The James Webb Space Telescope has already opened a window to the early universe—but its gaze also extends closer to home. In early 2025, it gave astronomers an unexpected gift: a brand-new moon hiding in the shadows of Uranus.

Centuries after the planet’s discovery, the James Webb telescope is still helping scientists deepen our understanding of the outer Solar System—and revive stories of the early pioneers who once mapped the skies with telescopes and math alone.

Have you heard of Anders Lexell? The Swedish-Finnish mathematician and astronomer moved to Russia in 1768 and befriended Leonhard Euler. Lexell was the first to calculate the orbit of Uranus after William Herschel spotted it by chance in 1781.

At first, Herschel thought he’d found a comet. But Lexell’s calculations changed everything—proving this was a new planet. He even noticed gravitational disturbances suggesting yet another planet was out there (spoiler: it was Neptune, though it wouldn’t be officially discovered until 1846).

Two centuries after Lexell and Herschel

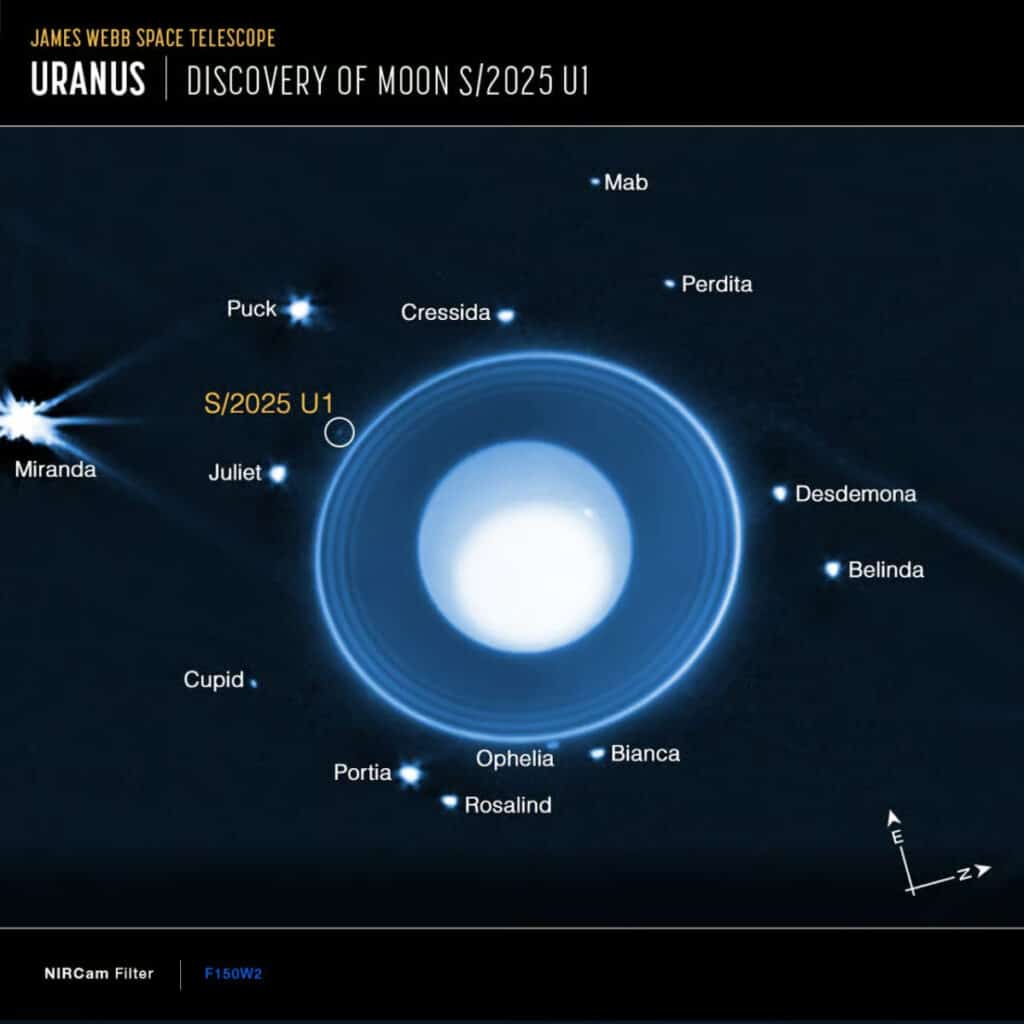

In 2025, NASA and ESA revealed that a new inner moon had been spotted orbiting Uranus—one that had escaped Voyager 2’s flyby nearly 40 years earlier. The discovery was made by a team at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) using JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera.

A presentation of Uranus and its many peculiarities. © National Geographic

“It’s just 10 kilometers wide,” said Maryame El Moutamid, lead scientist on the project. “We found it in ten 40-minute long-exposure images. It’s small, but a huge find—even Voyager missed it.”

S/2025 U 1 — or something more poetic?

Matthew Tiscareno from the SETI Institute emphasized how unusual Uranus is. “No planet has more small inner moons. Their chaotic interactions with the planet’s rings blur the line between what counts as a moon and what’s part of the ring system.”

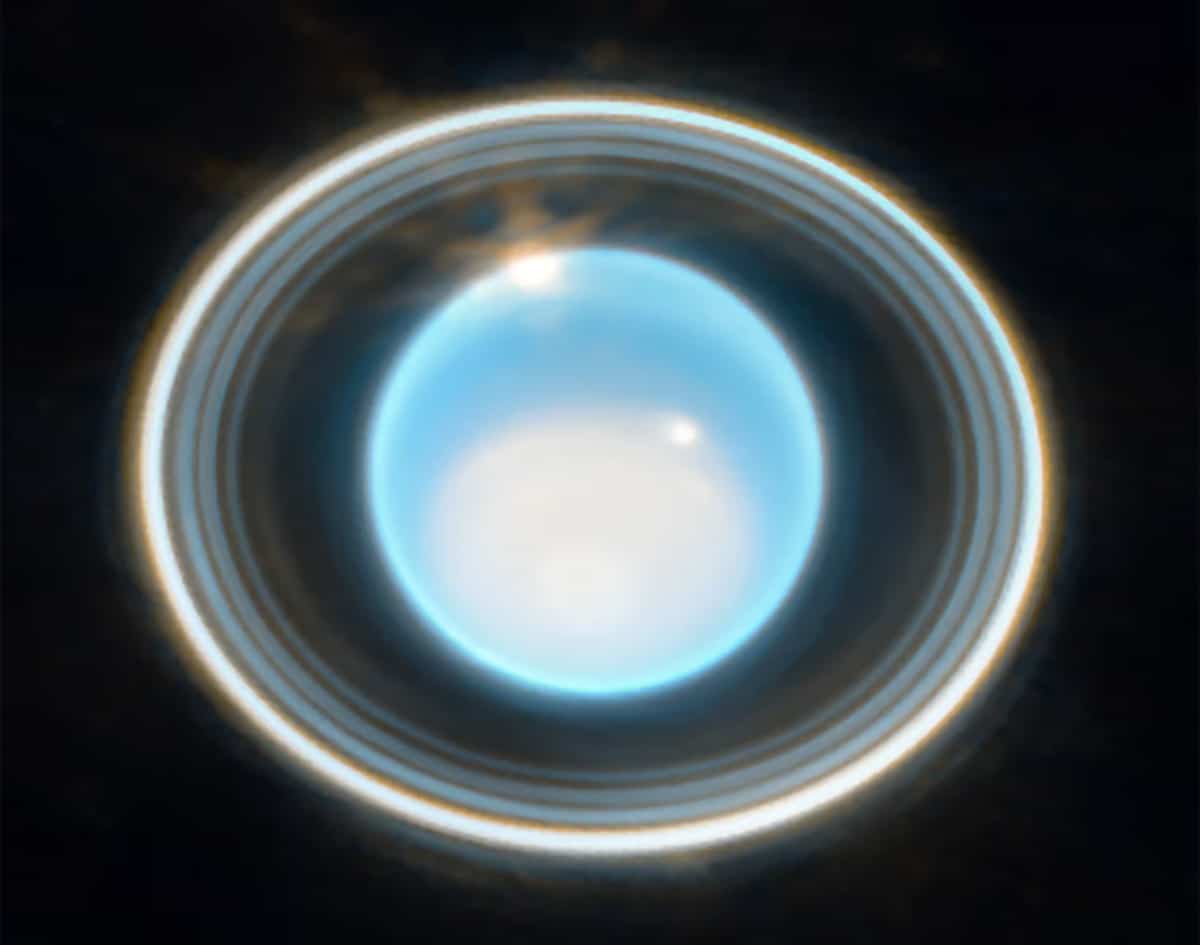

Uranus, its rings and its satellites captured by the James Webb telescope. © NASA, ESA, University of Idaho

This new moon is even fainter and smaller than Uranus’s tiniest known satellites. It orbits 56,000 kilometers from the planet’s center—between Ophelia and Bianca—and follows a nearly circular path, suggesting it formed right where it is.

Like its siblings Miranda, Ariel, Titania, and Oberon, this moon will eventually get a name inspired by characters from Shakespeare or Alexander Pope. For now, it’s called S/2025 U 1. The final name will be approved by the International Astronomical Union.

A notebook, a king, and a name

William Herschel’s original discovery notes from March 1781 describe Uranus as “a curious nebulous star or perhaps a comet” near Pollux. Further observations revealed what no one had seen in millennia: the first planet discovered in modern history.

Herschel wanted to name it Georgium Sidus in honor of King George III. The name made him popular with the crown—but not with the rest of Europe. Eventually, the world agreed to name the planet Uranus.

The Royal Astronomical Society Library and Archives contains books, images, and documents important to the development of scientific thought in astronomy, geophysics, and related disciplines. In this video series, RAS Librarian Jenny Higham showcases some of the gems in the collection. © Royal Astronomical Society

More than 240 years later, the story of Uranus continues to evolve. From Herschel’s telescope to Voyager’s flyby to the cutting-edge eyes of James Webb, this icy world still holds secrets—some no wider than a city, and others yet to be seen.

Laurent Sacco

Journalist

Born in Vichy in 1969, I grew up during the Apollo era, inspired by space exploration, nuclear energy, and major scientific discoveries. Early on, I developed a passion for quantum physics, relativity, and epistemology, influenced by thinkers like Russell, Popper, and Teilhard de Chardin, as well as scientists such as Paul Davies and Haroun Tazieff.

I studied particle physics at Blaise-Pascal University in Clermont-Ferrand, with a parallel interest in geosciences and paleontology, where I later worked on fossil reconstructions. Curious and multidisciplinary, I joined Futura to write about quantum theory, black holes, cosmology, and astrophysics, while continuing to explore topics like exobiology, volcanology, mathematics, and energy issues.

I’ve interviewed renowned scientists such as Françoise Combes, Abhay Ashtekar, and Aurélien Barrau, and completed advanced courses in astrophysics at the Paris and Côte d’Azur Observatories. Since 2024, I’ve served on the scientific committee of the Cosmos prize. I also remain deeply connected to the Russian and Ukrainian scientific traditions, which shaped my early academic learning.