The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) on Wednesday released the national accounts for Q2 2025, which revealed stronger-than-expected growth.

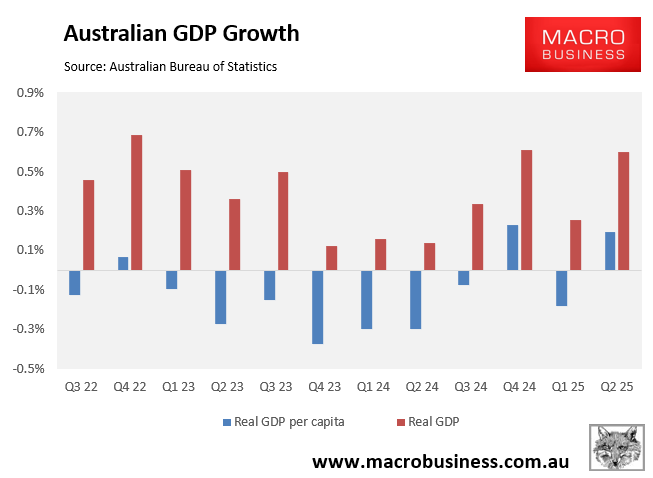

Analysts had tipped a 0.4% rise in headline GDP, and the RBA had forecast 0.5% growth. However, a 0.6% rise was recorded, led by household spending.

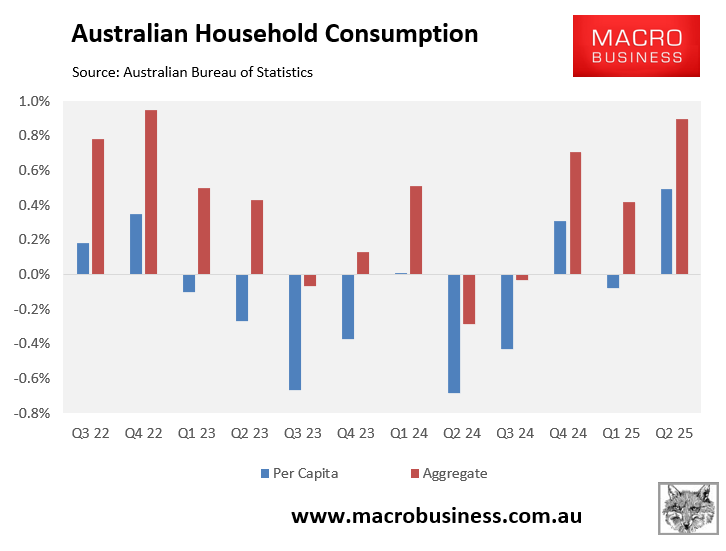

Household spending per capita rose by 0.5% in Q2, the strongest rise in three years. Over the year, per-person spending growth was in positive territory (+0.3%) for the first time in two years.

Advertisement

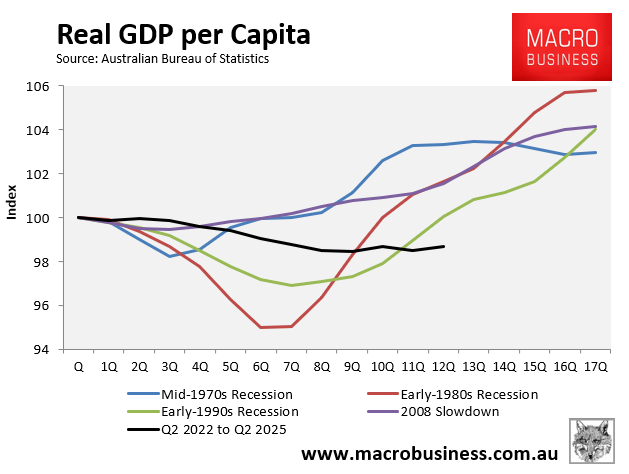

The long, grinding per capita recession ended with a 0.2% rise in GDP per capita in Q2 and a 0.2% increase year-on-year.

GDP per capita recorded only its third quarterly rise in 12 quarters in Q2 25. Over the year, GDP per capita also rose by 0.2%.

Advertisement

Despite the lift, GDP per capita is sitting 1.3% below where it was when the Albanese government came to office in Q2 22.

The lift in per capita household spending and GDP suggests that consumers have responded positively to the RBA’s rate cuts, alongside last year’s Stage 3 tax cuts.

Advertisement

Household consumption should continue to firm as rates are cut, house prices rise, and real wages slowly recover after suffering their biggest decline on record.

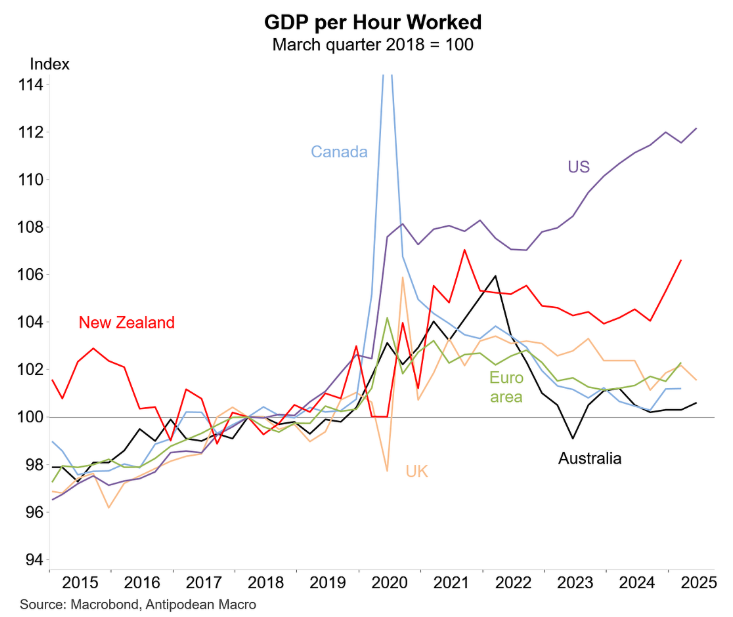

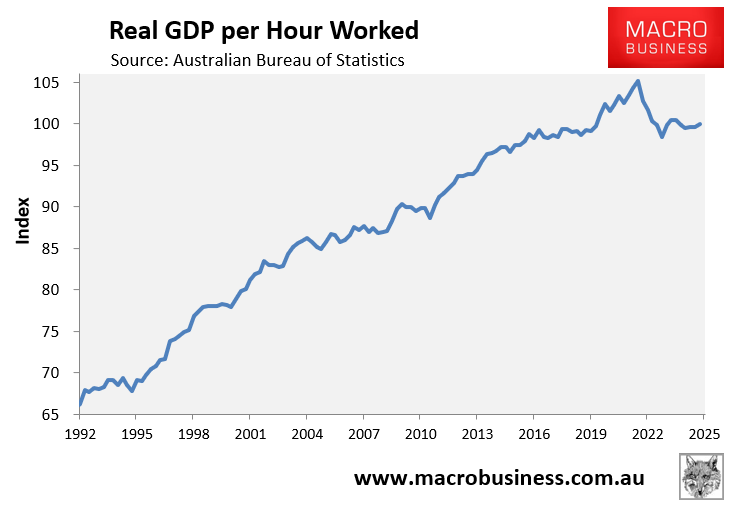

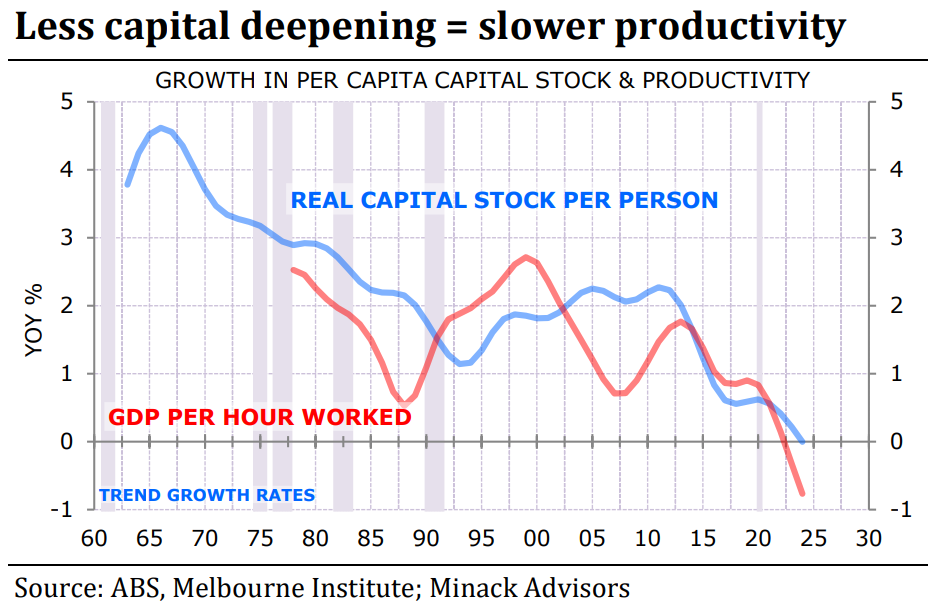

But Australia’s productivity growth remains stillborn:

The increase in GDP, while positive, obscures a larger issue confronting the Australian economy.

Advertisement

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, since 2018, Australia’s productivity growth has trailed below that of other advanced nations.

Wednesday’s Q2 national accounts showed that Australia’s productivity remains stagnant.

Advertisement

Labour productivity in the Australian economy grew by 0.1% annually in Q2 2025. This was the first quarter in a year when the annual rate of productivity growth has increased rather than decreased.

However, labour productivity remained significantly below both Australia’s historical productivity growth rate (1.0% p.a.), and the RBA’s most recent estimate of the economy’s underlying productivity potential (0.7% p.a.).

Advertisement

As shown above, Australia’s labour productivity has barely increased in nine years.

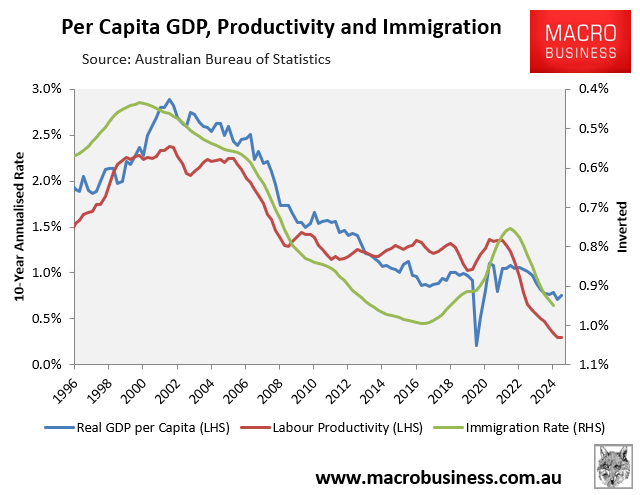

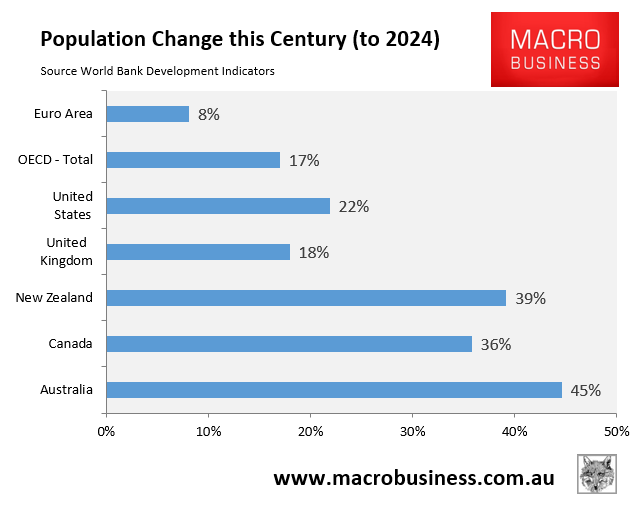

The structural fall in Australia’s productivity and per capita GDP growth has been fueled in part by excessive immigration.

Advertisement

There are two dimensions to this issue.

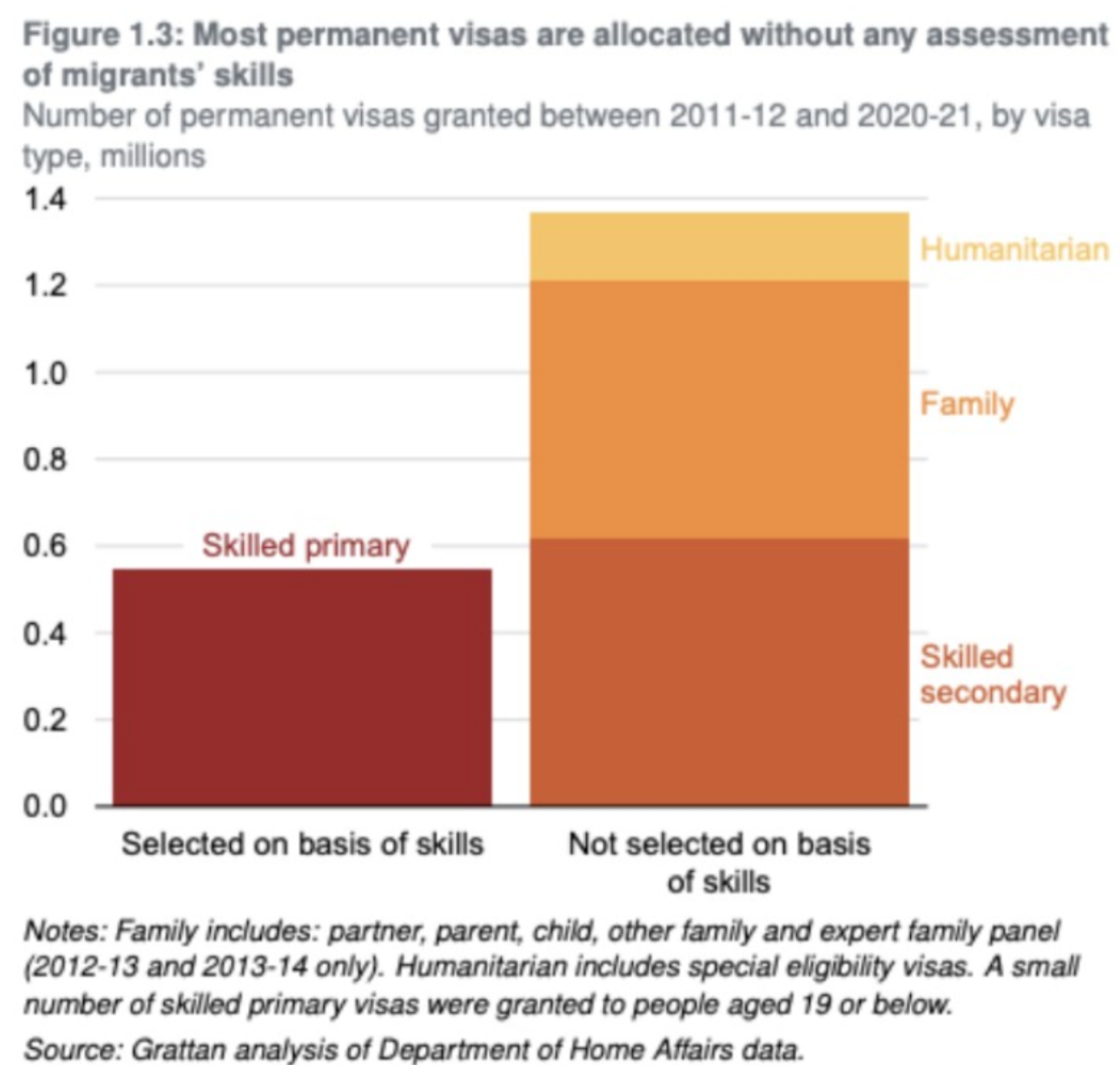

First, the vast majority of migrants arriving in Australia are unskilled. As a result, they reduce overall productivity.

Over half of the so-called skilled migrants who enter the permanent migration program are secondary visa holders (partners of skilled migrants). As a result, they are not assessed according to the skills they bring.

Advertisement

Many purportedly skilled migrants do not work in their fields of expertise and are underemployed in unskilled positions.

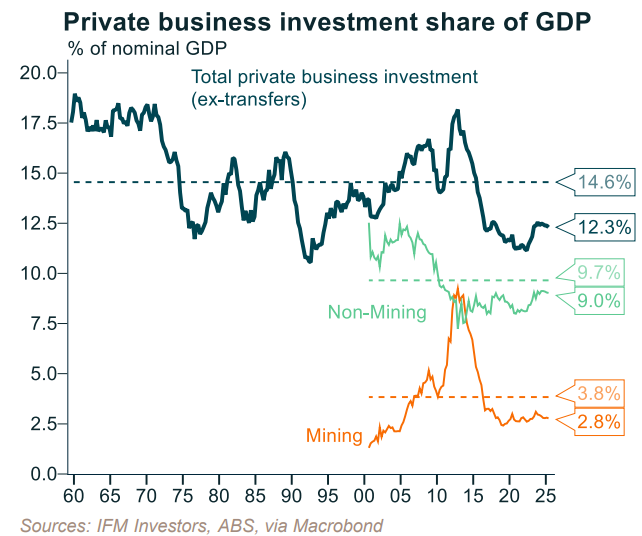

Second, Australia’s population has outpaced business, infrastructure, and housing investment, resulting in ‘capital shallowing’.

Advertisement

Australia has failed to equip the millions of additional migrant workers with the necessary tools, machinery, and technology, as well as provide enough dwellings and infrastructure for the millions of additional families.

As a result, everyone’s standard of living has decreased.

Advertisement

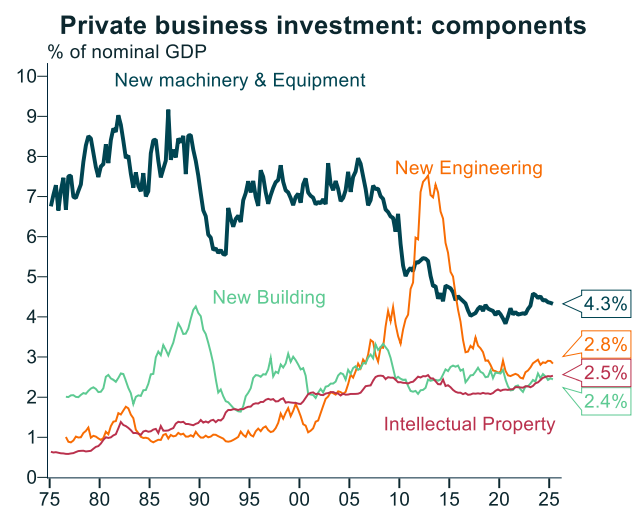

‘Capital shallowing’ has negatively impacted Australia’s productivity by reducing the quantity of capital investment per person.

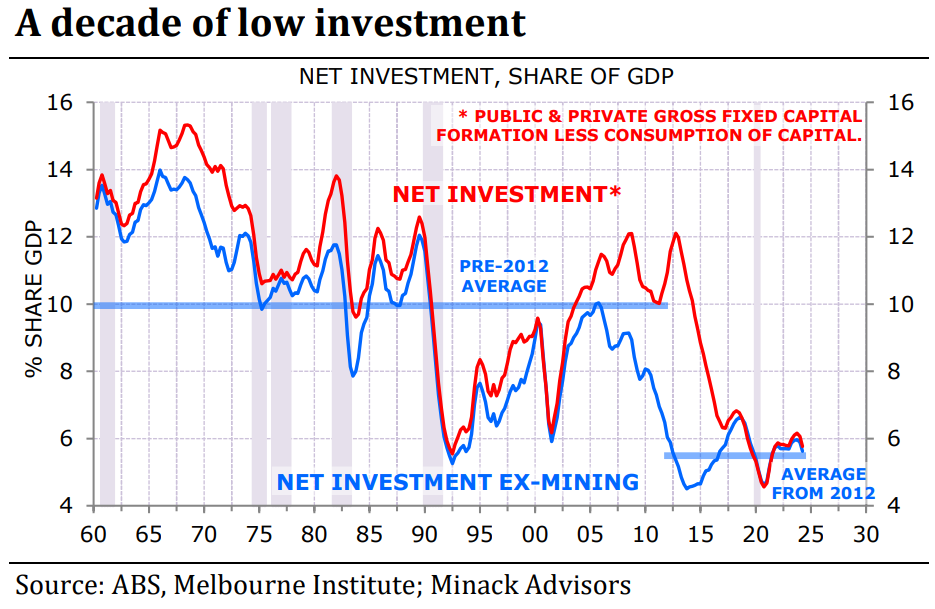

Australians have been caught between recessionary levels of investment as the population has expanded rapidly through immigration.

Advertisement

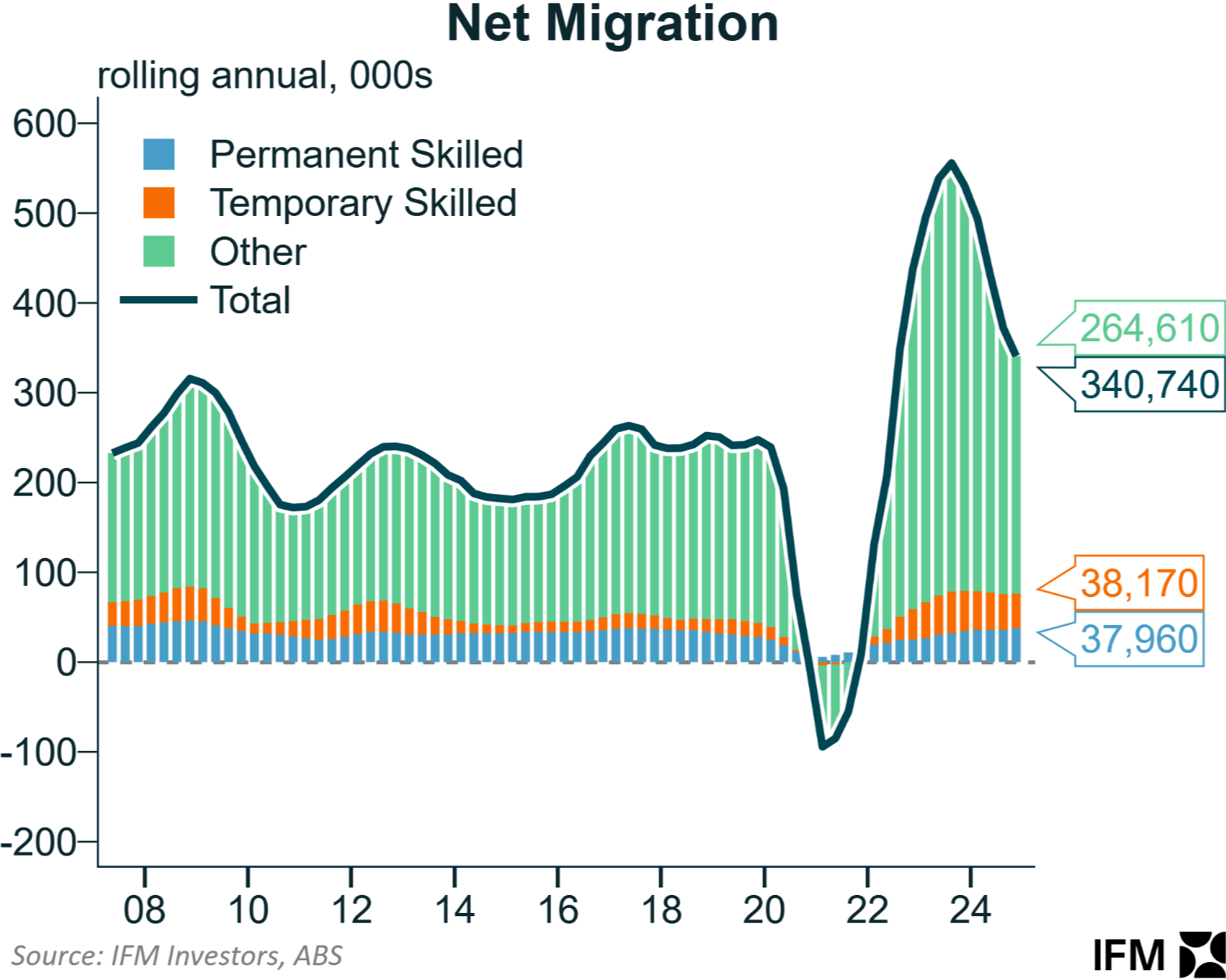

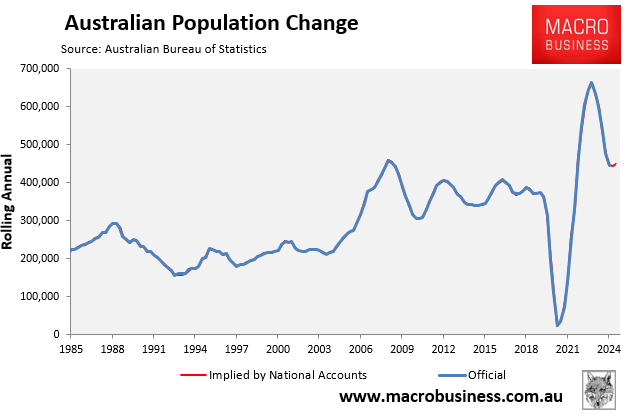

In this context, the Q2 national accounts released on Wednesday were troubling. They suggested that Australia’s population growth has reaccelerated.

At the same time, non-mining business investment is severely depressed. The amount of investment declined by 0.1% in Q2 to be only 0.1% higher for the year.

Advertisement

As illustrated below by Alex Joiner from IFM Investors, private business investment as a proportion of GDP remains near recessionary levels.

New machinery and equipment—vital to making workers more productive—is tracking at historical lows as a share of GDP. At 4.3% of GDP, it is tracking at around half what it was two decades ago, before immigration was ramped higher:

Advertisement

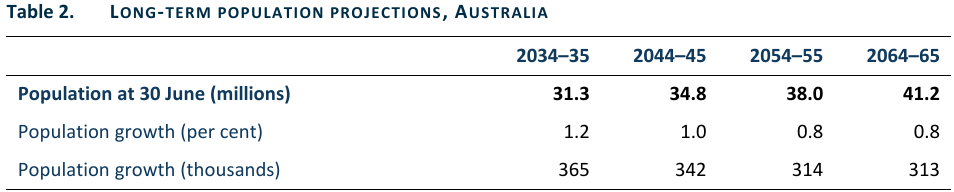

It is hard to see how Australia can realistically lift its capital-to-labour ratio, i.e., experience ‘capital deepening’, and lift productivity growth when it has committed to increasing the nation’s population by 13.5 million over the next 40 years.

Source: The Centre for Population (December 2024)

Advertisement

Adding the equivalent of another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to Australia’s current population in just 40 years will require an unprecedented amount of investment in business, infrastructure, and housing to simply maintain the capital stock per person.

Achieving such levels of investment will be an impossible task, inevitably resulting in the Australian economy suffering further ‘capital shallowing’ and slower productivity growth.

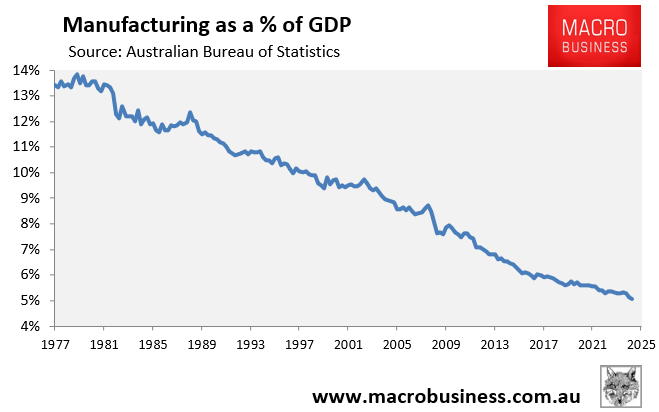

Australia has also committed to energy policy suicide by doggedly pursuing ‘net zero’, which will raise costs throughout the supply chain, force further deindustrialisation, and harm the nation’s productivity and economic potential.

Advertisement

The massive costs of transmission and storage, combined with the intermittent nature of weather-dependent renewables, will ensure that Australia’s energy costs continue to climb, resulting in higher bills, inflation, and additional manufacturing losses.

Australia’s reluctance to reserve adequate gas for domestic use exacerbates the problem, as natural gas is essential for industrial operations and electricity generation (firming). Higher gas costs will also lead to more manufacturing closures and higher wholesale electricity prices.

Advertisement

As a result, Australia’s productivity growth will continue to stagnate, resulting in a less diverse economy and declining living standards.