“I’m not the best photographer in the world, I’m the hardest-working,” Sebastião Salgado told me in a soft voice. His almost perfect Spanish was enhanced by the calm, melodious cadence of his Portuguese: “A photographer belongs to a breed apart: I’m not an artist; a journalist reconstructs reality, but a photographer doesn’t. I have the privilege of looking, nothing more.”

On February 5, 2025, we met at the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, where he presented Amazônia, the last large-format exhibition he opened during his lifetime.

I worked on this profile without suspecting that I would have to adjust the verb tenses for the saddest of reasons: the photographer died on May 23, 2025.

A worker at the Burgan oil field in Kuwait in 1991.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

A worker at the Burgan oil field in Kuwait in 1991.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

A man of extremes, Salgado ignored routine phrases and knew nothing of indifference. One of his recurring words was “colossal.” He liked to cite astonishing statistics with the authority of someone who, in a single day, saw 10,000 people die in Rwanda. He was captivated by the extremes of the human condition: hell and paradise, fall and redemption.

Salgado was born in the small town of Aimorés, Minas Gerais, in 1944. Trained as an economist, he left dictatorship-era Brazil in 1968 and worked in London and Paris. In 1973, he left his position at the International Coffee Organization to devote himself to photography. It was a late awakening. He was about to turn 30 when his wife, Lélia Wanick, lent him a camera. These were the days of analog photography. The main revelation came not in the darkroom, but in the mind: images expressed reality better than numbers.

As soon as we greeted each other, Salgado spoke of the surrounding scenery in his usual superlative style: “It’s the best museum in the world!” He then mentioned a new aspect of the exhibition: the photographs for the blind, which are interpreted by touch. I tried deciphering silhouettes with my fingers, but to no avail. “You just need to be blind,” he commented ironically.

The paw of an iguana in the Galapagos Islands, one of the images Salgado took during a series of 32 trips around the world between 2004 and 2012 in search of primeval nature, which he captured in the work ‘Genesis.’Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

The paw of an iguana in the Galapagos Islands, one of the images Salgado took during a series of 32 trips around the world between 2004 and 2012 in search of primeval nature, which he captured in the work ‘Genesis.’Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Although we were a long way from the jungle, the creator of Amazônia was wearing his usual work clothes: baggy, waterproof trousers with large pockets on the sides, rubber-soled shoes, and a hiking vest. About to turn 81, he walked around the exhibition with energetic ease. He looked in good shape and spoke enthusiastically about future projects. But there’s no way to anticipate the roulette wheel of fate. Some time ago, he had contracted malaria. The after-effects of his travels were in his blood; the threat seemed under control, but it eventually led to leukemia.

From the age of 29 until he was 81, Salgado walked enough to circumnavigate the globe several times over. He lived to chase frames. The documentary The Salt of the Earth (2014), directed by Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, Sebastião’s son, captured his passion for moving, crawling, and creeping in pursuit of a shot. In one scene, he rolls on a pebble beach so that the walruses he intends to photograph won’t notice his presence.

Landscape in Moramba Bay, Madagascar (2010), from the ‘Genesis’ project.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Landscape in Moramba Bay, Madagascar (2010), from the ‘Genesis’ project.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Salgado’s blue eyes conveyed the unusual calm of a restful traveler. His closest friends knew he disliked criticism, especially from colleagues, but in public he reacted with the poise of a Zen monk, worthy of his polished skull, simply saying, “My angel and your angel don’t meet.”

Salgado settled in Paris, where he could disconnect from the turbulence he captured in his photographs. Few settings have the visual appeal of the “City of Light”; however, his Parisian territory consisted of two spaces: his laboratory and his home. “I don’t know of any photos of Sebastião in Paris,” says his close friend Graciela Iturbide. “He likes living there, but his mind is elsewhere.”

A tea plantation in Rwanda (1991), from the ‘Workers’ project.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

A tea plantation in Rwanda (1991), from the ‘Workers’ project.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

During the interview, Salgado seemed to be on no schedule at all. He had woken up at 5:00 a.m., but he didn’t just answer the question at hand; he anticipated the next five with the eloquence of someone who has woven a discourse for years. At the end of the interview, he would comment: “I was exhausted, but I rested by talking.”

I thought it was appropriate to start by talking about the walks with his father: his school of vision. “My photographs are usually set in nature. The sky is a very important part of my photography because I was born on a ranch where the light is the most fantastic thing you can imagine. In October, when the clouds began to form, I would go with my dad to the countryside. He didn’t like riding horses; he preferred to walk for three or four hours; we would climb to the highest point on the ranch and watch the clouds and the sun passing through them. That remains with me.”

Image taken in Guatemala in 1978 for the ‘Other Americas’ project.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Image taken in Guatemala in 1978 for the ‘Other Americas’ project.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Nature can be idealized to the point of distortion. When Mario Vargas Llosa was researching the Amazon to write The Green House, he discovered how easy it was to fall into exaggeration when faced with an immense landscape: “Butterflies bigger than eagles, trees that were cannibals, aquatic snakes longer than a railroad,” he recounted in The Secret Story of a Novel.

Werner Herzog sought a more dramatic approach. In his film Fitzcarraldo, he told the story of a man determined to move a boat through the Peruvian Amazon. Defeated by the elements, the filmmaker published a filming diary with the iconic title: Conquest of the Useless. It’s not easy to dominate an environment that has resisted predators and distorting interpretations for millennia.

One of the images Salgado used in the mid-1980s to portray the work of the miners at Serra Pelada in the Brazilian Amazon, the project that brought him international acclaim.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

One of the images Salgado used in the mid-1980s to portray the work of the miners at Serra Pelada in the Brazilian Amazon, the project that brought him international acclaim.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

In his series on social themes (Workers, Other Americas, Sahel, and even Genesis, dedicated to nature), Salgado powerfully expressed reality; his photographs of the Amazon explored something intimate: the secret life of plants.

Certain artists adopt a “late style” late in life. This is the case with the Beethoven of string quartets, the Goya of the Black Paintings, or the Thomas Mann of Doktor Faustus. Salgado belonged to that lineage. His transition to a different way of seeing depended on the shift from the social to the ecological, but also on a technical transformation, from analog to digital. “All my life I’ve worked with Tri-X,” he said, referring to the world’s best-selling black-and-white film: “I knew it like the lines on my hand. It’s the same with digital: I know my lights.”

One of the snapshots Salgado used to document the Landless Workers’ Movement in Brazil; in this one, peasants celebrate an official expropriation after months of occupation in the state of Sergipe in 1996.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)The pitfalls of fame

One of the snapshots Salgado used to document the Landless Workers’ Movement in Brazil; in this one, peasants celebrate an official expropriation after months of occupation in the state of Sergipe in 1996.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)The pitfalls of fame

Salgado was arguably the most famous photographer on the planet, yet he received mixed reviews. For half a century, he documented injustice and gave away much of his work; however, for some, he was a superstar who promoted an “esthetic of misery,” monopolized museums, and published oversized books.

The plain, affable tone in which he addressed the Mexican technicians working on his exhibition, which earned him the trust of thousands of people, could not have been more modest, but the most harsh comments were directed not at him as a person, but at his way of seeing things. Ingrid Sischy accused him in The New Yorker of the “beautification of tragedy,” and Jean-François Chevrier in Le Monde of practicing “sentimental voyeurism.” There was no shortage of responses in defense of the Brazilian. In his usual aphoristic style, Eduardo Galeano wrote: “Charity, vertical, humiliates. Solidarity, horizontal, helps. Salgado photographs from within, in solidarity.” Without the element of beauty, numerous images would be forgotten. Esthetics generates empathy. Gilberto Owen expressed this enigma in an aphorism: “The heart. I used it with my eyes.”

According to Salgado, those who criticize “photography of misery” do not approach the privileged witnesses in the same way: “Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Annie Leibovitz, the great American photographers who portrayed the rich in their country and who have worked on the great fashion shows, do not receive criticism because it is assumed that beauty belongs to the rich; but if you portray the beauty of the poor, there is criticism because it is assumed that someone poor has to be ugly and must live in an ugly place, but no: they live on our planet, which has a wonderful sky and incredible mountains; I must show that in the midst of their material poverty.”

‘Thanksgiving prayer to the Mixe god Kioga in gratitude for a good harvest,’ in Oaxaca, Mexico, 1980.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

‘Thanksgiving prayer to the Mixe god Kioga in gratitude for a good harvest,’ in Oaxaca, Mexico, 1980.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

“Salgado’s problem is success,” comments Argentine photographer Dani Yako: “His appropriation of themes isn’t just his; all photographers take over the lives of others. At first, he didn’t think about being exhibited; he worked for newspapers, but galleries framed his work differently, and sometimes that leads to misunderstandings. What’s important is his work.”

Controversy rarely leaves a public figure unaffected. On January 17, 2025, The Guardian published an article about Salgado’s ecological photography, Trouble in Paradise for Sebastião Salgado’s Amazônia. The article reported that anthropologist João Paulo Barreto, a member of the Tukana Indigenous community, visited the Amazônia exhibition in Barcelona and left after 15 minutes, shocked by the display of nudity: “Would Europeans dare to exhibit the bodies of their mothers and daughters like that?” he asked. According to Barreto, Salgado viewed Indigenous people with a colonial attitude.

Shortly after, the article was refuted in a letter to The Guardian by Beto Vargas, an Indigenous leader of the Marubo group. Vargas emphasized the importance of portraying the inhabitants of the deepest reaches of the Amazon; the fact that they appear nude is not an artifice; this is how they live and should not be Westernized to be respected. Vargas witnessed the sessions in which Indigenous people themselves discussed how to be portrayed and commented that, thanks to Salgado, Brazil’s Supreme Court enacted the ADPF-70 law to guarantee the medical care denied to Indigenous people during the pandemic by the Bolsonaro government.

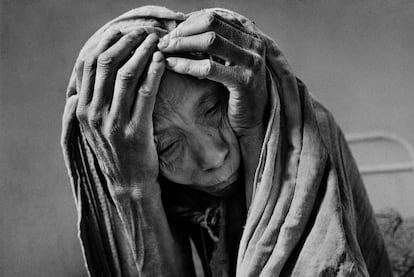

A malnourished and dehydrated woman waits for treatment at the hospital in Gourma Rharous, Mali, 1985. The image was featured in the book ‘Sahel: The End of the Road.’Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

A malnourished and dehydrated woman waits for treatment at the hospital in Gourma Rharous, Mali, 1985. The image was featured in the book ‘Sahel: The End of the Road.’Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

The Guardian report arose from a coincidence: Salgado’s exhibition was presented in Barcelona at the same time as another exhibition in which Barreto himself participated: Amazonias. El futuro ancestral (Amazonia. The Ancestral Future).

Humans love dichotomies: red wine or white wine, the beach or the mountains, Barça or Real Madrid. The Guardian created a needless rivalry between two exceptional projects.

I had the opportunity to interview the curator of The Ancestral Future, Claudi Carreras, a great connoisseur of Latin American culture. “I’m screwed,” he said upon welcoming me at the Center for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona. For eight months, he traveled 6,900 kilometers (4,290 miles) by river to record a natural world that includes not only jungles but also deserts and glaciers, where nearly 300 languages coexist and where pop culture combines vernacular instruments with electric guitars.

He, too, fell victim to the tension that arises between those who defend their roots and those who come from far away. At first, Barreto refused to meet him: “I don’t talk to white people,” he told him in Manaus. However, after meeting with his elders, the Tukano anthropologist reconsidered. Carrera offered him the position of one of the 11 curators of The Ancestral Future, and Barreto contributed the most ethnographic and traditionalist section of the exhibition.

Children fleeing the war in South Sudan, on their way to refugee camps in northern Kenya (2003). Photograph from the ‘Exodus’ project.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Children fleeing the war in South Sudan, on their way to refugee camps in northern Kenya (2003). Photograph from the ‘Exodus’ project.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

For his part, Salgado recorded the peaceful sprouting of plants as only a war correspondent could. Some revelations arrive through contrast.

The truth is, there’s no one way to approach the world’s great nursery. Amazônia and The Ancestral Future were complementary efforts.

The trial of colleagues

I spoke with several photographers about Salgado and decided to keep their statements in the present tense to be faithful to how they viewed a living colleague.

Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, founder of the magazine Luna Córnea, was dazzled by the Other Americas project. This poetic vision of a devastated reality seemed alien to him, free of any attempt to beautify the horror: “The problem lies with advanced capitalism, which causes conflicts and then commercializes them; this controversy not only affects him, but anyone who touches on these issues. His style is unique; Kodak asked you to turn your back to the sun; he seeks the light; he is so virtuous that it is overwhelming.”

Fishermen in the Vigo estuary in 1988.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Fishermen in the Vigo estuary in 1988.Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

If those photos didn’t seduce us, they wouldn’t affect us either. In this sense, beauty provides a moral argument.

Ortiz Monasterio advised Salgado on his trip to Munerachi, in Mexico’s Sierra Tarahumara: “He shot 20 or 25 rolls of film a day, sending them via Federal Express in special envelopes to protect them from X-rays. It’s mind-blowing to see him working under such great pressure; he traveled with a stack of 200 contacts that he reviewed at night. When he was at the Magnum agency, he earned more than all the other photographers; that provokes admiration, but also jealousy and envy.”

For his part, Dani Yako told me over a video call: “Everything about Salgado is grandiose, from the skies to the mass movements. Even in his supposedly intimate photographs, he’s as exuberant as [Gabriel] García Márquez. He achieves something almost unreal; you think it can’t exist: that’s the merit of his quest.”

A simple man can have uncomplicated demands: “When he invited me to his house for dinner, he cooked,” Yako says. “He doesn’t behave like a star. He still lives in the same place as always, but there’s obviously a distance; his life is different: while we were eating, his lab technician brought him photos he had to send to The New York Times aboard the Concorde.”

Salgado’s best friend in Mexico is Graciela Iturbide. I visited her at her home in the Niño Jesús neighborhood of Mexico City. A young man stopped me on the road and asked where I was going. I mentioned the photographer’s name, and he offered me a ride, proud to be the neighbor of a national figure.

Vietnamese refugee camp in Hong Kong (1995).Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Vietnamese refugee camp in Hong Kong (1995).Sebastião Salgado (Contacto)

Iturbide was recovering from a fracture, but she maintained the serene composure which she seems to draw images to her without seeking them out. She had only been out on the street once, to attend the inauguration of Amazônia. She met Salgado in 1980, when he sported a long blond beard and hippie mane: “I have a photo of him from that time: gorgeous,” Iturbide recalls. “His mind and heart were more pristine then, open to surprises. I got him a flash so he could photograph the Basilica of Guadalupe. After that trip, he stayed at my house several times and I let him use my bedroom. Mexico was his gateway to the Other Americas.”

Iturbide and Salgado photographed together in Villa de Guadalupe, Xochimilco, and Veracruz. For every photo of hers, he took a hundred: “He has amazing discipline; he never stops. I’m more of a choosy type. I don’t like rushing; I prefer photos that lead to a development in the lab.”

Iturbide also saw a very different photographer in action, Henri Cartier-Bresson: “Henri waited until he found the opportunity; I wait for the moment too. On the other hand, Sebastião doesn’t stop, which is why it was good for him to switch from analog to digital; he likes to do things quickly, but he develops photos as if they were analog, don’t ask me how. I exchanged 10 of my photos with others of his, but his are large format and I have nowhere to put them. The ones I like the most are those of Serra Pelada. I love being his friend after so many years; there are photographers who stop talking to each other; I can give you examples, but not for the interview.”

The synchronicity between the photographers reached a moment of light and shadow on May 23: Iturbide was honored with the Princess of Asturias Award, the same day Salgado died.

Nature as therapy

Robert Capa died after stepping on a mine in Vietnam, fulfilling one of his axioms: “If the photo doesn’t work, it’s because you weren’t close enough.” His colleague from Minas Gerais adopted the phrase and covered the horror with unprecedented proximity. Far from sensationalism, Salgado sought the dignity of those suffering and used esthetics as a means of protest.

However, recording disasters took a heavy toll. Toward the end of the 1990s, after witnessing burning oil wells in the Kuwaiti desert and following displaced people in Africa, he fell ill with an unprecedented illness, brought on by what he had seen.

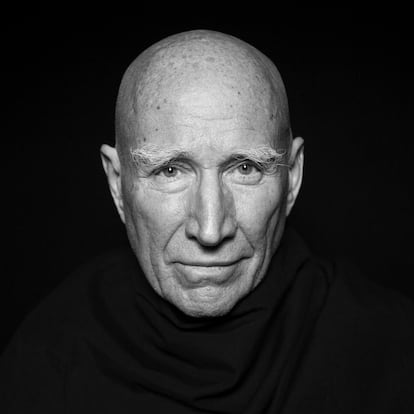

Sebastião Salgado, portrayed in Madrid for ‘EL PAÍS’ in March 2019.Gorka Lejarceg

Sebastião Salgado, portrayed in Madrid for ‘EL PAÍS’ in March 2019.Gorka Lejarceg

It was just then that his father left him the family farm. “I was born in Minas Gerais; our baroque was born there, and my photography is very baroque. I started photography very late, but the impulse came from afar, as did my ideological heritage, which came from a poor, underdeveloped country. I have done social photography almost all my life and began doing environmental photography in 2004, when I understood that I had to return to the planet. I understood the evolution of society when Gorbachev appeared and transformed the Soviet Union; he was just one man, but behind him were thousands of people who needed that; if it hadn’t been him, it would have been someone else.

“Evolution has a collective logic. I worked in Mexico in the 1980s when no one thought about the environment or the protection of nature. When I first came to Mexico City, I found a mineral city; today it’s a green city; if you look closely, all the trees are young, 20 or 25 years old. My photography follows the changes of the human species. I worked a lot in Africa, I was involved in the genocide in Rwanda, and I covered the reorganization of the human family in the series Exodus. What I saw in Rwanda was the most terrible thing I’ve ever seen; I became psychologically and physically ill. I went to see a doctor because I felt so bad, and he told me: ‘Sebastião, you’re not sick, you’re dying. If you continue like this, you won’t be able to go on, because your body has entered a state of destruction.’”

Brazilian essayist Ricardo Viel, who works for the José Saramago Foundation in Lisbon, attended a lecture by Salgado about 15 years ago: “He had trouble remembering things,” he told me at the Casa dos Picos, which houses the Portuguese novelist’s legacy. “When I talked to him, he seemed to have lost his memory and frequently went to Lélia to ask her for clarifications.”

In our conversation, Salgado returned to that critical moment: “I went to Brazil, we rented a little house on the beach, and I decided to abandon photography; I was ashamed of being part of such a predatory, brutal species.”

The family farm, which had been a productive orchard, was completely eroded. Salgado decided to restore it. For every photo he had taken, he planted a tree. By 2014, the land that had been barren in 2001 had flourished in an extraordinary way.

As the countryside turned green, he healed: “I saw the trees emerge and the insects return, and with the insects, the birds, and then the mammals. I was healed, regained great hope, and decided to return to photography.”

No colleague had ever taken so many helicopters, canoes, horses, mules, or small planes. “How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man?” Bob Dylan wondered. In the case of Salgado, who traveled to more than 100 countries, one might ask if there was any road he missed.

When he returned to his craft, he did so in an epic way. Between 2004 and 2012, he embarked on 32 trips. The result was Genesis. “I wanted to see my planet, what was pristine about it, what hadn’t been destroyed. I went to Washington, to Conservation International, and discovered that 47% of the planet was as it was at the moment of genesis — not the habitable parts, but the highest, wettest, coldest, most desert-like lands — and off I went. For eight years, I gave myself the greatest gift a person can give themselves. But the most important journey was an inner one. I understood that I am nature. When I was in northern Alaska, I had a very fat Inuit guide, shorter than me, who couldn’t climb the mountains. We landed on very narrow, short airstrips, and the plane couldn’t carry much weight. I preferred to remain alone, without the Inuit. In the mountains, accompanied by plants and minerals, I understood that I was one among others. There I regained hope, not in my species, which doesn’t deserve to be on this planet, but in a planet that is rebuilding itself.”

For decades, Salgado was a ground-level witness. In the Amazon, he had to take off to capture vast spaces: “There are no special planes to photograph the forest from above, nor are there drones because there are no bases to fly them. The largest mountain range in Brazil is in the Amazon, but there are no photographs of it because there is no access. I had to turn to the army, the only institution with representation in that territory, with 23 barracks. They agreed to let me travel in their planes, with the doors open for photography. These weren’t missions [put on] for me; I joined the ones they had [planned] and contributed fuel (45,000 liters); that’s how I was able to photograph a region of almost 500 kilometers, a group of islands formed during the last period of the Ice Ages.”

This memory ignited his enthusiasm for the unprecedented: “I was able to photograph aerial rivers; it’s a new scientific concept, one that’s been talked about for about eight or 10 years. The evaporation from the rivers and lakes of the Amazon is immense; it’s the only area on the planet with its own evaporation that guarantees rainfall. This forms colossal clouds. The volume of water that emerges into the air is greater than the water that the Amazon River discharges into the Atlantic Ocean.”

The second journey: memory

What did Salgado dream about? “After a heavy dinner, I have nightmares. I go back to the days of analog photography, dreaming that I don’t have film and I’m shooting with nothing in the camera, or that the film was exposed to light and everything was blurred.” At night, all the photos he had taken didn’t calm his subconscious. During the day, he transformed them into memories.

For John Berger, the antecedent of photography is not drawing or engraving, but memory. The image is a temporary certificate.

On the verge of turning 81, Salgado reflected on his age. Unbeknown to him, we were on the threshold, and his words took on dramatic weight with his death: “We live very short lives, 80, 90 years. If we lived thousands of years, we would think differently: we would understand the mountains. But we pass through the world very quickly; it is necessary to make an effort to capture nature. I remember one day I was in the Amazon with Lélia, and a military helicopter flew over; we took off with the doors open in that Black Hawk, and I was busy photographing until I looked away and saw Lélia crying. I asked her what was wrong, and she said, ‘It’s beauty.’ Paradise was all around.”

How to choose the moments of hell or paradise? “Photography is living within a phenomenon that you portray from the beginning, waiting for it to reach its climax. You keep photographing until it loses intensity and disappears. Next Saturday, I’ll be 81, and I can’t start a long project anymore; I’m traveling within my life, returning to my contact sheets. I have more than 600,000 postcard-sized photographs, and I love the second trip of reviewing them. The other day I was editing some photographs I took in the mountains of Ecuador in 1976 or 1977. I got hepatitis there, but I didn’t have the money to return to Paris, and I worked while sick. When I returned to those photographs, I got sick again! I photograph with the same intensity as I edit; I smell the smell of pork rinds in the mountains of Ecuador! In the photos of Mexico, I remember the tequilas I drank.” Salgado looked up, remembering something distant, and John Berger was right again: photography belongs to memory.

With celebratory enthusiasm, Victor Hugo wrote to the photographer Edmond Bacot: “I congratulate the Sun for having a collaborator like you.” He would have congratulated Salgado for his clouds.

During the conversation, I mentioned Mário de Andrade’s novel Macunaíma, which is set in the Amazon and ironically depicts a region “full of vermin and poor health.” To avoid the danger of working, the protagonist repeats an existential motto: “Ah! Just so lazy.”

The most active of photographers admired the story starring a slacker. After our talk, he asked if we could look at a photo of the Macunaíma landscape. “There it is,” he said, pointing at the river with the discretion with which one points at a person so as not to offend them.

The death of Sebastião Salgado, which occurred shortly after our meeting, gave testamentary value to one of his phrases: “We pass through the world very quickly.”

His legacy, made of moments, is already inscribed in memory.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition