Normal text sizeLarger text sizeVery large text size

I am in love with Toni Jordan’s house the moment I enter: climbing the stairs toward her spacious, light-filled lounge, each nook and crevice offers a small army of books. I am half-asleep, having just returned from holiday, and feel I must be dreaming: this is the platonic ideal of a writer’s home.

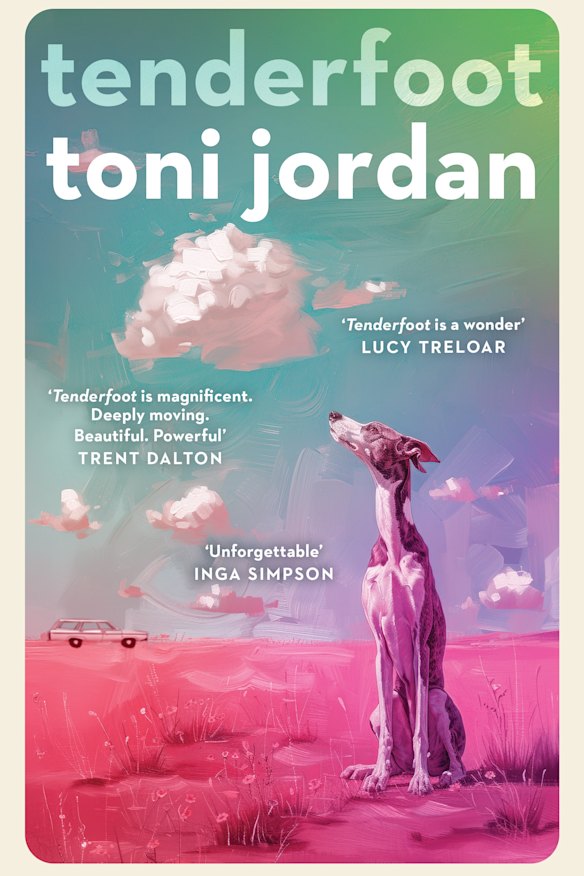

I confess to Jordan that part of the reason I am still asleep is not only jet lag but the fact of having read her incredible new novel, Tenderfoot: it kept me up all night.

“That’s very kind,” she laughs. She speaks in tidy, concentrated bursts that speak to her life as a former scientist (and current practiced interviewee). The process of writing the book, she says, was a “slow burn”.

Melbourne writer Toni Jordan.Credit: Jason South

During the 2018 Sydney Writers’ Festival, Jordan, whose 2012 debut Addition was an international bestseller and was long-listed for the Miles Franklin award, spoke about her mother.

Later, in an ABC interview, she reflected publicly on her family and childhood. It prompted her publisher, Hachette, to ask if she wanted to write something about her life.

“My mum died, a few years ago, in 2018. I couldn’t have written Tenderfoot while she was alive. I don’t know how she would have handled it. She certainly read my novels. I remember when she read Addition, which is in the first person, she said to me, Who’s she talking to, love? And I thought, hang on, who is she talking to? There’s something about first-person fiction that always makes people think it’s you. And this certainly has intersections with my life. It’s different from what I’ve done before.”

Tenderfoot is set during a period of immense change in Australian society. Gough Whitlam is in power, but it is the life of its young narrator, Andie Tanner, in 1970s Queensland that provides the emotional locus of the story. She is a girl struggling with her mother’s separation from her father – a greyhound trainer – and growing up in an insular community during the Joh Bjelke-Petersen years. Andie provided Jordan with a way of accessing the world she wanted to capture: a vanished childhood, a vanished country.

“It’s all about conjuring that feeling up. It’s like method acting. You sit down and you go, today, I’m a 12-year-old girl: what is that like? What am I interested in? I think people underestimate the incredibly rich inner lives children have. I remember vividly those childhood feelings of being utterly powerless, of having no agency over your life. Anything your parents said, it was something you had to do. One of the things I’m so happy about, getting older, is that you have more control over your life.”

Jordan edits as she writes, spending the first hour of her writing looking back over the previous day’s writing. She describes trying to capture the “integrity of memory”. She has never done anything quite “so close, that’s quite so inspired by my own life”.

Jordan’s first degree was in molecular biology. For a long time, she worked as a research protein chemist. The novel’s voice, she says, took a few months to settle on; the chemistry fiction requires, it seems, comes from a different place. She sees writing as less front-brain oriented, akin to performing “little experiments on myself”.

“I’m fundamentally lazy – which is really a superpower, I think. Because I don’t have the energy to stuff around. I played with narrating it in a straight child voice. I played with an adult voice, looking back. And then I tried to make it fluid, sometimes in the same paragraph. I was thinking about books that do that kind of graceful shift in perspective, the way Emma does. That fluidity of the perspective of the voice was the hardest thing.”

Has she ever tried writing with more planning involved?

“Absolutely shit for books! The goal of characters and fiction is to be at once surprising and inevitable,” she says.

Planning, she says, resulted in books that were “stilted and predictable”. Jordan attempted working on two novels according to a plan; she abandoned both. One, she says, she “carved up”, taking bits and using them elsewhere. “The other one’s just too bad,” she says resignedly.

“Sometimes I think, as I go along, books get harder. Because you pick the low-hanging fruit first. Whereas this was really a joyous book to write.”

Jordan as a baby with her mother.Credit: Courtesy of Toni Jordan

It’s surprising to hear; Tenderfoot is often sad (I have a collection of empty bedside tissue boxes to prove it). Its affection for its characters stems, in part, from conveying the powerlessness and emotional opacity of adults. Andie’s own attempts to exert control and to express her feelings put her at a great deal of risk.

“Most of our sadnesses, I think,” Jordan says, “are normal, quiet, human. And control is futile. It’s an illusion to think that we have any at all, really. It’s something I’ve always wrestled with. The more I look over all of my novels, all the way back to Addition, almost every single one is about control.

“It’s something that just keeps coming back. It’s why I still love writing fiction. Because the challenge is to get out of my own way. I’ve got to sit down every day and understand that I’m skiing down a mountain with a blindfold on and give myself over to it. That’s the only way it works.”

As Andie’s adult self looks back and reflects on her childhood, she becomes conscious of the fallibility of memory: how memories can become true by virtue of being repeated and relived until they come to seem true. It’s an apt metaphor, I suggest,for the process of creating fiction: making something that is both entirely real and entirely false at once.

Loading

“I think that’s absolutely right. Memory is something that I’ve always felt doesn’t actually exist. We have an idea that memory is sitting there waiting for us. But really it’s constructed and new every time we demand something of it. And that can change over time. It does change over time.”

Having written a novel that hews so close to her life, does Jordan ever worry about having used up most of her low-hanging fruit?

She smiles archly.

“It’s really interesting that you ask that,” she says. “Because the thing that I’m working on now is a love letter to fiction. I’m trying to resurrect a dead person, reimagining their life. Someone who died but shouldn’t have. It’s doubling down on that idea of the power of fiction. It’s about fiction being the antidote to that tragedy.

“A lot of novels that I’ve read lately, by writers I admire, there’s a feeling that fiction has run its course. I never feel that. It’s the most powerful thing. ”

Toni Jordan’s Tenderfoot (Hachette Australia) is out now.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.