Energy, not algorithms, will decide who leads in artificial intelligence. At the AI Horizons Summit in Pittsburgh last week, the United States’ largest natural gas producer, EQT, made the case bluntly: the real contest is between Chinese coal and American natural gas. For Australia, to achieve our own AI capability, we must anchor it in our own energy, and the gas-rich but largely undeveloped Beetaloo Basin presents an opportunity.

The Pittsburgh summit reframed the global AI race. No longer just about chips, models, or algorithms, it is also about the energy required to power them.

China added nearly 60 gigawatts of mostly coal-fired power capacity last year, almost 10 times as much as the US did. Its grid is already twice the size of the US’s and growing twice as fast. In this telling, America’s comparative advantage isn’t its chipmakers or start-ups but its gas: abundant, dispatchable and faster to market than nuclear or large-scale renewable energy sources. EQT chief executive Toby Rice went so far as to argue that the cost of power is now the cost of intelligence. And the price of energy in Australia is currently too high for us to compete, an ironic fact given our status as an energy exporter.

Pennsylvania has seized the moment. Once synonymous with coal and steel, Pittsburgh is being deliberately rebranded as a computing hub, where abundant shale gas in the Marcellus Basin converges with Carnegie Mellon University’s AI talent and heavy AI and energy investments. A US$20 billion Amazon data centre, a gas-powered one in Homer City and bipartisan political alignment have turned natural gas into a national security asset.

What Pennsylvania is doing for America’s AI ambitions, the Beetaloo Basin can do for Australia.

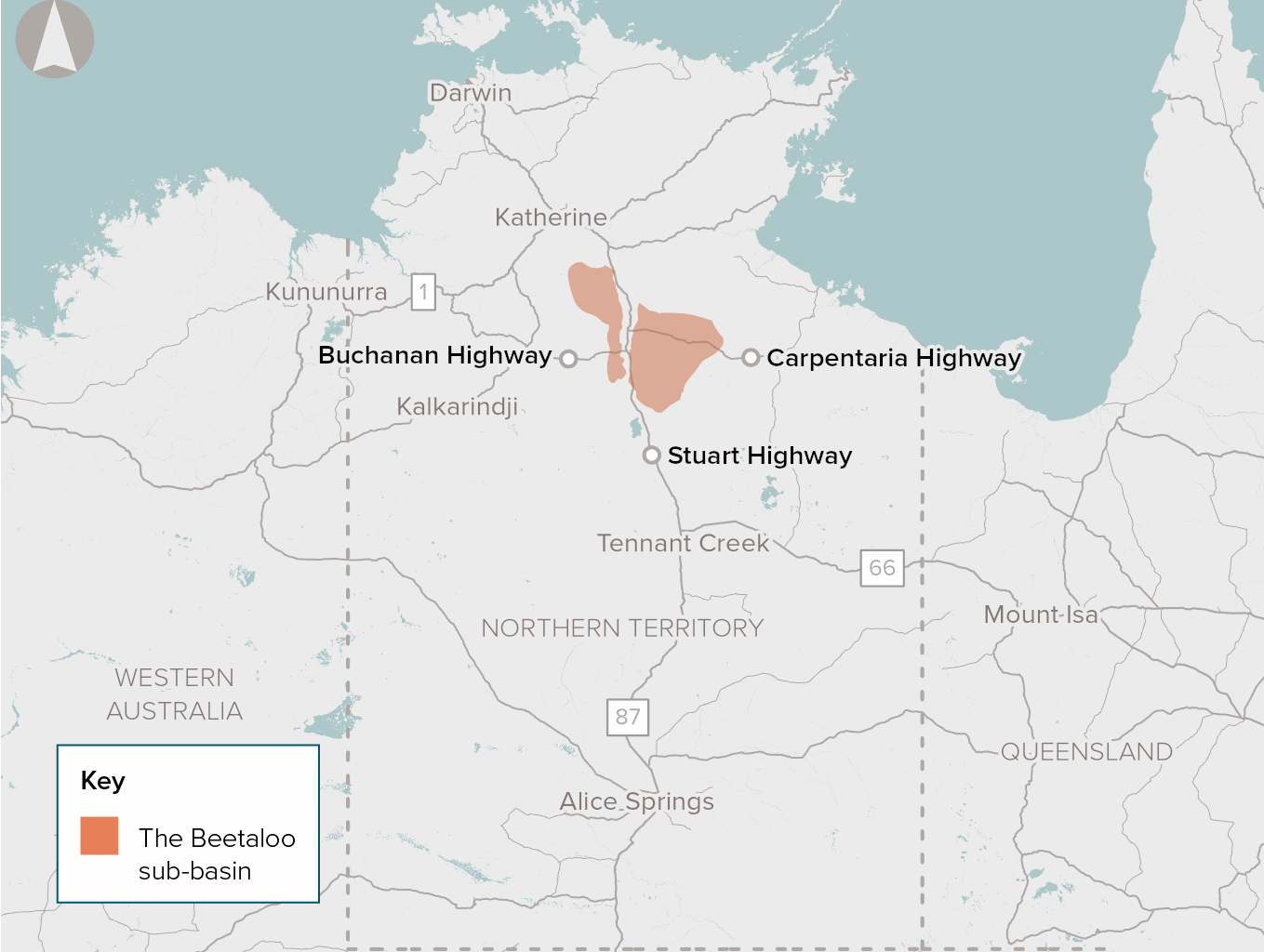

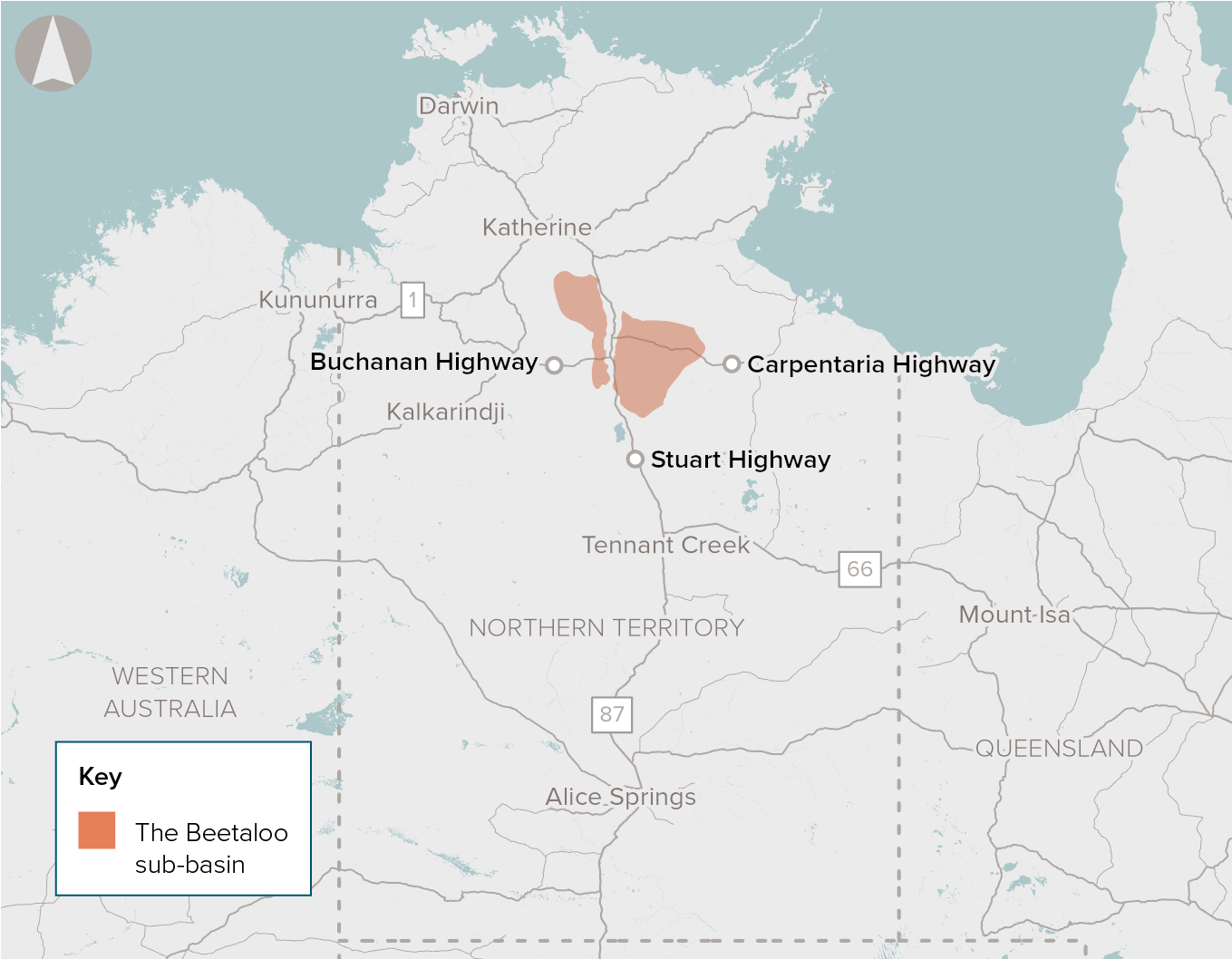

The parallels are obvious. The Beetaloo, also called a sub-basin, has scale, location and strategic alignment. Darwin, less than 500 kilometres to the north, is already a gateway for defence logistics, subsea cables and digital infrastructure. Just as Pittsburgh is recasting its shale gas as the foundation of the US’s digital revolution, the Beetaloo can be framed as Australia’s major computing zone.

This requires moving beyond the old logic of liquefied-natural-gas exports or balancing domestic supply. Instead, Beetaloo gas can underwrite Australia’s digital sovereignty: powering AI data centres and enabling critical industries. As renewables and nuclear energy scale over time, gas can provide the speed and reliability required by computing-intensive systems currently.

Critics will argue that this locks Australia into fossil fuels. They’ll be right to raise concerns about emissions. But the answer isn’t avoidance but abatement. Carbon capture, offsets, and tighter methane standards must be built into Beetaloo-linked AI projects. The Pittsburgh message wasn’t that gas replaces renewables but that without gas there’s no bridge to a reliable AI future. Wind, solar and batteries cannot yet meet the unrelenting demand curve of data centres running frontier AI models. Gas, with lower emissions intensity than coal and proven scalability, provides the necessary buffer.

The more pressing challenge is regulatory, not financial. Both in the US and Australia, capital is ready to flow. In Pennsylvania, more than US$90 billion has already been committed. As Rice made clear, the bottleneck is getting permits, not financing. America is beginning to respond with deregulation and incentives for reliability as well as emissions reductions. Australia must follow suit. If we delay, investment and computing capacity will flow elsewhere in the region.

The way forward for Australia is clear. First, frame the Beetaloo in AI terms and position it as the enabler of sovereign AI capability and digital resilience, not just another gas basin. Second, engage policymakers directly and make the case that Beetaloo’s role in powering AI aligns with national priorities in defence, critical minerals, and northern development. Third, demonstrate with pilot projects: a Beetaloo-based gas-to-computing project, tied into Darwin’s digital infrastructure, could provide proof of concept and attract private and allied investment.

This isn’t about sidelining renewables. On the contrary, Beetaloo gas should be integrated into a broader energy mix that accelerates Australia’s net-zero trajectory while ensuring immediate reliability for compute. The choice isn’t between gas and renewables but between having sovereign AI capability or relying on others who often use higher-carbon, energy-intensive methods.

The contest for AI dominance is as much about kilowatts as it is about code. In Pittsburgh, the US began to frame its AI strategy around energy. Australia has the opportunity to do the same, but only if we take decisive action. The Beetaloo Basin can anchor our AI future in our own energy and our own computing capacity.