I have a fun and cute personal connection with probably the single most climate-destructive individual alive today. Twelve years ago, I made an infographic that attempted to illustrate the absurd variety of symptoms attributed to “wind turbine syndrome”. Donald Trump found it, and posted it as proof of the harm of wind turbines (to aid his fight against a Scottish project near one of his golf courses). When I pointed out he’d missed the point, he instantly blocked me. You hurt me deep, Don.

I’ll forgive him. It was a nice early education in an extremely important principle: the shotgun-blast of hollow and ridiculous rationalisations will constantly change, but the underlying hostility towards clean technologies will not. For the foreseeable future, right-wing forces will deeply loathe wind and solar. The actions of the Trump administration have been swift. Recently, it issued a stop-work order on an 80% completed offshore wind farm (the developers are currently suing to try and reverse it). This is in addition to the broader efforts to kill clean power subsidies for wind and solar in the US.

This stuff usually takes years to show up, but there is already a clear, systemic effect occurring in the US, as recent data from Global Energy Monitor shows. “Total solar capacity currently under construction or in pre-construction is around 92,000 MW, down from around 112,000 MW at the same developmental stages in 2024”, with wind having dropped from 74,000 to 64,000 in the same period. Gas is exploding, having doubled in planned capacity from this time last year.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1217824

One common talking point featuring in the “permitting reform” push (kind of a proto-“abundance”) is that deregulating the energy space will, yes, allow just a teeny bit of new fossil fuels to be built, but it would also unlock massive volumes of new wind and solar, which the free market would flock to on the grounds of their delectable cheapness. It’s clear now that vision of the future grants far too much political invulnerability to the growth of renewables, particularly to solar power. There has also been plenty of well-meaning discussion of “positive” tipping points, such as societal adoption of electric vehicles, but that has been criticised as a problematic oversimplification.

Far from being an unstoppable, self-sustaining runaway technological revolution, swapping dangerous fossil fuels out for safer technologies is something that will always be messy, hard and in need of persistent activist and government involvement to varying degrees. There is clearly enough baked into the global human energy system that the eventual replacement of fossil fuels with cleaner alternatives is inevitable, but it is the rate of change, not the end point, that decides exactly how screwed we are by the combustion of coal, oil and gas.

Independent. Irreverent. In your inbox

Get the headlines they don’t want you to read. Sign up to Crikey’s free newsletters for fearless reporting, sharp analysis, and a touch of chaos

By continuing, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

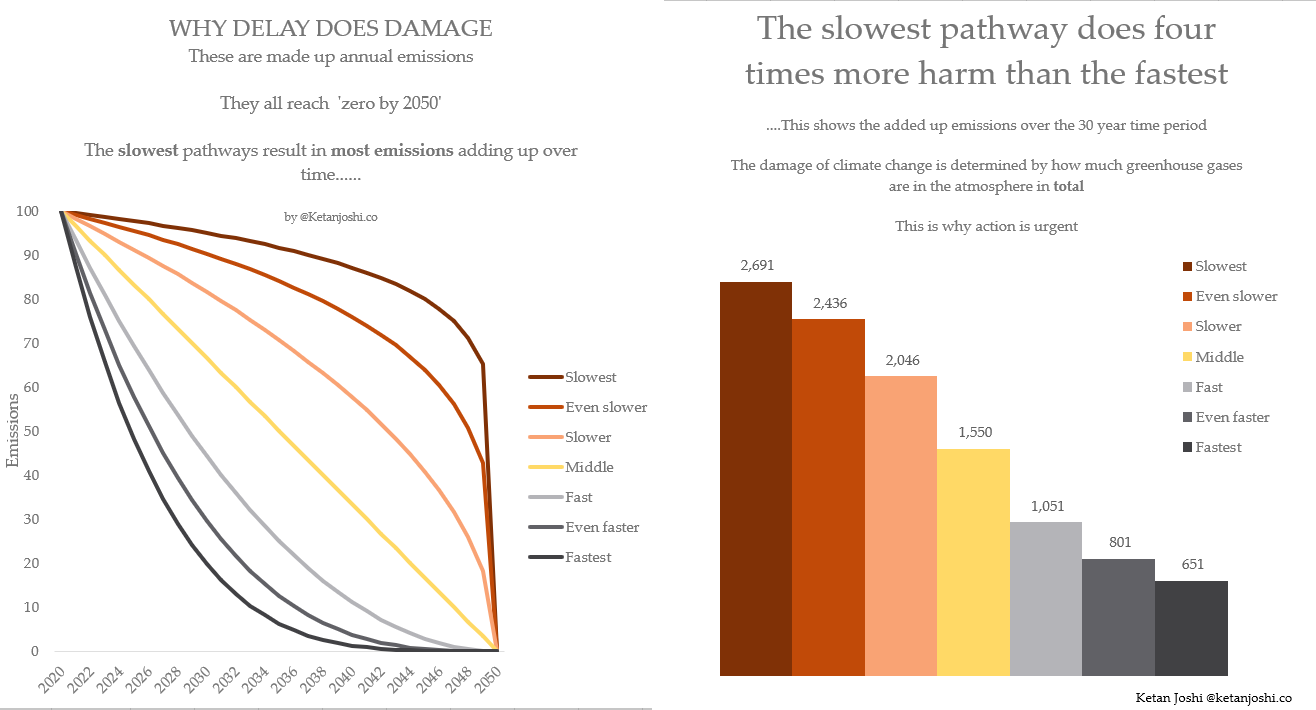

To briefly explain this, imagine the Earth’s atmosphere is a bathtub, and the more filled it becomes with water (greenhouse gases), the more we overheat. When your bathtub is on the verge of overflowing, you turn the tap off fast, whipping it closed, because you understand that your goal is stopping the flow ASAP, rather than just eventually turning the tap off at some point in the future.

I’ve illustrated this below with some made-up numbers. Even if we reach net zero by 2050, we could cause roughly three times the damage if we take the “slow path” rather than the “fast path”. Point-in-time targets tend to obscure the sheer physical damage caused by near-term delay.

You can really see the dynamic of this urgency erasure at play in Australia’s power sector. Recently, the grid regulator (the Australian Energy Market Commission, AEMC) added emissions reductions into the “National Energy Objective” (NEO). This means the regulator actually considers alignment with pre-existing climate targets in its decisions. It should be a great thing. But those targets are almost exclusively “point-in-time” targets, meaning heel-dragging along the way, resulting in more planetary heating damage, is not considered.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1214805

Its addition also meant that in 2024, the grid planner, Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), opted to only include in its biennial system plan (ISP) scenarios that see full achievement of each jurisdiction’s climate targets, along with federal targets. The “slow change” scenario, for instance, was deleted, and any visualisation of emissions was also deleted. Examining the cost and consequences of a delayed transition does occur, but exclusively in the context of price and reliability. As long as we hit future targets, delays on the pathway are seen as a non-issue.

Australia has had undeniable success in the rollout of renewables, and particularly with solar. What is less well-recognised is that the growth of renewable energy and the elimination of coal have both been far slower than projected or modelled by various players in the space, over the past half-decade. That has resulted in a delayed power sector transition: additional emissions along the way, which will cause irreversible harm to life.

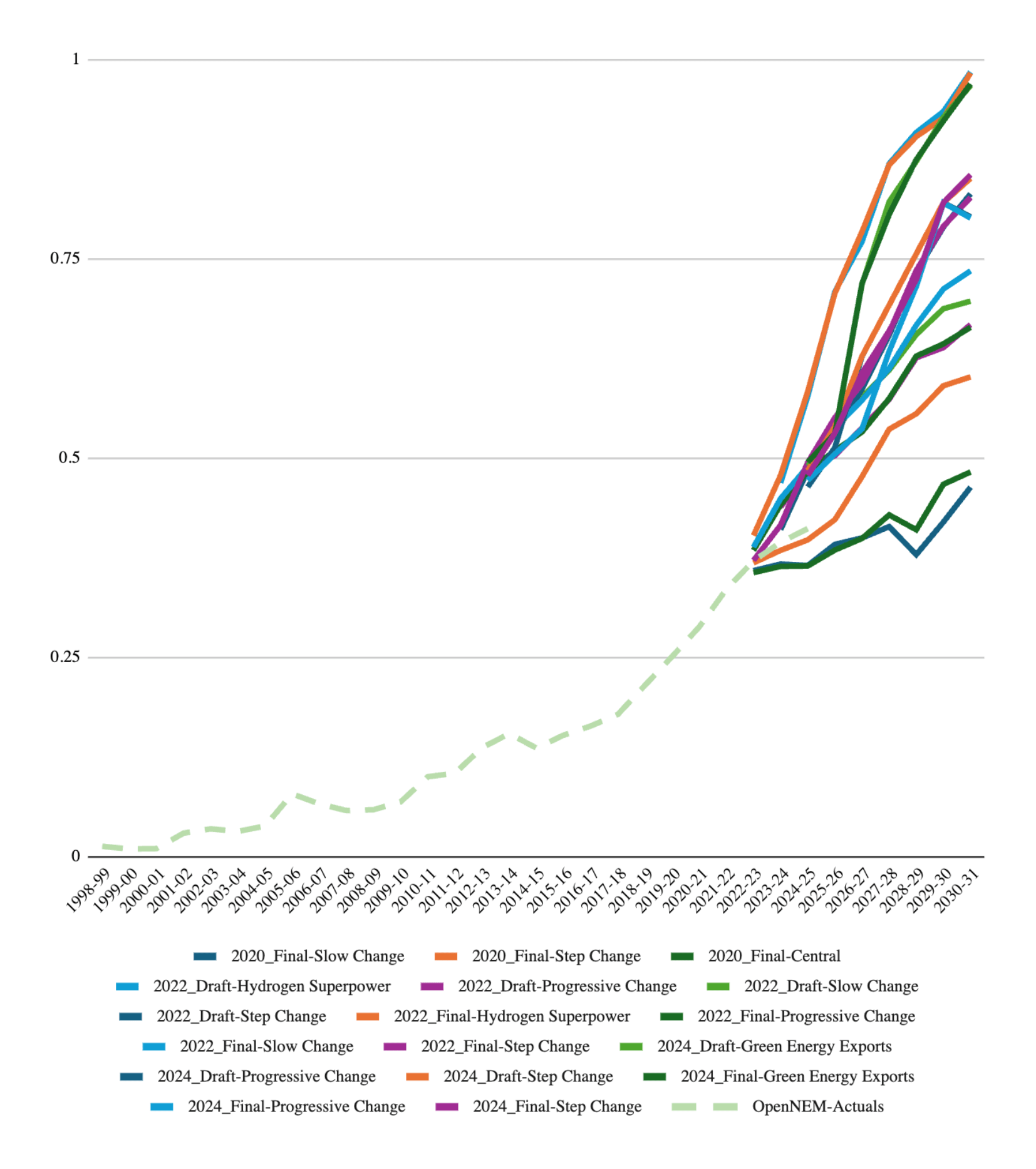

The most recent AEMO ISP assumed a likely share of renewables between 46% to 48%, for the financial year 2024-25 (FY25). The previous two editions, among various scenarios, put the same year’s share between 37% up to around 55%. It ended up at 41%: lower than all of the scenarios put forth in the 2022 and 2024 editions of the ISP. These stumbles are bad enough to suggest a cause beyond seasonal variations in wind, water or solar power.

Source: AEMO ISP editions 2020-2024, OpenNEM

Source: AEMO ISP editions 2020-2024, OpenNEM

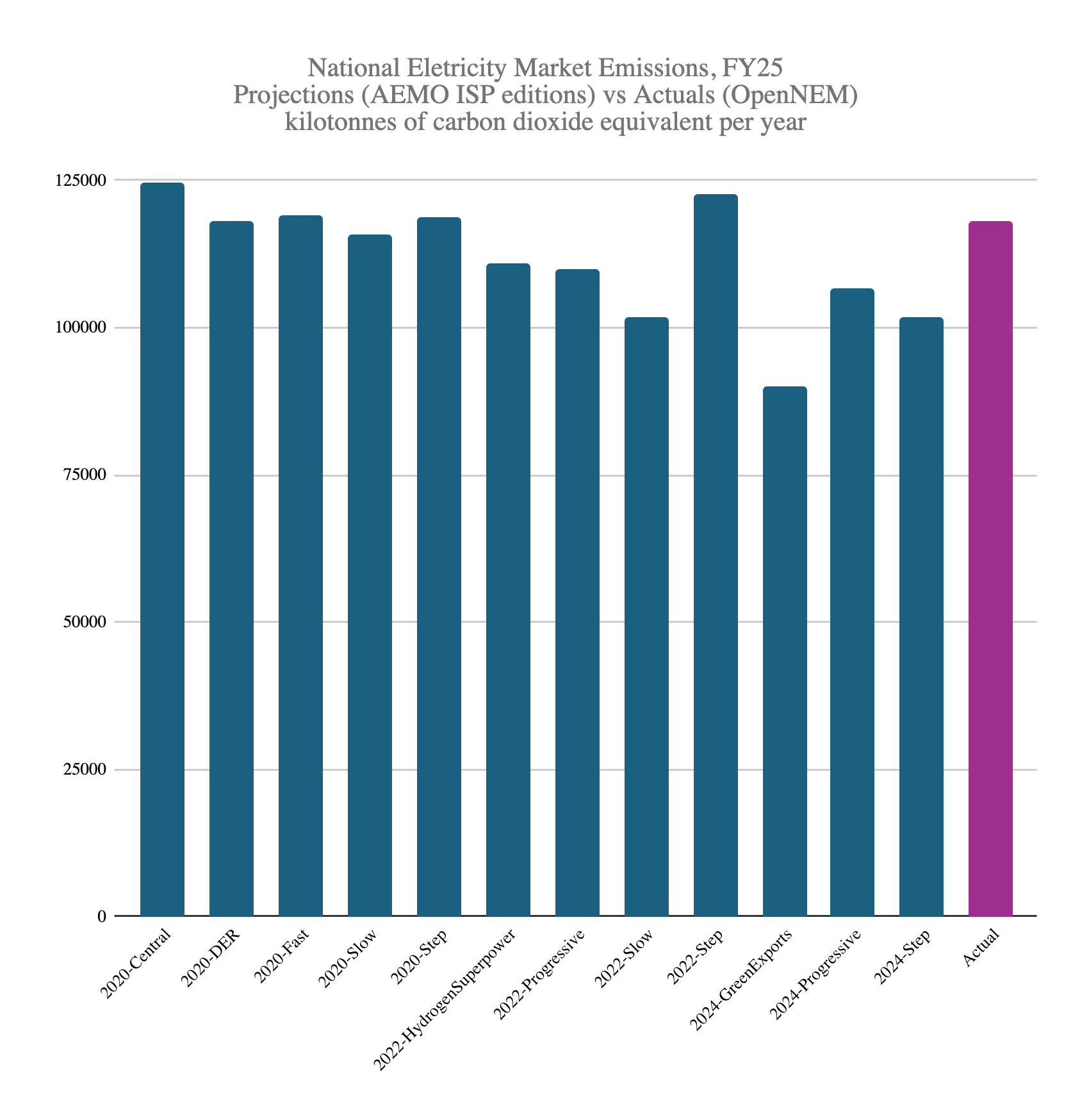

It’s the same story when you look at the absolute emissions of Australia’s power sector too, which seem to be falling way too slow. Rising power demand thanks to hotter fossil-fuel-intensified summers and data centre expansionism means any new renewable energy simply serves new load instead of cutting down into fossil fuel output.

Source: AEMO ISP Editions 2020-2024, OpenNEM

Source: AEMO ISP Editions 2020-2024, OpenNEM

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1208875

The latest quarterly report from the Clean Energy Council found that “just 1,173 MW of new utility scale generation projects have been committed so far in the first half of 2025, which represents roughly one third of the run-rate required (6-7 GW per annum) for Australia to stay on track to reach its 82% renewable energy target by 2030”.

There are also growing noises from energy companies to extend the operational life of the biggest and second-biggest coal plants in Australia: Eraring (after an earlier extension) and Bayswater. When those debates become more prominent, the focus will be on price and reliability, and not at all on the physical harm caused by the additional planet-warming pollution they pump out.

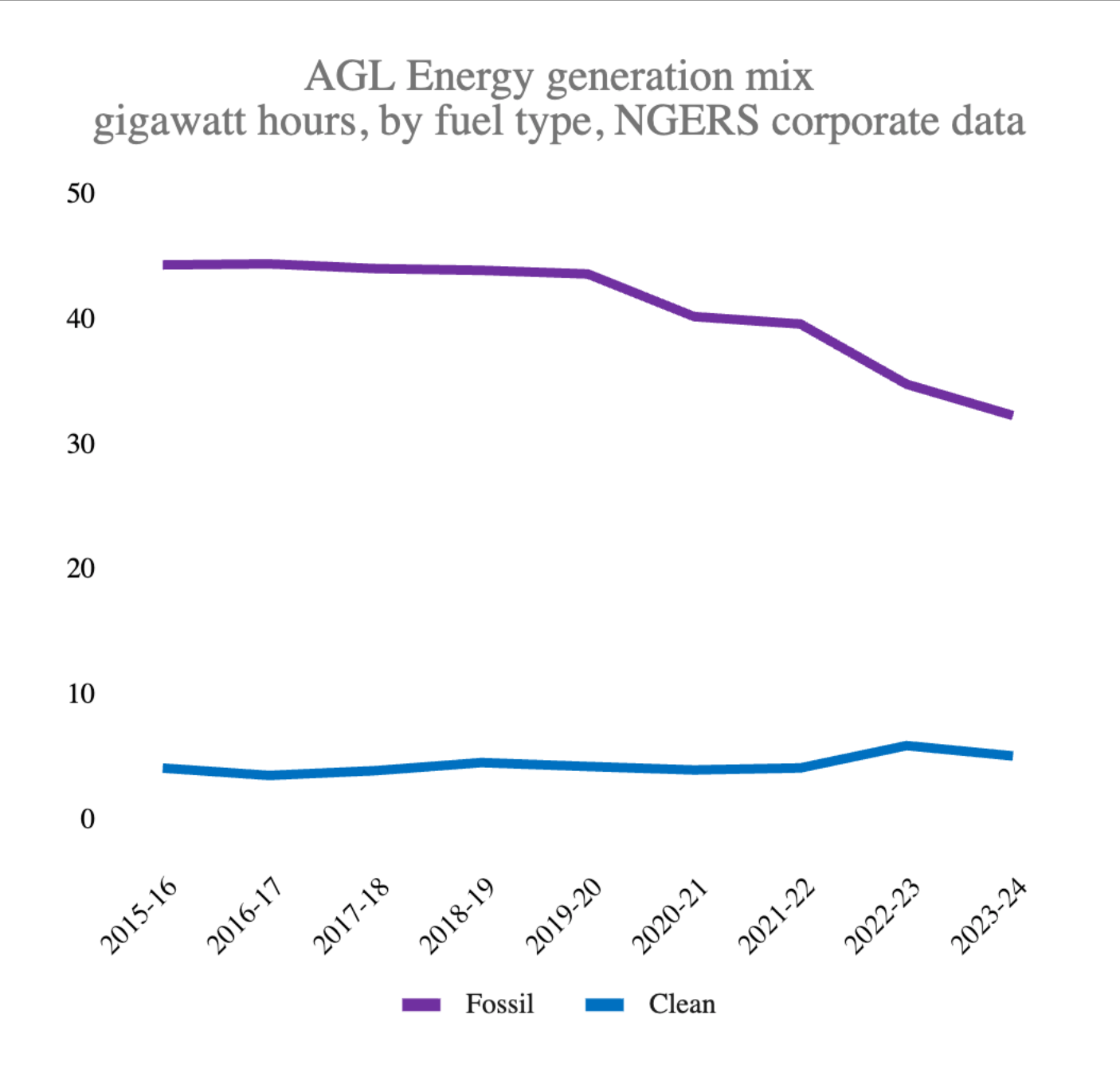

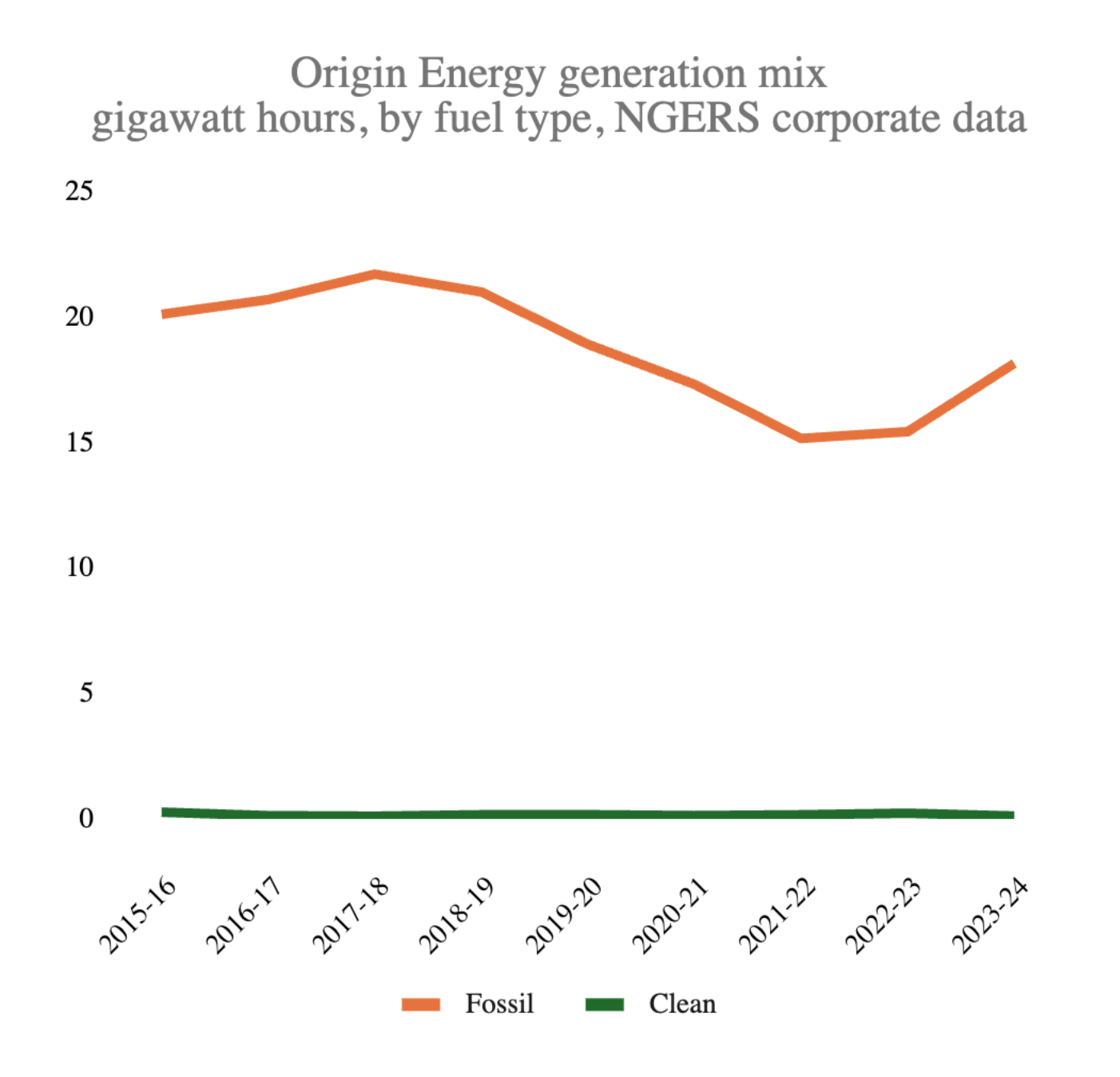

Despite the federal government’s “Capacity Investment Scheme”, there is still nowhere near enough momentum in the growth of new wind and solar in Australia. The two biggest retailers, AGL Energy and Origin, shoulder much of the blame — while their aging coal plants drop offline, they haven’t been building out replacement energy in their portfolio:

Source: National Greenhouse Energy Reporting scheme

Source: National Greenhouse Energy Reporting scheme

Source: National Greenhouse Energy Reporting scheme

Source: National Greenhouse Energy Reporting scheme

There is definitely no magic cure for shifting Australia’s power grid back to a reasonable trajectory. The messy “mid-transition” challenge is emerging in power sectors around the world. But whatever mix of active, aggressive and urgent actions need to be taken, they simply won’t exist without the acknowledgement that hot-swapping the country’s single largest interconnected machine in an overheating atmosphere (and overheating geopolitics) requires sustained, unending effort, alongside broader recognition that short-term delay does real damage.

Fossil-owning power companies will shake their heads sadly at the lack of progress, shrug and say something along the lines of “we’ve tried nothing and we’re all out of ideas”. By deprioritising human agency and the range of possible futures, they use determinism as a type of climate delay; something I call “predatory fatalism“. They have always sought to present the rapid replacement of fossil fuels as impossible, and they have always been catastrophically wrong (such as their insistence the 2010s-era “Renewable Energy Target” was impossible to meet, when it was comfortably exceeded). That they’ve been so shockingly wrong in the past seems to have no bearing on their perceived expertise on what’s impossible.

It is a refreshingly optimistic thing to observe. The skeptics, doubters and fatalists have been proven wrong. We are not bound to fossil fuels. But we are bound to the fact that there is no deterministic fate for this shift.