If you’ve followed the career of Lena Dunham and read some of her most poignant writing for this magazine, you’re likely aware that she’s not afraid to bare her personal struggles – with relationships, with health, with extra-long nails. An ability to combine profound reflection with insight, grit and humour is one of the hallmarks of the director, actor and writer’s non-fiction work. “My nurse,” she wrote in an essay about her hysterectomy for Vogue, “is a model-gorgeous woman, sardonic and odd, like the sidekick on a TV show who producers pretend is less stunning by slapping spectacles on her.”

This spring, 10 years after the release of her best-selling memoir Not That Kind of Girl, she will publish her second book, Famesick, a nonfiction work about how health troubles have intersected with her life in the spotlight. “I felt a little bit like the detective in the movie who has the newspaper clippings and the red strings,” she tells me of the process of writing the book, which involved going back into her emails and diaries, “trying to put it together and understand exactly what had happened and how it had happened and why it had happened.”

Of course, the book is not just a medical mystery; it’s also a study of ambition, the desire to please – especially as a young woman – and what happens when those impulses run up against physical limits. Dunham first found success at just 23 years old, when her debut feature, Tiny Furniture, was released in 2010; Girls would follow in 2012. At the same time, her health struggles (coupled with substance abuse issues) were compounding.

It was hard to hit pause on all her obligations and desires, she says: Writing for film and television was her “version of going to the Olympics – it doesn’t matter if you have a cold, it’s the Olympics.” The breakthrough finally came when, as she puts it, “the override function stopped, and I was no longer able to do the suppression that was required to participate in daily life.”

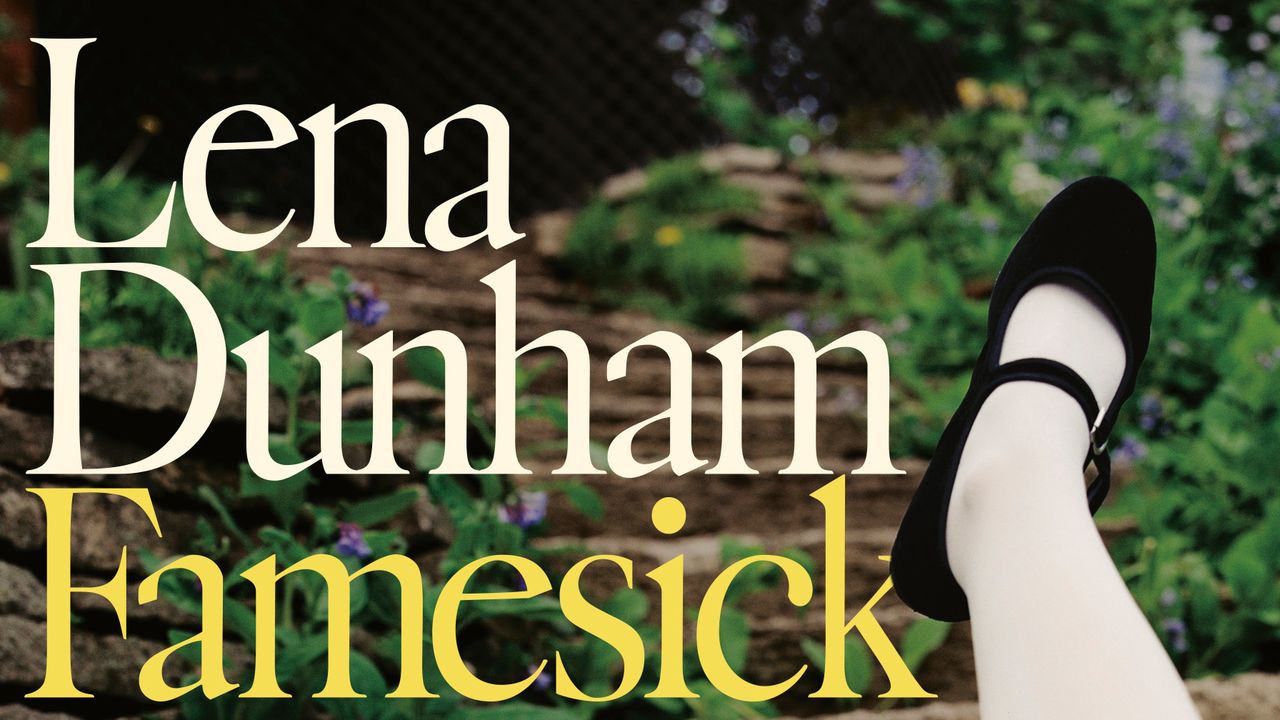

The year 2018, she says now, was “the year that did not exist,” as though she had stepped “through the looking glass” into an alternate reality. “You start to feel like, I’m no longer in the land of the living, and will I ever get to go back there?” (Not coincidentally, the image on her new book’s cover – a photo by Anna Gaskell that Dunham has loved for years – is a reference to Alice in Wonderland.)

Dunham feared that airing what was happening would lead people to perceive her as something of a liability: “We live in, for lack of a better word, an ableist, capitalist world, where your ability to produce is so connected to the idea of your worth.” Now, she says, she has come around to the idea that “honestly expressing how hard things have gotten, and then the fact that you moved through and beyond them, makes you actually the opposite of a liability.” She also took comfort –and inspiration – from writers who have contributed to the broader canon of work in this genre, like Leslie Jamison, Melissa Febos, TV producer Barbara Gordon – who wrote the best-selling memoir I’m Dancing as Fast as I Can – and Joan Didion (particularly Blue Nights).