Found deep in a cave hidden beneath Australia’s arid Nullarbor plain, a new species of kangaroo-like mammal has been described for the first time by a Curtin University-led research team. There are reports of these once-common small marsupials right up until the 1960s, but they became exceedingly scarce once foxes started killing off the native wildlife.

Back then, the little bettong (Bettongia haoucharae) wasn’t known to be a separate species. That discovery was only revealed today in the journal Zootaxa, and in a sad twist, it was coupled with the news that the species is almost certainly extinct.

All that’s been found of the little bettong in recent years are its mummified remains and bones. Lead author Jake Newman-Martin only realised they belonged to a unique species after studying its teeth and limbs during his PhD study of Australia’s bettong species.

The inside of the caves is moist, while above ground it’s hot and windy. Source: Jake Newman-Martin

Surprising reason little bettong bones were preserved

Newman-Martin describes walking across the extinct animal’s former homeland as an “eerie” experience. “Above the Nullabor, there’s nothing around, it’s hot and windy,” he told Yahoo News.

Then, when you enter the Horseshoe Cave, where the little bettong’s remains have been collected, it feels as if you’ve entered an air-conditioned room. “You can feel the air blowing out of the cave, because there’s a whole system of them attached underground,” Newman-Martin said.

The mummified remains of an extinct little bettong. Source: Zootaxa

Had it not been for the caves, the little bettong could have been wiped away without a trace. But its bones have been left on its floor by predatory owls, which once favoured them as a food source.

“The owls regurgitate the bones into what are called pellets, and over thousands of years, they build up. So these cave floors are covered in the bones of small mammals, birds and reptiles. It’s not really sand or rocks, it’s just bones everywhere in all directions,” Newman-Martin said.

“There’s an accumulation of species. You pick up something and know it could be from a species that’s not with us anymore. It’s astounding. It blows you away.”

Incredible discovery could help rare species avoid extinction

Australia has the worst record of mammalian extinction in the world, and this discovery only cements this sad distinction. But the Curtin University-led research hasn’t only revealed new information about the dead, they’ve made an extraordinary discovery about a rare animal, the woylie, that could help prevent it from being wiped out.

By examining the jawbones of critically endangered brush-tailed bettongs (also known as the woylie), they have found two distinct subspecies, the forest woylie (Bettongia ogilbyi sylvatica) and the scrub woylie (Bettongia ogilbyi ogilbyi).

A woylie hopping after it was translocated. Source: Brad Leue

Identifying this distinction is important because woylies are being moved all around the country to try and create new populations and prevent its extinction. And putting a subspecies into a new environment where its teeth haven’t adapted to eat the vegetation could be detrimental to its survival.

“There’s only about 12,000 woylies left in the world, and about 4,000 individuals have been translocated. That’s not to say it’s a bad thing, but we need to be careful or we are potentially sacrificing a critically endangered species,” Newman-Martin said.

Loss of woylies impacts wider ecosystem

Woylies are important to the environment and are considered ecosystem engineers. They’re constantly digging, looking for fungi, roots and invertebrates to eat, and this foraging is essential for spreading seeds and spores around.

When they’re lost from an ecosystem, it begins to decay, so translocating woylies is considered important not only for the species but the wider environment.

The Curtin University-led bettong research was a collaboration with the Western Australian Museum and Murdoch University. This work involved examining 193 bettongs held in collections in Australia and England.

Their work indicates we’re just scratching the surface when it comes to understanding the small mammals that have vanished from Australia’s deserts. They also found what was thought to be two subspecies of woylie, the living Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi and extinct Bettongia penicillata penicillata were actually completely separate species.

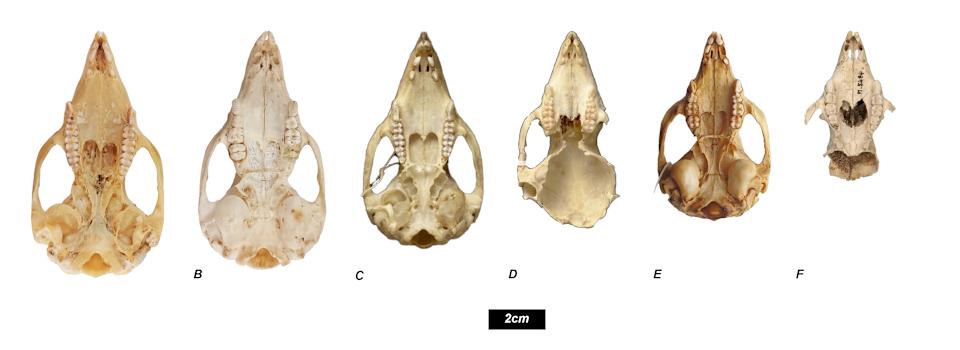

Skulls of bettong from the Curtin University investigation: A) Bettongia ogilbyi sylvatica, B) Bettongia ogilbyi odontoploica, C) Bettongia penicillata, D) Bettongia ogilbyi ogilbyi, E) Bettongia haoucharae, and F) Bettongia ogilbyi francisca. Source: Zootaxa

How deserts have changed since European settlement

For Newman-Martin, it’s heartbreaking to imagine what Australia has lost. Its arid zones were once teeming with small marsupials, like bettongs, bandicoots, bilbies and possums, and today they only survive in small colonies, often in fenced-off sanctuaries to keep them safe from foxes and cats.

“You read journals from people in the 1800s, when they visited these sites, they would have campfires going, and bandicoots would be coming up to the campfire. They were abundant, like rats,” he said.

“You go out there, now, it’s just empty. It’s almost devoid of life.”

An artist’s impression of the little bettong. Source: Nellie Pease

Love Australia’s weird and wonderful environment? 🐊🦘😳 Get our new newsletter showcasing the week’s best stories.