Messianic delusions. Paranoia. Suicide. Claims of AI chatbots potentially “triggering” mental illness and psychotic episodes have popped up in media reports and Reddit posts in recent months, even in seemingly healthy people with no prior history of these conditions. Parents of a teenage boy sued OpenAI last week, alleging ChatGPT encouraged him to end his life.

These anecdotes, especially when paired with sparse clinical research, have left psychologists, psychiatrists, and other mental health providers scrambling to better understand this emerging phenomenon.

STAT talked with a half-dozen medical professionals to understand what they are seeing in their clinics. Is this a new psychiatric condition, likely to appear in the next edition of diagnostic manual? Or is this something else? Most likely, it’s the latter, they said.

An extended conversation with a chatbot can wrench a person who is prone to delusions from reality, and most of the professionals said they had heard from a small number of patients who described such experiences. But if you don’t have a mental illness or a genetic predisposition to psychosis, rest easy. Your risk of developing psychosis from talking with a chatbot is minimal, said Karthik Sarma, a psychiatrist at the University of California, San Francisco, and founder of the UCSF AI in Mental Health Research Group.

“If you’re just using ChatGPT to, I don’t know, ask the question, ‘Hey, what’s the best restaurant with Italian food on 5th Street?’ I’m not worried people who are doing that are gonna become psychotic,” said Sarma.

While chatbots are not inducing psychotic breaks in most people, these machines are not harmless. Half a billion people globally use OpenAI’s tools, including its ChatGPT chatbot, according to a July report. Most providers did not see any patients with AI-aided psychosis before the spring, which lines up with the April release of ChatGPT 4.0, which its makers and users alike suggested was too agreeable, or “sycophantic.” Medical professionals say this behavior can fuel delusional thinking for the roughly 1% of people in the U.S. with psychosis.

Slingshot AI, the a16z-backed mental health startup, launches a therapy chatbot

Many mental health professionals heralded the development of large language models and chatbots as alternate therapy options for people with poor access to psychological and psychiatric services. But the worrisome reports and anecdotes resurface old questions about the ethics of these technologies and the safeguards that mitigate their harms.

Just how common AI-mediated delusions are is unknown, but medical professionals are racing to start studies of their frequency and causes so that they can guide patients on the use of chatbots. It’s vital that researchers and, more importantly, companies like OpenAI move quickly, given the chatbots’ potential harmful effects, said Nina Vasan, a psychiatrist who runs the Lab for Mental Health Innovation at Stanford.

“We shouldn’t be waiting for the randomized control study to then say, let’s make the companies make these changes,” said Vasan. “They need to act in a very different way that is much more thinking about the user’s health and user well-being in a way that they’re not.”

The depictions in the media and from clinicians suggest that people are mainly experiencing delusions, and for that reason, clinicians prefer “AI-mediated delusions” rather than the snappier but less accurate “AI psychosis” to describe the phenomenon.

Psychosis can include disorganized speech and auditory and visual hallucinations. Delusions are just beliefs that a person continues to assert in the face of contrary evidence, often mirroring their cultural and technological context.

Typically, these delusions are triggered by drug use, sleep deprivation, or trauma, but new risk factors emerge all the time. Researchers recently confirmed that cannabis use can spark a psychotic episode. It seems likely that chatbots might be a new risk factor, but psychiatrist Joe Pierre also warns against jumping to conclusions, as psychosis can manifest in odd contexts — even hot yoga. He once treated a person whose episode was associated with a dayslong yoga retreat, but he pegs the patient’s sleep deprivation, not their meditation, as the causal mechanism. Something similar might be happening with AI-mediated delusions.

“If you weren’t immersed, and you weren’t using [the chatbots] in this fashion where you weren’t eating, you weren’t sleeping, would it carry the same risk? Almost certainly not,” said Pierre, who practices at the University of California, San Francisco, Langley Porter Psychiatric Hospital.

From folie à deux to AI: How machines may reinforce delusional thinking

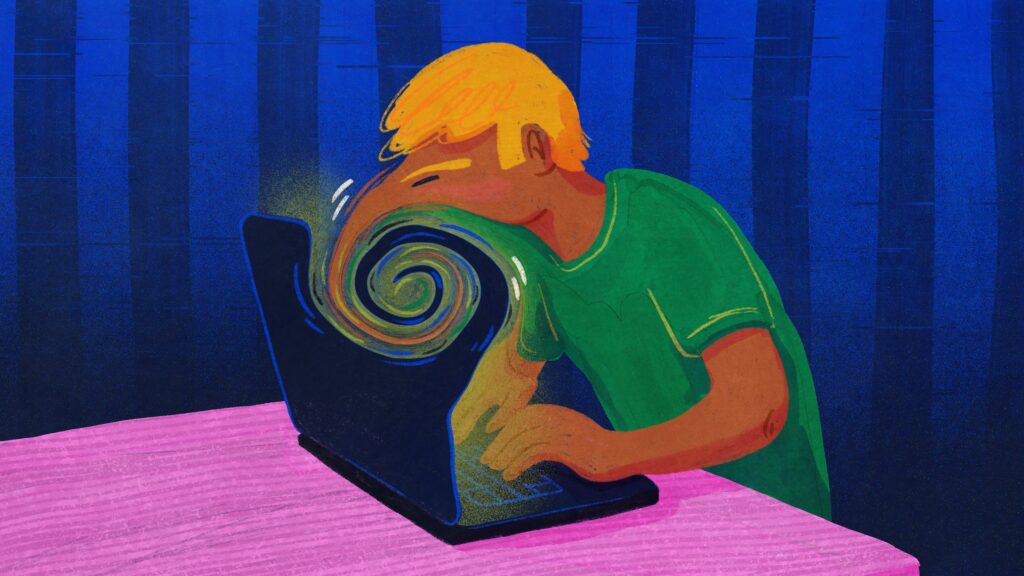

AI-mediated delusions do appear to have unconventional presentations. Delusions are, by definition, almost never shared. But it is undeniable that chatbots are co-creating delusional spirals by mirroring, affirming, and amplifying the user’s statements.

Chatbots are creating thorny ethical questions about transparency in mental health care

Pierre and other clinicians say the chatbot-user relationship resembles a dynamic found in a rare condition that has fallen out of diagnostic vogue: folie à deux, or shared psychosis, in which the strength of one person’s delusions can seemingly infect a loved one and in turn reinforce the initial psychosis.

Chatbot interactions recreate some of this dynamic through their insistent validation, which psychiatrist Hamilton Morrin calls an “intoxicating, incredibly powerful thing” to have if you’re lonely. He said delusional users can also see these machines as deities, which raises a key question that many clinicians are trying to answer: Is this psychosis about AI or is this psychosis spurred by AI?

If a person just believed a piece of technology was a god, then medical professionals have the tools to treat such delusions. But a preprint from Morrin and his colleagues suggests the emerging phenomenon extends further: These chatbots are acting like rocket fuel for delusional thinking. “It’s like pouring gasoline on flame, even if it’s not the initial spark,” said Vasan.

Concerned friends or family members can push back against a person with delusions who insists that, say, Elon Musk has implanted a chip into their brain (a common enough delusion that it was mentioned by multiple clinicians). Chatbots don’t proffer the same resistance, and extended interactions can wrench a person from reality. Each conversational entry in a chat tugs the exchange off course, a mutual reinforcing of delusions that can catapult a person and a chatbot from a normal-seeming setting to a distant, warped truth.

“That’s why people like it, you get to talk to what feels like someone who’s really like you and who gets you,” said Sarma. “And maybe that’s fine most of the time, but in this circumstance, if you are having a mental illness, there’s this risk that you’re pulling it in until what it’s mirroring is a mental illness.”

Finding the moment when the banal turns bizarre

Clinicians are particularly interested in understanding the conversational tipping point when a banal interaction turns bizarre. Quick, short responses don’t seem to reinforce delusional thinking as much as rollicking, several-day-long conversations. Sarma wants to understand how these extended back-and-forths fuel a break from reality. He and his colleagues plan to study how often people with mental illness are using chatbots and how frequently users are exposed to a chatbot validating ideas that aren’t reality-based.

Studying a weeklong conversation is not a breeze. Besides the tedium of analyzing thousands of messages, a chatbot is never frozen in time or place. Not only do they tailor responses to the individual they are communicating with, they also are frequently updated to reflect input from users across the world. The chatbot a scientist engages with or parses the transcript of on Monday can change by Tuesday, which could hamper a researcher’s ability to design a properly controlled study. But figuring out how to replicate chatbot conditions will be crucial for understanding whether AI-mediated delusions can develop into a more chronic condition like schizophrenia.

Other research groups are using a technique called red teaming to test chatbots’ vulnerabilities and safety scripts that chatbots use when they detect mania, psychosis, or suicidality. “When you look at these transcripts that are hundreds of pages, there should have been 100 places where it said, ‘I think you should talk to someone, here’s a number,’” said Vasan, who is also developing relevant treatment guidelines for clinicians.

OpenAI has said it is aware that ChatGPT’s safety scripts — for example, if you’re not doing well, call this hotline — to divert suicidal and psychotic conversational threads break down over the course of a long exchange. On its website, the company says it is forming an advisory group on mental health issues and developing an update to GPT‑5 that will help the bot “de-escalate by grounding the person in reality” and encourage people to take breaks during lengthy chat sessions.

A company representative did not respond when STAT asked for clarification on how the company would institute those safeguards into the code. But without knowing what’s under the hood, researchers say it’s hard to be confident ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, and other chatbots won’t act like catalysts for delusions or other negative mental health outcomes.

“You’re basically then just throwing more ingredients into the pot and seeing what comes out,” said John Torous, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

The lack of AI-mediated delusion cases prior to the spring has some experts wondering whether the phenomenon is merely an artifact of OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4.0. Even if that’s true, Vasan said these companies owe their users transparency. She pointed to a recent article in The Verge in which OpenAI CEO Sam Altman suggested that the percentage of ChatGPT users with unhealthy relationships with the chatbot is “way under 1 percent.” If, as the company claims, the chatbot has 500 million users, the number of people affected is still significant.

‘If any medication was hurting [5 million] people, that company would be dead,” said Vasan. “They would be sued and no one affiliated with that company would ever be able to work in pharma again.”

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org. For TTY users: Use your preferred relay service or dial 711 then 988.

STAT’s coverage of disability issues is supported by grants from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.