NASA saw a black hole collision, and the consequences of the impact were felt through spacetime at a very high speed – but none of them ceased to exist; they became only one, giant black hole. Since early studies about black holes and their destructive nature have been published, NASA has tried to keep track of multiple cosmic structures, and when something as big as a black hole collision happens, everyone gets a warning – but only a few can detect what’s happening, and the James Webb did.

Black hole collisions don’t affect humans, but we can feel when it happens

Black hole collisions are not new to science, but it is a recent discovery. In 2015, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) identified the first-ever collision in history. While several other events are believed to have taken place before the Earth itself was formed, this one was the first time NASA had identified something like this happening – it was captured by four LIGO instruments in multiple states in the U.S.

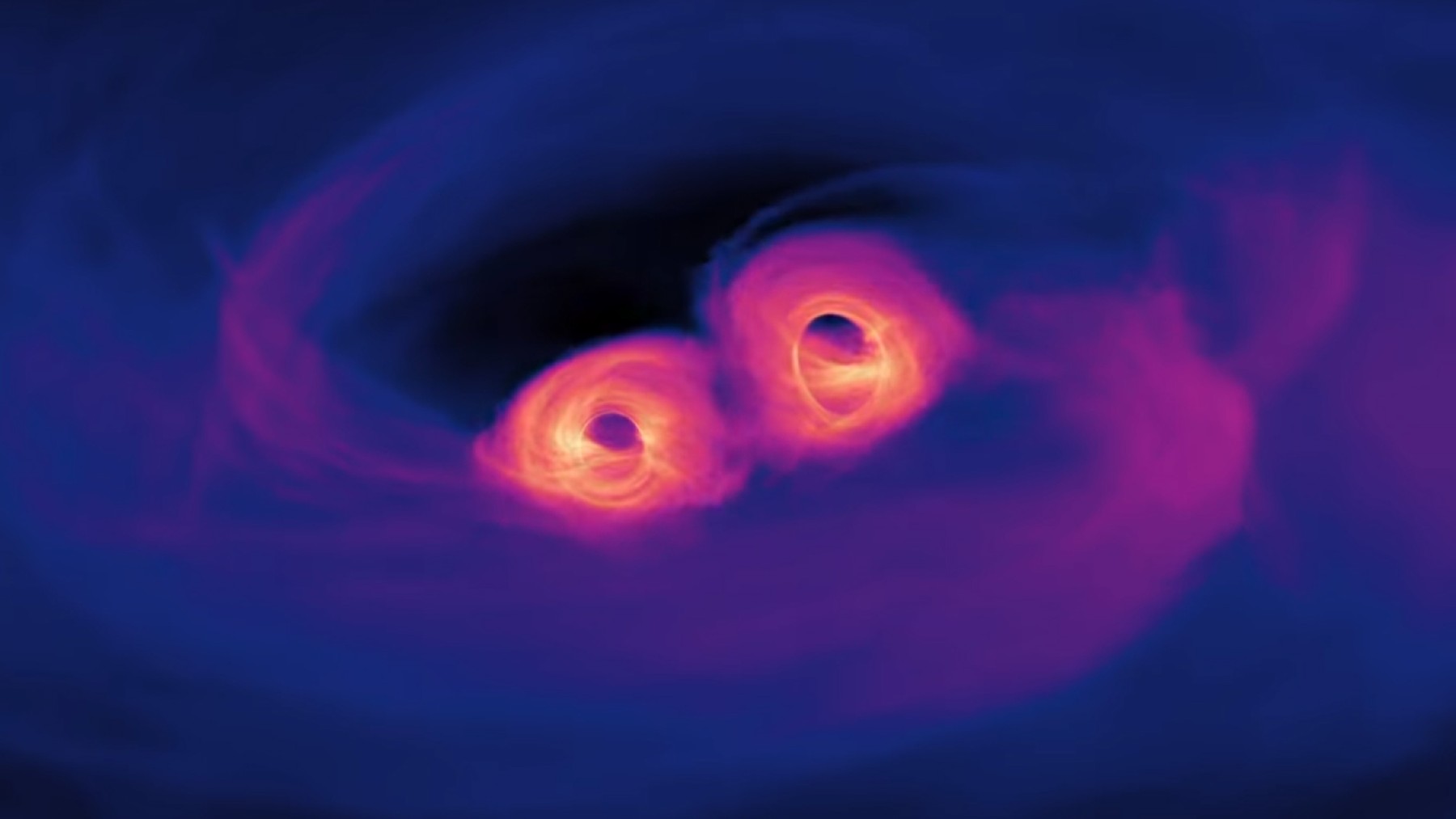

The collision sent waves through the fabric of spacetime, sending a message that something big had happened. These signals came to Earth, something that doesn’t happen often, and NASA had the first glimpse of two black holes colliding. The event involved two cosmic bodies with over 26 to 36 times more mass than our sun, and they were not destroyed in the process – they merged into a bigger one. This is exactly what NASA scientists once again had a glimpse of, but this time the event is so old that most of our universe wasn’t around at the time.

NASA confirmed: Oldest black hole merging in history signaled us

For the first time, astronomers have observed two black holes colliding in the ancient universe, capturing a glimpse of galactic evolution when the cosmos was just 740 million years old—roughly a twentieth of its current age. The James Webb Space Telescope provided these groundbreaking observations, revealing not only the merger of two galaxies but also the immense black holes at their centers.

This discovery suggests that massive black hole mergers were surprisingly common in the early universe, offering a possible explanation for how supermassive black holes, like the one anchoring the Milky Way, grew to such enormous sizes. Previous theories speculated that these cosmic giants either consumed matter at extraordinary rates or were born unusually large. The new evidence points to a third option: rapid growth through multiple black hole collisions.

The leftovers of the merger: Two monsters became one, a supermassive black hole

Until now, it remained uncertain whether merging galaxies would inevitably cause their central black holes to combine into a single massive entity. Some theoretical models had suggested that one of the black holes might be ejected into space, becoming a “wandering black hole.” Webb’s observations, however, reveal that the merger process can indeed produce a unified, supermassive black hole.

During the black hole collision, the cosmic bodies devour immense amounts of matter and release extraordinary energy. This activity leaves distinctive spectral signatures, which allowed astronomers to identify the merger in a system known as ZS7. In this system, one of the black holes has a mass estimated at 50 million times that of the Sun.

The event could have impacted the formation of the universe

Further analysis of black holes from this period indicates that roughly a third were undergoing similar mergers, suggesting that the black hole collision may have played a major role in the early growth of these cosmic titans. Researchers see this as a critical clue in understanding how the first supermassive black holes formed and evolved. The findings from this Webb telescope study were published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.