world’s oceans require a synthesis of spatial data on the distribution and intensity of human activities, and the overlap of their impacts on marine ecosystems18. One of the fundamental tools for managing spatial data and achieving a balance between human activities and biodiversity conservation in the EU and its Member States is MSP68,69. However, in many Mediterranean countries, MSP is still in its infancy55 and where MSP exists, it presents several challenges55. For example, the recently approved Spanish Maritime Spatial Plans30 revealed an extensive overlap between industrial sectors and important marine conservation areas, illustrating the challenges marine biodiversity conservation in Spain faces due to the expanding industrial sectors of the ocean economy. Early mapping of current and projected interactions between industrial activities and all types of areas of conservation value—regardless of their regulatory status—is essential for understanding and managing human activities that may impact ecologically important areas.

Contrary to the Precautionary Principle, industrial activities are, at times, expanding ahead of exploration, with licenses granted before a consensus is reached on how to mitigate the environmental impacts of the activity1. This also goes against the idea of using an Ecosystem-Based Approach (EBA), an important underlying principle within MSP, to achieve a sustainable use of the marine environment, and ultimately contribute to healthy seas across Europe53. This occurs because key principles that typically define the EBA—such as the application of the Precautionary Principle, holistic consideration of all ecosystem components, and the involvement of relevant stakeholders—are often not upheld when there is urgency to develop certain sectors, such as offshore wind energy, where the need to address climate change and energy security tends to accelerate development processes28,70. Furthermore, given the poor environmental status prevailing in parts of the European seas—such as sectors of the Baltic and North Sea Exclusive Economic Zones—implementing an EBA that supports the achievement and maintenance of GES will require a substantial reduction in the adverse impacts on marine ecosystems resulting from both existing and planned human uses of maritime space71. Apart from the ecological impacts described, industrial activities have major socioeconomic consequences, often at the expense of coastal communities1. Many coastal communities are excluded from the high-level decision-making processes that define some industrial sectors, such as renewable and non-renewable energy projects, cruising and shipping32,72,73. These large-scale businesses are associated with the exclusion of coastal communities that rely on small-scale, local businesses such as fishing and coastal tourism20,32,73. Benefits disproportionately flow to economically powerful states and corporations, whereas the harms are largely affecting developing nations and local communities1,74, which can have severe consequences for the health and well-being of coastal communities that depend on healthy seas75,76. These failures can be avoided or better addressed when policies align with a more comprehensive suite of biodiversity goals and local citizen’s values. Ignoring or marginalizing locally-held values in planning activities can leave a legacy of mistrust, and create conflicts with local (coastal) communities, jeopardizing program outcomes over time15,77.

Finally, policymakers and spatial planners should consider the impacts that certain industrial activities may have on the seascape and landscape of Mediterranean MPAs and other marine conservation areas, such as those in the Costa Brava. These areas provide significant scenic, amenity, and socioeconomic value to local and tourist communities who enjoy their views78, and their appreciation—along with other leisure and sport activities within marine parks—is often enhanced by the surrounding natural scenery79. For instance, the offshore wind industry, as a large-scale industrial enterprise, has the potential to significantly transform the seascape80,81. Consequently, the economic and social losses related to the degradation of seascapes in Mediterranean MPAs—key components of marine goods and services—caused by offshore wind farms could be substantial28.

Gaps, limitations and future research

Despite the insights provided by this study, several gaps and limitations remain. Our study reveals substantial gaps in understanding the environmental pressures exerted by maritime infrastructures and activities on MPAs and other marine areas in the Mediterranean that serve conservation functions but lack legal designation. In particular, the impacts of hydrogen pipelines and water desalination plants remain poorly quantified, with offshore wind farms also requiring further study. Our study demonstrates that, as ocean industrialization accelerates through the expansion of these sectors, there is an urgent need to assess their environmental impacts on MPAs and other areas of high conservation value. Understanding these pressures reveals another important gap: the lack of natural capital metrics to evaluate GES in MPAs and other conservation areas. GES is a normative conceptual framework currently applied at broad geographic scales defined by individual countries; in our case study, this corresponds to the Levantino-Balear region as defined in the Spanish MSP plans30. Currently, GES indicators are only applicable at broad geographic scales, which complicates their application to specific conservation areas such as MPAs. Effective planning and management of human activities in these areas would be significantly improved if GES could be downscaled to the level of individual MPAs, supported by clearly defined indicators and metrics.

Our study has certain limitations, particularly the inability to analyze trends across different size categories and types of activity within each economic sector, due to data constraints—specifically, the lack of detailed information on the intensity of use within each sector. For instance, within the fishing sector, the ecological footprint of small-scale professional and recreational fishing fleets is generally considered to be lower than that of industrial trawling82. Similarly, the ecological impact of non-motorized craft (e.g., sailing boats and kayaks) is typically less significant than that of motorized vessels (e.g., yachts and jet skis)41. These distinctions are important and should be addressed in future research as more detailed and disaggregated data become available.

Another limitation of this study is that, for all sectors considered, a direct link between vessel density and environmental impact has not always been clearly established. For example, while there is a well-documented body of literature demonstrating a direct relationship between fishing effort density and habitat impact (e.g83.,), as well as between shipping route density and the risk of wildlife collisions84, the evidence remains more limited for other sectors such as cargo and passenger transport. In these cases, studies linking vessel density to specific ecological impacts remain relatively scarce or indirect, highlighting the need for further research.