A fat guy sits at a table looking glum. Blobby and balding, he wears scruffy sandals and a shapeless jumper. If you saw him in the street you’d have him down as the owner of a hardware store, or perhaps one of the unfortunates done over by the Post Office. Never in a month of Mondays would you suspect him of being a celebrated artist.

But wait, there’s worse to come. On the wall next to John Bratby (for it is he) sits a naked woman with a face so doomed she should be sitting on death row rather than at a kitchen table overflowing with breakfast mess. Poor Mrs Bratby (for it is she) — what a life of humiliation and degradation she must be living. She’s an artist too. Her maiden name was Jean Cooke.

He painted her. She painted him. And their matching explorations of marital misery share an angsty room again in Seeing Each Other: Portraits of Artists at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, where they seem to be in competition to see who could better capture the grimness of their union.

Mrs Bratby by her husband, John . . .

SOUTHAMPTON CITY ART GALLERY/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

. . . and John by Mrs Bratby

ROYAL ACADEMY OF ARTS, LONDON/PHOTOGRAPHER: ANDY JOHNSON

In real life Bratby, the founder of the “kitchen sink” school of painting, was a violent abuser who painted over his wife’s art, slashed her canvases and restricted the hours she was allowed to work. She eventually left him, but they had four children together so there was a lot of suffering to be survived for the sake of the kids. Art has been many things in its past, but not until it reached Britain in the 1950s did it become such a vivid recorder of squalor in a marriage.

The Pallant House show looks back at the way British artists have painted other British artists in a timeline that starts at the beginning of the 20th century and continues until today. I dwell on the Bratby face-off because it’s the most obvious example of something unsettling and even creepy that emerges at this event: when it comes to recording unease, vulnerability, unhappiness, no one does it as sharply as the Brits.

• Turner and Constable were rivals — but did they need each other to thrive?

In a show packed with hundreds of faces, I could find one smile: the shy one sported by Ishbel Myerscough in the cheeky double portrait by her pal Chantal Joffe in which the two of them stand before us in baggy bras and saggy tights, and demand that we compare their middle-aged display of Marks and Sparks underwear with all the other undressed women in art. This too, with its twinkle of saucy seaside humour, is a very British picture.

Artists have, of course, been painting other artists for much longer than this event’s timeline and for many different reasons, most of which could be described as conspicuously un-British. The earliest example I can think of is Raphael’s Vatican masterpiece from 1511, The School of Athens, in which Michelangelo and Leonardo make guest appearances in the guise of heroic Greek philosophers. The younger Raphael is celebrating the genius of his older masters by imagining them at the summit of ancient civilisation. We’re about as far away from the world of John “the kitchen slob” Bratby as it is possible to get in art.

Detail of The School of Athens by Raphael, 1511

ALAMY

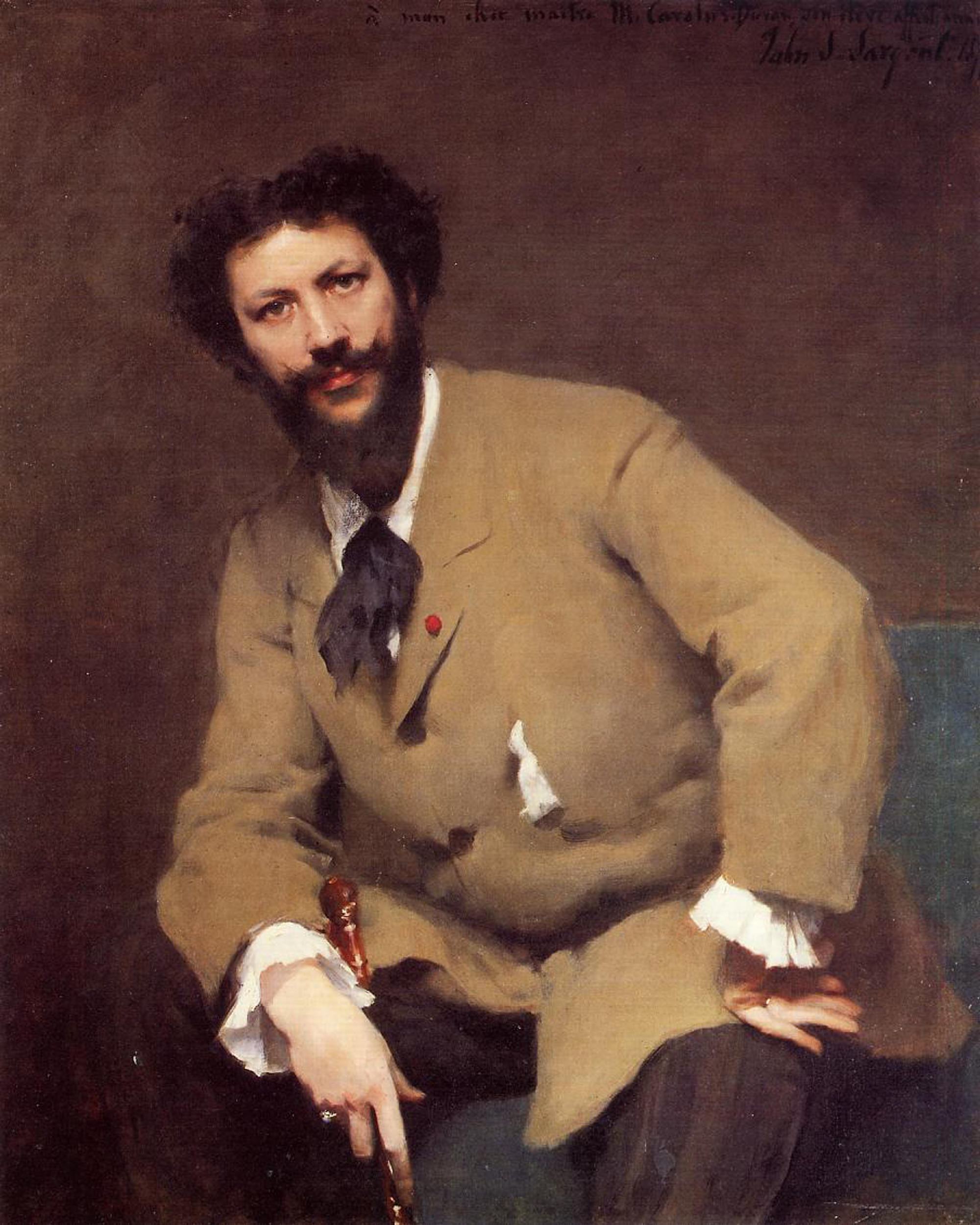

This idea that an artist would paint another artist to celebrate them has a dazzling history. When the great Velázquez painted the brilliant Spanish sculptor Juan Martínez Montañés, in the darkly thoughtful portrayal from 1637 that now hangs in the Prado in Madrid, he was honouring the older artist and making his admiration plain. The same is true of Renoir’s 1875 portrait of Monet, or John Singer Sargent’s posh memory of his fabulously successful teacher, Carolus Duran, from 1879. One artist is generously crediting another artist.

When did that change? If I had to settle on a suspect it would be Gauguin’s 1888 portrait of Van Gogh painting his Sunflowers, on display now in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Everyone thinks of Van Gogh and his Sunflowers as a joyous explosion of horticultural ecstasy and summer love. But not Gauguin. And he should know. He was there in Arles, France, living in the same house when Van Gogh went sunflower crazy and cut off his ear.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s1875 portrait of Claude Monet

ALAMY

John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Carolus Duran, 1879

ALAMY

We’re not at Bratby levels of domestic unhappiness in Gauguin’s portrayal of his unstable and obsessive housemate — there’s a long way to go before we get to that — but there is tangible tension and unease. Art is no longer in the business of honouring its greats. It has crept closer and started to fret about them.

• Read more art reviews, guides and interviews

Which just about gets us to Britain in the 1910s and the start of the Pallant House timeline. Indeed, Roger Fry, the art critic and painter who introduced and championed Gauguin and the post-impressionists in Britain, turns up in this show with a downcast portrayal of his lover, the painter Nina Hamnett. Staring deep into the distance, she looks as if she is remembering the death of her mother rather than posing for her latest romance.

Nina Hamnett by Roger Fry, 1917

UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS ART COLLECTION

As a nation of painters, Britain seems reluctant to the point of incapability to see glamour or joy or intellect or elegance in its own artists. The Bloomsbury bunch played pass the parcel with each other when it came to shagging, but on the evidence of their portrayals of themselves the frantic bed-swapping led only to tension and disruption.

Later in the show Francis Bacon is unhappy. Lucian Freud is unhappy. Leon Kossoff is unhappy. Paula Rego is unhappy. When the snippy Sarah Lucas portrayed the skanky Maggi Hambling, she described her as a lavatory surmounted by two naked lightbulbs.

This is a riveting journey, excellently curated and directed. But its meta message is that Britain is a nation of creative bunnies in pain. My advice to its artists is: open a post office. You’ll be happier.

Seeing Each Other: Portraits of Artists at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, to Nov 2

What exhibitions have you enjoyed recently? Let us know in the comments below