Golf architecture nerds love a design contest. Since 1998, the Alister MacKenzie Society has operated the annual Ray Haddock Lido Prize, which encourages amateurs and up-and-coming professionals to submit sketches of imaginary par 4s. Past winners have included the likes of Thad Layton, Riley Johns, and Clyde Johnson, as well as Fried Egg Golf’s creative director Cameron Hurdus, who took top honors three times. (He is now barred from participating. Too good, I guess.)

It is rare, however, for such “armchair architect” competitions to result in real-world golf holes.

A notable exception was the first Lido contest, which the Ray Haddock Lido Prize commemorates. In June 1914, the golf editors of Country Life magazine, Bernard Darwin and Horace Hutchinson, announced “a novel and interesting competition in golfing architecture”: “Mr. C.B. Macdonald, the designer of the famous National Golf Links of America, has empowered us to offer three prizes… for the best original design for a two-shot hole. Mr. Macdonald is now embarking on the making of a new course at Long Beach, near New York, and hopes that some of the designs submitted may be of assistance to him in that scheme.” This new course turned out to be the Lido Golf Club, which closed permanently during the Great Depression and was recently re-created in Wisconsin by Tom Doak and Brian Schneider.

{{inline-course}}

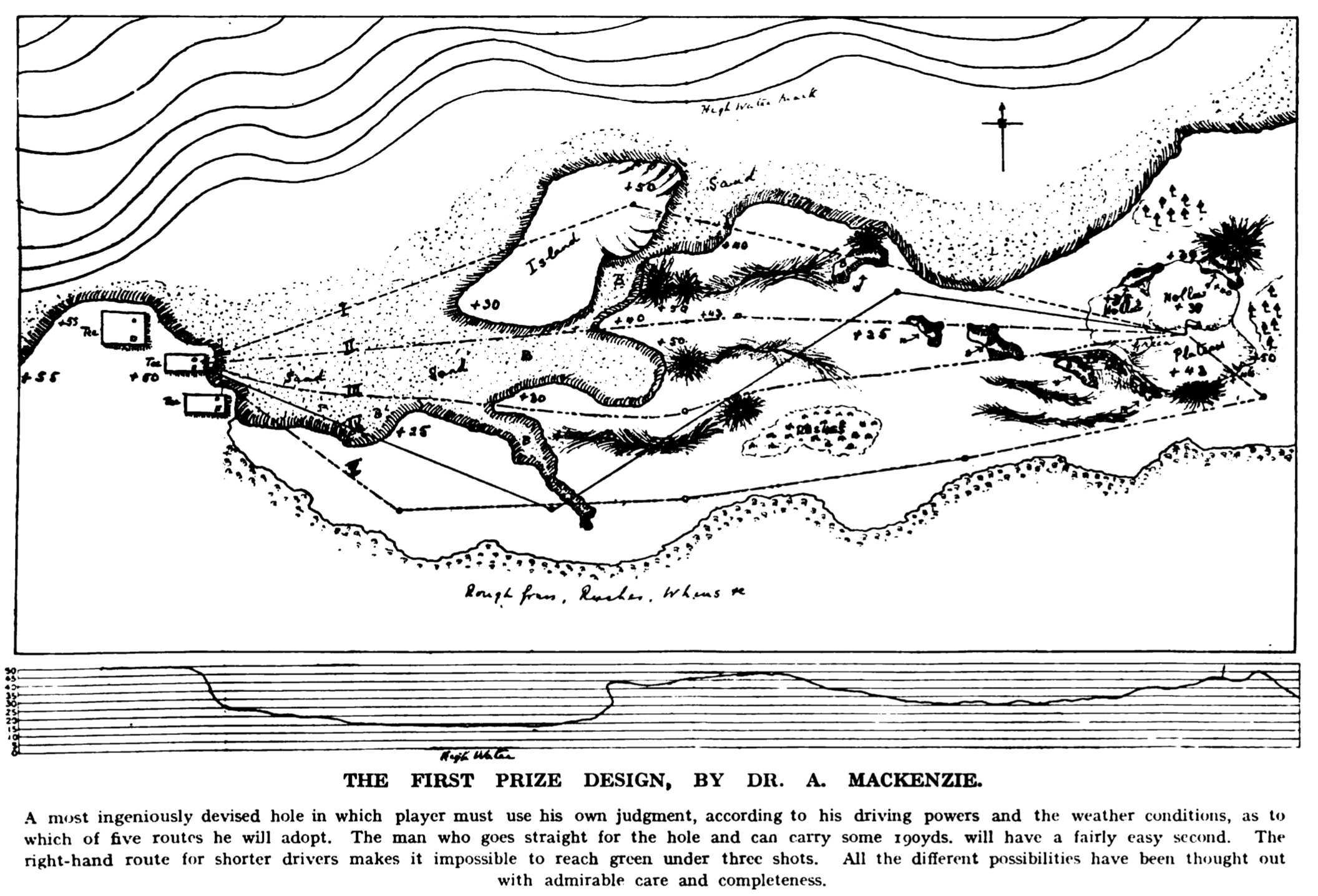

The first-place submission is well known. Created by a 44-year-old physician named Alister MacKenzie, the design is nearly absurd in its intricacy: a long par 4, set on a stretch of coastal cliffs, with five distinct lines of play, a multitiered green, and an alternate fairway occupying an island on the beach.

Alister MacKenzie’s winning design

Alister MacKenzie’s winning design

Macdonald did his best to turn MacKenzie’s hyperactive fantasy into reality on the 18th hole at the Lido. He dispensed with the coastline, obviously, but managed to retain the dimensions and strategic essence of the prize-winning concept. Doak and Schneider’s reproduction of the hole shows how clever Macdonald’s adaptation was: the island fairway may not sit on a literal island, but it serves its function well. The green is a good match, too, with its two back plateaus and lower front section.

The 18th at the Lido (Fried Egg Golf)

The 18th at the Lido (Fried Egg Golf)

The second- and third-place finishers in the 1914 contest were hobbyist-grade efforts from “Mr. A.W. Edmondson” and “Mr. David MacIver.” (“Mr. MacIver will, I trust, pardon me for saying that he has clearly triumphed by pure force of intellect and not by any of the niggling arts of the draughtsman,” Darwin noted politely).

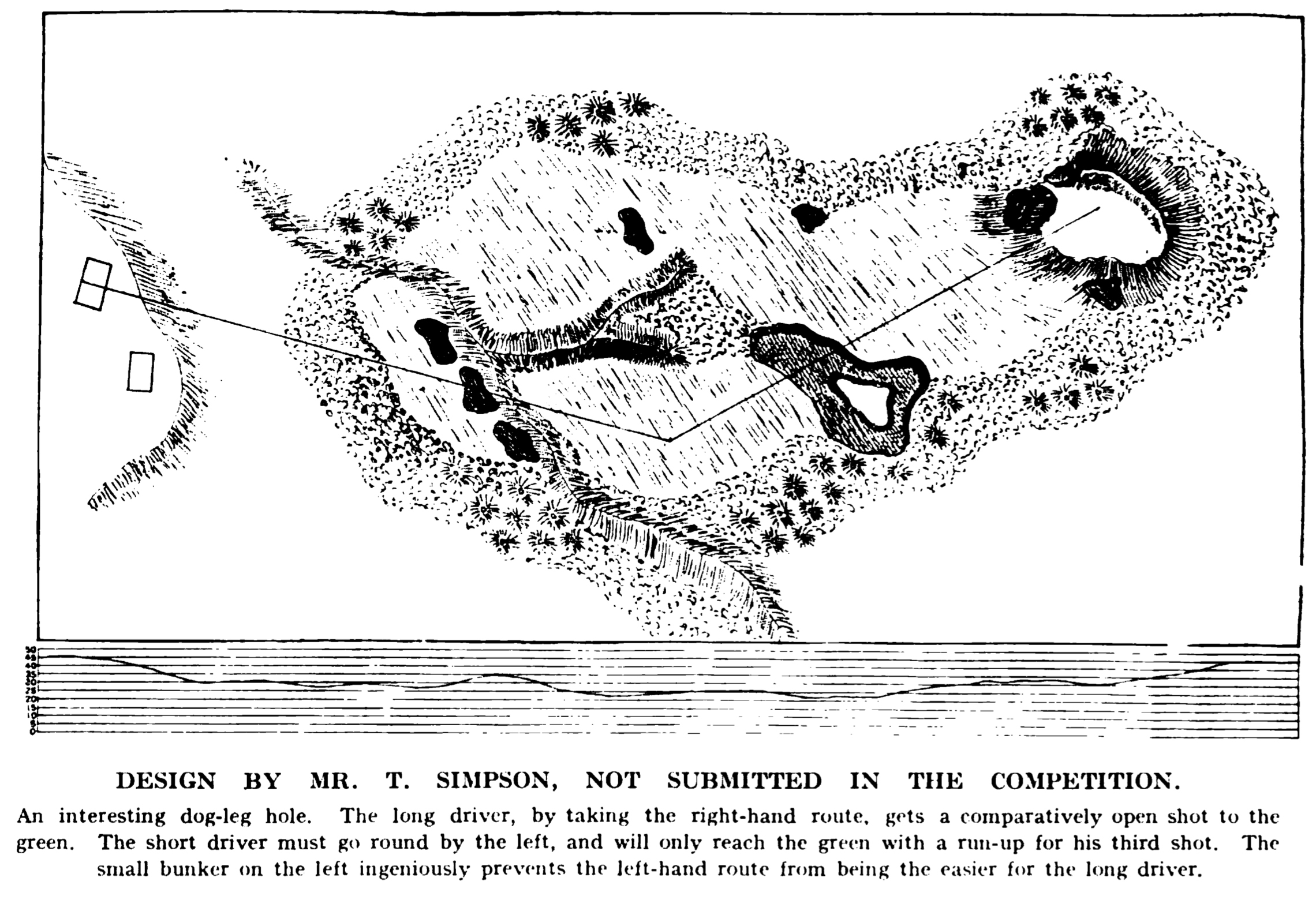

As a non-competition submission, English architect Tom Simpson sent in an excellent par-4 design featuring a diagonal brace of fairway bunkers and multiple distinct landing areas for tee shots. Simpson’s hole was just as strategically sound as MacKenzie’s but far simpler and more replicable.

Tom Simpson’s submission

Tom Simpson’s submission

Macdonald liked the concept enough to incorporate elements of it into the 15th hole at the Lido, aptly named “Strategy.”

The 15th at the Lido (Fried Egg Golf)

The 15th at the Lido (Fried Egg Golf)

At the time, MacKenzie and Simpson were just getting started in golf architecture. MacKenzie had done some work at his home club, Alwoodley, that had impressed Harry Colt, and Simpson had written articles for Golf Illustrated and partnered with Herbert Fowler on a few projects, but both rose to much greater prominence in the 1920s and 30s. No doubt they benefited from the publicity of the Lido competition.

Will the winner of the FEGC Hole Design Contest become the next Alister MacKenzie or Tom Simpson? Well, probably not. But you never know.