Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection is a novel-in-stories about people fluent in failure — not the kind you overcome, but the kind that folds into your posture, shapes your voice, and acts as proof of having tried; not to be exceptional, but to avoid being a failure — only to fail anyway. These hyper-articulate, painfully self-aware people, fluent in guilt, shame, theory, and therapy, come together to form a book that is fiercely intelligent, emotionally precise, and painfully, sometimes hilariously, accurate.

Tony Tulathimutte’s subject is the chronically online, over-educated, and under-fulfilled children of the 21st century. (Shutterstock)

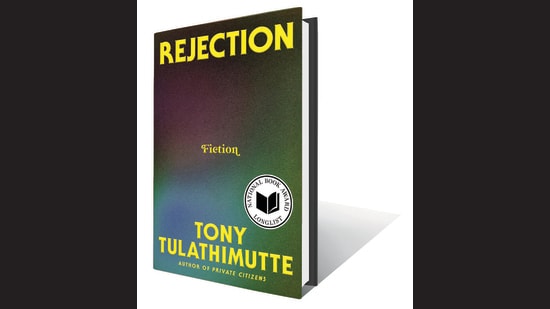

Tony Tulathimutte’s subject is the chronically online, over-educated, and under-fulfilled children of the 21st century. (Shutterstock)  240pp, ₹798; HarperCollins

240pp, ₹798; HarperCollins

Jane Austen dismantled marriage plots, Charles Dickens tore into the ugly side of the Industrial Revolution, and Tolstoy questioned everything from religion to romantic ideals. Woolf, Orwell, Huxley, and Hemingway each held up a mirror to a world cracked by war, modernity, and the ego. In Rejection, Tony Tulathimutte takes up that mirror and turns it towards a new literary underclass: the chronically online, over-educated, and under-fulfilled children of the 21st century. What stares back is brutal, messy, hilarious, and disturbingly familiar.

The book opens with The Feminist, the story of a self-declared, hyper-aware male feminist who prides himself on allyship. But his belief in his own goodness — his performance of accountability — quickly curdles under the weight of rejection. First published in n+1 to acclaim, the story charts his slow descent from a politically correct ally to a bitter, self-pitying misogynist, the kind who spends his days moderating obscure online forums. In razor-sharp prose, Tulathimutte peels back the layers of well-meaning male feminism to reveal how easily it can collapse into narcissism, entitlement, and resentment when it fails to deliver emotional or romantic returns.

Rejection runs through the book, not just as a plot point but as a diagnosis of the modern psyche. Pics follows the spiral of a white woman after being rejected by a friend-turned-one-night-stand. “Love is not an accomplishment, yet to lack it still somehow feels like a failure,” Tulathimutte writes, exploring the hunger for validation from someone she doesn’t even like. As with all of his characters, she is caught in the grind of overexposure — trapped between the dopamine rush of constant content consumption and the exhausting need to perform empathy, understanding, and progressiveness for an ever-watching world.

But rejection, in Tulathimutte’s world, isn’t just limited to the heart. In Ahegao or The Ballad of Sexual Repression, we meet Kant, a Thai-American man who believes he’s grappling with his sexuality only to realise that the actual source of discomfort in his life lies in his kinks. His story captures the tension between private desire and public performance — his need to live out his fantasies while appeasing social norms. Once again, rejection looms: romantic, social, and most importantly, internal.

In Our Dope Future, Tulathimutte turns his gaze to a business dude-bro obsessed with podcasts, optimisation and startups. Blinded by hustle culture and inflated ambition, he loses sight of what a relationship even means. Rendered in pitch perfect Gen-Z lingo, the story shows how for some, love has become another inefficiency to fix.

The centrepiece of Rejection is Main Character, a story of a gender-fluid person trying to hide from the real and online world. Taking up the majority of the book, it talks about how the online environment breeds narcissism, bigotry and ideological rot — thereby allowing people with hateful intentions to proliferate due to easily accessible anonymity. It raises questions about the legitimacy of everything we see online, critiques the open plagiarism and theft of ideas.

Tulathimutte’s writing is sharp and makes pointed jabs at the fallacy of contemporary internet culture. It illuminates the struggles faced by today’s youth in a politically, socially, and technologically volatile world. Rejection captures the growing divide between people who are ever connected to each other. “Shrieking into the void is more fun when you’re also someone else’s void,” writes Tulathimutte while discussing the echo chambers of Twitter (now X).

The tone of the book is a rare mix of erudition and “shitposting” energy — equal parts theory and online slang. Sentences like “Twitter was the right word for it, birdsong being a Darwinian squall mistake for idle chatter, screaming for territory and mates” live alongside “A crowded elevator where anyone who smelled a fart also had to fart.” Rejection reads a dissertation and a chaotic group chat at once — and it works because Tulathimutte never loses control. He understands that absurdity is not the opposite of intelligence, but its unexpected partner.

While the stories are loosely linked by the theme of rejection, it’s the subtle crossovers — characters slipping into the margins of others’ lives — that keeps the reader engaged. Everyone is echoing everyone else, knowingly or not.

If there is a gripe, it is that after a point, the precision becomes too much. Seeing yourself — your worst habits, your most concealed vanities — reflected back at you with such clarity can feel less like recognition and more like an autopsy. The fatigue creeps in. And perhaps that’s the point. Tulathimutte doesn’t offer catharsis or redemption; he offers exposure. Still, this unrelenting sharpness may alienate some readers — not everyone wants to be dissected that precisely.

Author Tony Tulathimutte (Clayton Cubitt/NewYorkStateWritersInstitute)

Author Tony Tulathimutte (Clayton Cubitt/NewYorkStateWritersInstitute)

Despite the slump in the latter half, Rejection redeems itself with a clever closing. It captures the book’s essence and flips it on its head — critiquing its own flaws and self-indulgence with a sophistication that, in itself, reads as yet another layer of satire.

In the end, Rejection doesn’t diagnose our condition — it embodies it. The performance, the paralysis, the yearning for sincerity and love under layers of irony: it’s all there. If Rejection reads like the funniest novel you’ve read in years, your mind hasn’t been corroded by endless cycles of doomscrolling. But if it feels like your own life laid bare, then it’s time to wake up. It’s not too late.

Rutvik Bhandari is an independent writer. He lives in Pune. He is a reader and a content creator. You can find him talking about books on Instagram and YouTube (@themindlessmess).