Dingo population estimates in Australia’s capital are so low a leading researcher is warning they could be on a “trajectory towards extinction”. At least four small packs roam across their last-known stronghold, the 106,095-hectare Namadgi National Park, but dozens are killed each year around its fringes through targeted trapping, shooting and poisoning.

A true population figure has never been known. But an ACT government camera survey between November 2024 and May 2025 concluded there are a minimum of 49 dingoes alive across the park.

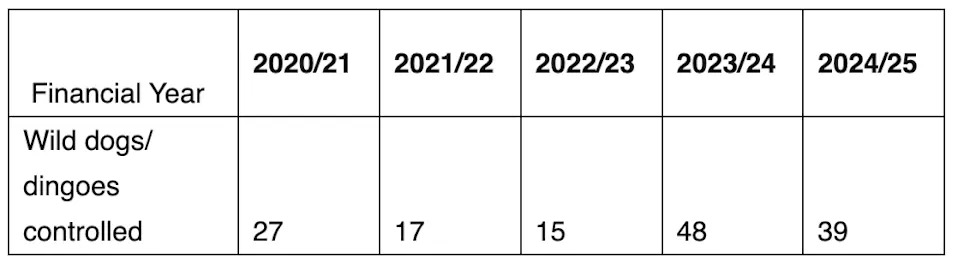

The number is suspected to be markedly higher than the government estimate, because its rangers have been killing dozens to limit their chances of attacking domestic sheep on nearby farms. Figures show they destroyed 39 inside Namadgi during the 2024/25 financial year and another 48 in 2023/24.

Professor Euan Ritchie, an ecologist at Deakin University, said even if the population was 100 animals, and 87 were killed over two years, then this would be “an astronomically high rate of mortality and diabolical for the ongoing survival of dingoes in the ACT.”

He suggested another possibility is the population is being replenished by dingoes in neighbouring areas, like NSW’s Kosciuszko National Park. Until a more certain figure is known, he has urged caution in how dingoes are controlled.

Related: 🌏 Aussie island that could hold ‘secret’ to why beloved animal is vanishing

Fluctuating numbers of dingoes have been killed by the government inside Namadgi National Park. Source: ACT Government

New insight into dingo populations in national park

To compile a more accurate dingo population estimate, the ACT Government is working with the University of NSW. Leading that work is PhD student James Vandersteen, who has shared early insights into the data he’s analysed from three valleys, using dozens of cameras, between July 2023 and January 2024.

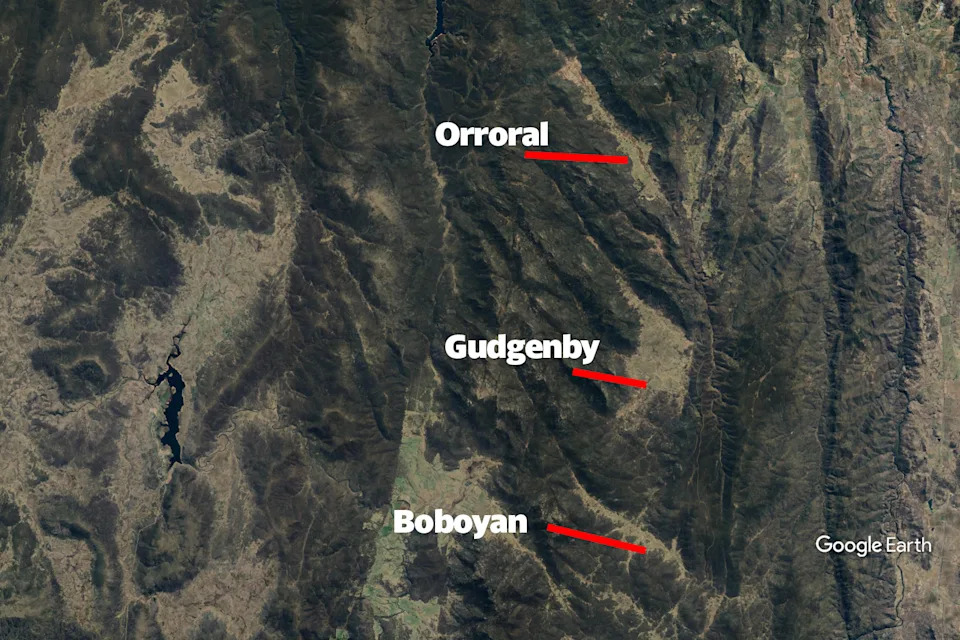

Dingoes are known to roam the forests and smaller clearings. But it’s thought the majority are found in three large low-lying grassland valleys, and so that’s where he’s conducted his surveys. “There’s definitely a lot more kangaroos in the valleys, and the terrain is a lot easier for them to traverse. The forested sections are massive mountains, so hunting in that kind of habitat wouldn’t be very successful,” Vandersteen told Yahoo.

James Vandersteen has set camera traps in three valleys, where most of the dingoes in Namadgi National Park are thought to live. Source: Google Earth

Inside the Boboyan valley, on the NSW border, Vandersteen’s cameras have recorded at least 18 individuals, and using a statistical modelling system called “spatially explicit capture-recapture”, he has an early estimate of 40 dingoes living there.

Northeast of a mountain in the Gudgenby valley, Vandersteen has sighted around 12 dingoes. But most haven’t been captured on his cameras, and so he’s unable to estimate a minimum number of individuals using modelling.

Further north is a long valley named Orroral that was home to a NASA tracking station until it was decommissioned in 1985. Today, the lower half of the valley is a popular camping spot with a lot of human activity, so dingoes are wary, and none were detected.

The upper side of Orroral is only accessible on foot, and 10 were captured on camera, with modelling suggesting around 60 individuals live there.

Dozens of cameras have been set up across each valley to monitor for dingoes. Source: James Vandersteen/UNSW

How many dingoes is healthy for an ecosystem?

Packs and lone roaming individuals have shown fidelity to their valleys. Because of the abundance of food and water, they don’t need to roam large areas like desert dingoes do.

Vandersteen said it’s not yet known what population size would be considered healthy, and there’s “still quite a lot to learn.” He’s working to understand how their presence affects the wider natural ecosystem. Particularly how they’re suppressing invasive foxes and cats, so small mammals and marsupials can flourish, and how they keep kangaroo numbers in balance.

“Maybe there are problem dingo areas where they’re taking out a sheep or two, but the key thing that we want to maintain is their ecosystem function and their role as an apex predator,” he said.

Most dingoes in ACT are pure

Despite dingoes playing an important environmental role and having cultural significance, the ACT Government, like other states and territories, has treated them as a pest. Authorities have traditionally referred to dingoes as “wild dogs”, even though they are genetically distinct.

Recent analysis of dingoes in Namadgi by geneticist Dr Kylie Cairns has shifted thinking on their status in the ACT. Forty-seven tested as pure dingo, two had greater than 93 per cent dingo ancestry, and one was a domestic dog, which researchers believe likely wandered in from NSW.

In response, the ACT government has announced it is changing the dingo’s status from a pest species to a controlled native animal, similar to kangaroos, which it culls in the thousands.

Pure-bred dingoes naturally present in a range of colours, but there’s a misconception among the public that they should be tan-coloured. Source: James Vandersteen/UNSW

Controversial history of dingo control

The government’s history of culling dingoes has been contentious. In August, Yahoo News revealed it had been illegally using soft-jaw traps, which catch the animals by the leg, so they can be euthanised. In the 2024/25 financial year, 35 were trapped and four others ground shot.

The RSPCA has “significant welfare concerns” about the use of soft-jaw traps. It told Yahoo News “suffering is inevitable” as they cause pain and anxiety.

“Trapped animals can experience severe distress for many hours or even days and have been known to chew the trapped limb in a desperate attempt to escape. Leg hold trapping is indiscriminate and inflicts pain and suffering to any animal who is trapped including native and other non-target species,” an RSPCA Australia spokesperson told Yahoo.

The government itself had been concerned enough about their welfare impact to ban their use alongside shock collars and cockfighting spurs in 2019. But after questions were raised about why they were still being set to target dingoes, it created new legislation permitting their use on the species, and in the process, it controversially did not consult with its Animal Welfare Advisory Committee.

ACT urged to learn from Victoria’s dingo failures

The government is now in the process of drafting a new Dingo Controlled Native Species Management Plan, and it has vowed to consult widely.

As an expert in Victoria’s dingoes, which are listed as threatened with extinction due to ongoing culling and habitat destruction, Professor Ritchie is urging caution.

In the Big Desert-Wiperfeld region, in the state’s northwest, he estimates just 80 adults remain. This has led to high rates of inbreeding and low genetic diversity and he warns they are “likely well on their way to extinction”.

When it comes to the ACT population, he believes authorities should adopt a conservative approach to their management, to ensure the same problems experienced in Victoria aren’t repeated.

“Until a robust population estimate of dingo numbers in Namadgi is available, it is simply not possible to reliably know the true impact of government dingo culling programs on their population numbers, and hence, a precautionary, conservative approach would seem very sensible,” he said.

Love Australia’s weird and wonderful environment? 🐊🦘😳 Get our new newsletter showcasing the week’s best stories.