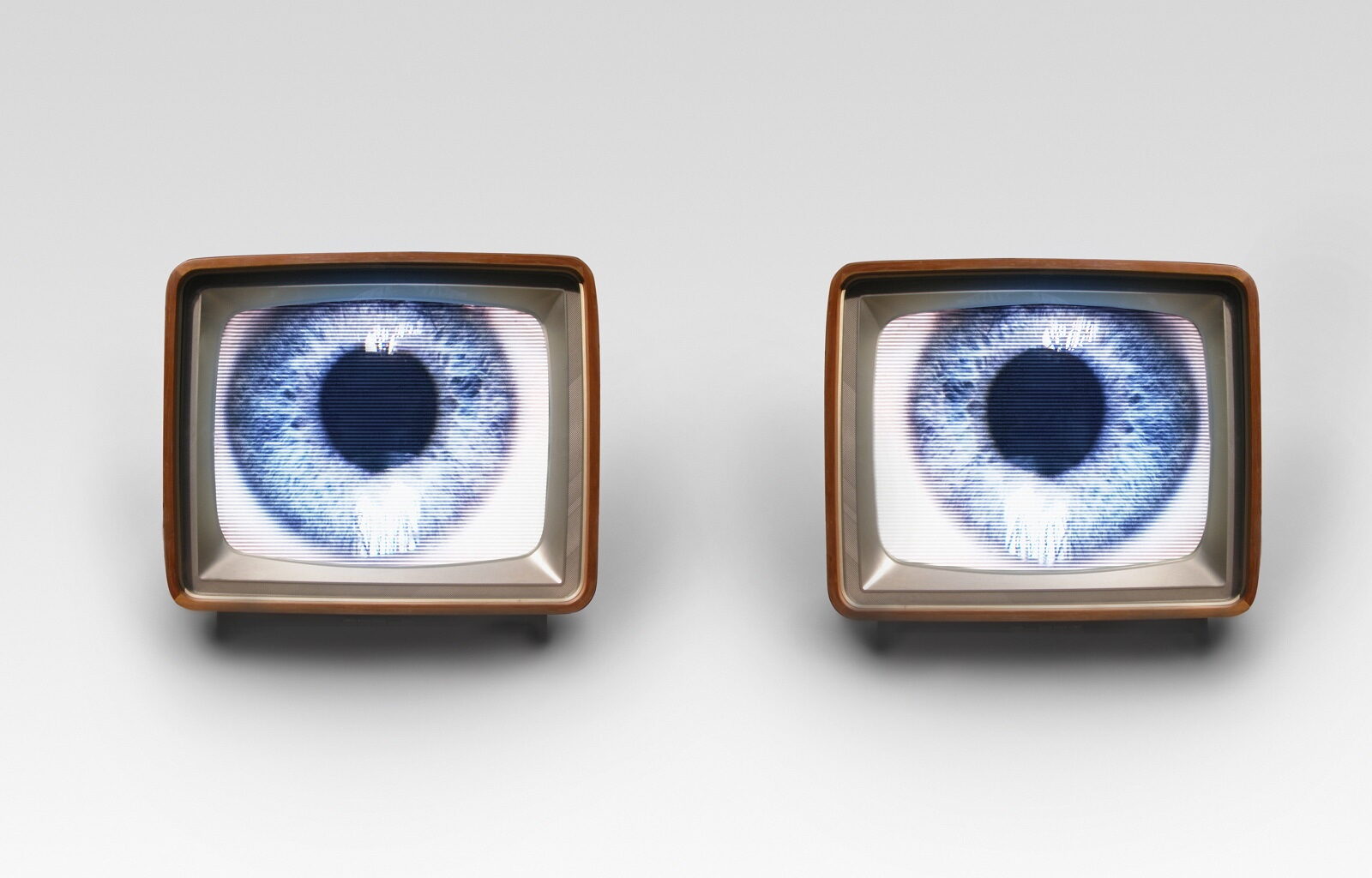

Democracies have been quick to condemn Beijing and Moscow’s digital authoritarianism. But what happens when they begin to adopt the very same tools themselves?

The answer is not that they suddenly stop being democracies. Elections are still held, parliaments still sit, and courts still function. Yet authoritarian methods creep into digital spheres: shutdowns, spyware, and platform bans narrow debate and silence critics. Democracies begin to resemble the regimes they claim to oppose. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in particular lowers the cost and raises the appeal of digital controls, making it easier for governments, even well-intentioned ones, to suppress speech in the name of security.

India and Türkiye illustrate the drift towards digital authoritarianism. Each has adopted digital tools once associated largely with authoritarian states. Taken together, they reveal how democracies can hollow themselves out from within, their openness eroded not by coups or crackdowns, but by the quiet spread of authoritarian practices online.

Long praised as the world’s largest democracy, over the past decade India has become the global leader in internet shutdowns.

For Australia, there is a clear lesson. Vigilance is required not only against authoritarian regimes that deploy digital tools to interfere in politics, spread disinformation, and weaken democratic institutions, but also against the temptations within democracies themselves.

India is one of the most patent examples. Long praised as the world’s largest democracy, over the past decade India has become the global leader in internet shutdowns, most notoriously in Kashmir. The government justifies these blackouts as necessary for the maintenance of public order and protection of national security.

Social media platforms such as Twitter/X and Meta have been pressed to remove posts critical of government policies, including during the 2020–21 farmers’ protests and the Covid-19 pandemic. There is evidence that Pegasus spyware was deployed by the government against journalists, activists, opposition politicians, and even government officials.

Social media platforms such as Twitter/X and Meta have been pressed to remove posts critical of government policies (Camilo Jimenez/Unsplash)

In addition, pro-government supporters have coordinated online harassment of journalists, academics, and opposition figures. Organised trolling campaigns create fear and encourage self-censorship, forcing critical voices to retreat from public debate, and leaving government narratives dominant. The result is a digital environment that is beginning to resemble that of an authoritarian state, and where dissent is often silenced and surveillance pervasive.

Courts as censors

Türkiye shows how democratic institutions can be weaponised to legitimise digital control. In early 2025, Türkiye became the first country to ban AI-generated content. This was only the latest step in a decade-long tightening of online restrictions.

Between 2013 and 2018, more than 20,000 legal cases were launched against citizens for their social media posts, many resulting in prosecutions and arrests. The ruling Justice and Development Party has also cultivated a climate of digital intimidation, with party-affiliated trolls and bots harassing journalists, artists and academics critical of the government. Critics have called this a culture of “digital lynching”.

Opposition politicians are not beyond the reach of Türkiye’s government and judiciary. For example, Istanbul’s mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu has faced prosecutions and account suspensions. Regarded as President Erdoğan’s main challenger, İmamoğlu is now unable to communicate with his 9.7 million followers on X inside Türkiye, even though his account remains viewable abroad.

Under Türkiye’s Internet Law, digital platforms that resist takedown requests face crippling fines or throttling, forcing them into compliance. The effect is an online environment where criticism of the government is suppressed, through the steady application of law, bureaucracy, and intimidation.

Authoritarian drift

These cases differ in context but together show democracies adopting tactics once seen as the hallmark of authoritarian states. The justifications vary, but the result in each case is a narrowing of online debate, silencing of dissent, and normalisation of surveillance.

AI accelerates this drift. Once seen as liberating, AI is increasingly harnessed for censorship, monitoring, and manipulation. Algorithms amplify ruling-party narratives, spyware silences critics, and predictive tools track dissent. Democracies do not need to formally abandon elections or institutions to erode openness: they can do so quietly, through the normalisation of digital authoritarian practices.

A warning for Australia

Australia has rightly invested in countering authoritarian states’ digital operations, from Russian disinformation campaigns to Chinese cyber intrusions. But the risk is not only external. In moments of crisis, democracies often find internet shutdowns, platform bans, or enhanced surveillance tempting. Once such measures are used, they are easily repeated and normalised.

Australia has already introduced expansive metadata retention and online safety laws, while debates continue over platform regulation and misinformation. These measures are not inherently authoritarian. But without transparency and oversight, they risk laying the groundwork for more intrusive control.

If Australia is serious about defending democracy abroad, it must also safeguard democratic practice at home. That means ensuring transparency around surveillance powers, protecting online speech, and resisting the urge to over-regulate platforms. Above all, it requires recognising that authoritarian methods can creep in quietly, under the guise of protecting the public or national security.

The line between open and closed societies is no longer defined solely by geography. The threat comes not only from Beijing or Moscow but from the normalisation of authoritarian methods within democracies themselves.