Björn Borg is part of tennis folklore. He won 11 Grand Slam titles — six French Opens and five Wimbledons — and transformed the sport in the 1970s and 1980s with his style on and off the court. With John McEnroe, he formed one of the greatest rivalries in tennis history, the Swedish “Ice Borg” to the American’s fire, before retiring burnt-out in his mid-20s, despite McEnroe’s pleas that he continue.

So what then happened to a player who, by his own admission, has always been a closed book? Ahead of turning 70 next year, Borg wants to tell his story. “I had a big backpack on my back. I wanted to throw that away,” he said in a video interview last month, ahead of the release of his autobiography, “Heartbeats,” on September 18 in the UK and September 23 in the U.S.

Borg opens up on his relationship with his parents, various partners and his children, as well as his partying days centred on the legendary New York nightclub, Studio 54. As reported by The Athletic earlier this month, he reveals that he has been living with a prostate cancer diagnosis, and that a reliance on drugs, pills and alcohol in the years after he quit tennis brought him to his lowest ebbs, including two near-death experiences in the 1980s and 1990s.

“I was lost in this world,” Borg said of the period after he officially left the sport in January 1983. “I didn’t have any help. I didn’t have a team or agents to push me in the right way. I did everything by myself, I didn’t really have any help during that time and it’s very tough to fix yourself.”

Borg’s unflappability and success on the court made it seem that little bothered him. He was impossibly cool, with his good looks and fashionable Fila kit, an aesthetic that made him one of sport’s first true global superstars.

But his fame, attendant hysteria, and a sport which wasn’t really ready for its transformation from “being a classic sport that bordered on being a bit stiff and boring to becoming incredibly popular, with us tennis players transforming into heroes and teen idols” weighed on him more than he then let on.

“I never express my feelings. You could see myself when I was playing tennis. I didn’t open my mouth,” he said.

“I’m a Gemini, I am two people. If one sleeps, the other one goes out. And this devil on my shoulder, he tried to put me down so many times.”

Borg was generally able to keep the devil on his shoulder quiet during his playing career. He was one of the first players to really worry about diet and sleep, and claims to be the first to have a full-time coach (Lennart “Labbe” Bergelin, who died in 2008) traveling with him. Bergelin also gave Borg regular sports massages, which at the time was revolutionary — likewise the meditation and yoga Borg started in the early 1970s.

Borg also used less conventional methods to get an edge, like working with a medium after a heartbreaking U.S. Open loss in 1979. In “Heartbeats,” Borg writes: “She told me the stars were never aligned for me at the U.S. Open, and that I’d never win there, and I never did. It was eerie how accurate she was. But I was hooked, and I kept working with her for the next three years.”

During his reign at the top of the sport, which took in five straight Wimbledons between 1976 and 1980, Borg also needed a release from time to time, and lived a glamorous lifestyle during a golden age for tennis characters. McEnroe, Jimmy Connors, Ilie Năstase, and Vitas Gerulaitis were among the giants of the sport at the time, and while Borg’s relationship with McEnroe has been discussed ad nauseam, Gerulaitis is arguably more important to Borg’s story.

The American was a constant source of support for Borg, and opened doors to the celebrity world that centered on New York’s Studio 54. Borg would stay at Gerulaitis’ pad in Long Island, where he had a court that matched the surface of the U.S. Open, and from there the city was their oyster.

Björn Borg celebrates after beating John McEnroe in the 1980 Wimbledon final. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Borg recounts mixing with stars of the New York social scene like now-President of the United States Donald Trump, who was a tennis fan and would come and watch Borg and Gerulaitis in New York. Paul Simon, Aerosmith, Elton John, Rod Stewart, Sting, Tina Turner and Mick Jagger were just a few of the artists Borg recalls hanging out with, but he said that while he was still a player, Studio 54 was more of a break from how structured the life of a professional athlete was than an invitation to party to excess.

It was after he stopped playing, in 1982, that the devil on his shoulder took over. After a 1981 U.S. Open final defeat to McEnroe, who also beat him in the final of that year’s Wimbledon, Borg left Flushing Meadows before the trophy ceremony, went to a pre-arranged afterparty, and realised that this life was no longer for him.

“All I could think was how I didn’t belong in this world anymore,” Borg writes. “All I could think was how miserable my life had become. The thoughts grew heavier by the second, and suddenly, everything felt ice-cold and crushing.

“Now I knew there was absolutely no joy left in it for me.”

Borg started “self-medicating” through drugs and alcohol, first taking cocaine in 1982. In the ensuing years, the impact of his habits on his health worsened. In 1989, after the clothing business he had set up went bankrupt, Borg nearly died after taking a cocktail of drugs, pills, and alcohol in Milan.

He makes clear that it was not a suicide attempt; his second wife, the Italian singer Loredana Bertè, called an ambulance that saved his life. Borg had by then fathered a son, Robin, with Swedish model Jannike Björling, having divorced his first wife, the Romanian tennis player Mariana Simionescu.

Borg was racked by guilt about the impact of his actions on Robin, and an attempted tennis comeback in the early 1990s was an attempt to save himself. The comeback didn’t last long, one match (a defeat) in Monte Carlo in 1991, and then 11 more (all losses) in 1992 and 1993. His attempts to play with a by-now massively outdated wooden racket were tragicomic, but, as he put it: “If I don’t take that decision, maybe you and I will not be sitting here today talking.”

He trained in London, which he described as his “rehab.”

“I had a schedule, I was playing tennis again, I played so many hours in 1990 but I could not say one time to myself that I played good tennis,” Borg said.

It was after that comeback that, in Borg’s view, the devil on his shoulder came closest “to pulling me down to stay down all the time.” At a seniors event in the Netherlands in the mid-1990s, Borg suffered a heart attack and collapsed in front of his father, Rune, on a bridge. Björn, an only child who described his father as his “best friend,” still regrets letting him down. Rune died in the same year as Borg’s coach, Bergelin, which Borg described as “brutal”; Gerulaitis, his best friend in tennis, had died aged 40 in 1994.

“I wake up and I see my father in front of me. I was very close to dying. I feel so ashamed,” he said. “So embarrassed. Those kind of things, I don’t know why I do it. I’m just happy that I could think in a good way to change my life and enjoy my life again. That was very important.

“To be involved with drugs or pills or too much alcohol, that destroys, that’s the worst thing you can do. And that’s what I realized in the end. I had to change my life. I could not continue doing this. That’s why I came back to tennis. But if I regret something, it’s just to try to be involved with these things I regret that so much because that’s so bad and that destroys you as a human being.”

Death has been a constant theme in Borg’s life. As well as the deaths of those close to him and the incident in the Netherlands, he twice nearly drowned while swimming in the sea. The title of the book is a nod to his heart stopping beating in that Dutch incident, and his low resting heart rate.

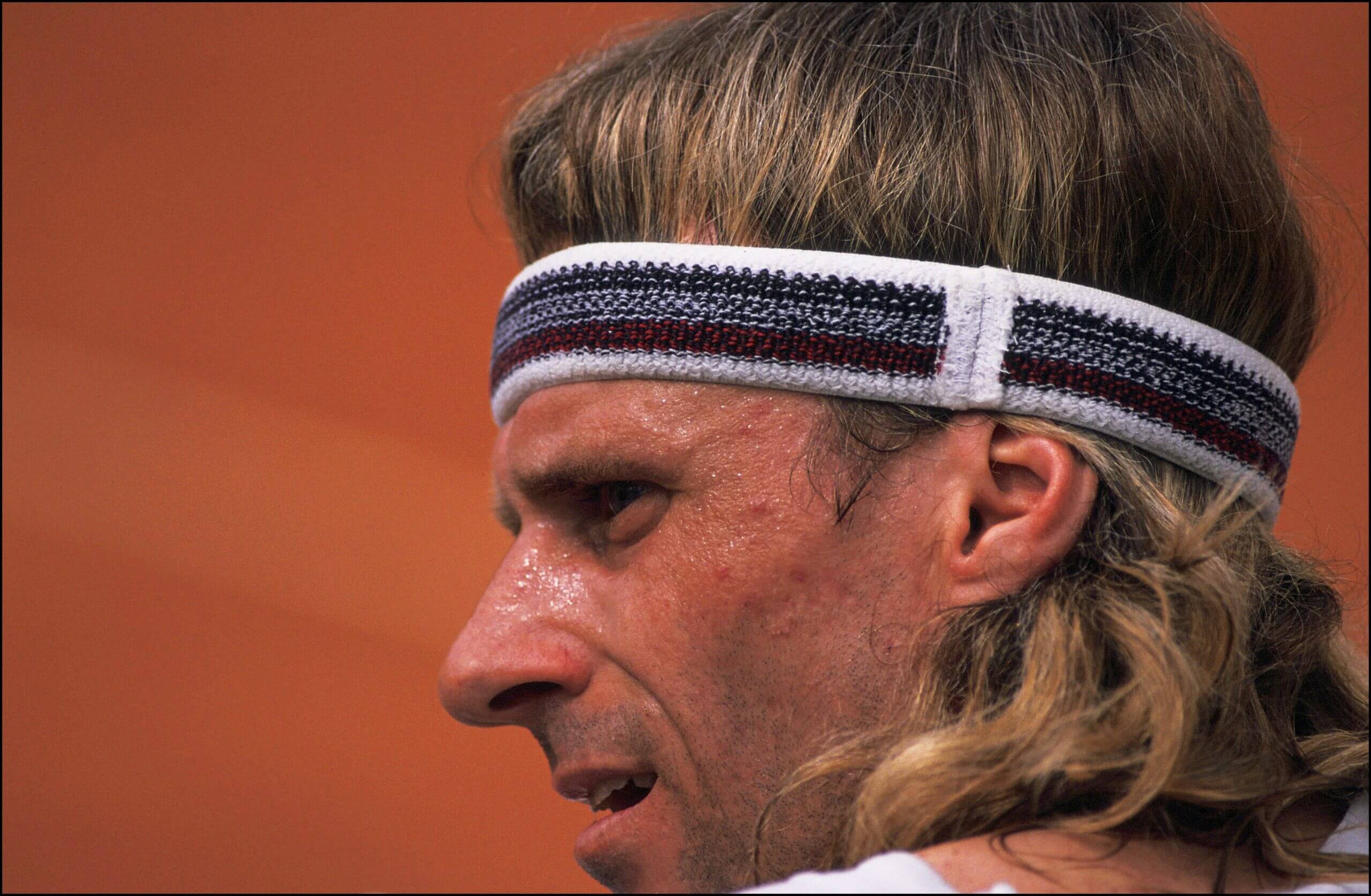

Björn Borg during his brief comeback in the early 1990s. (Jean-Pierre Rey / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Despite the wilderness that greeted the end of his career, Borg has no regrets about quitting tennis young, acknowledging things might have been different had he been playing in a different era. Security, and the cultural understanding of how fame impacts players off the court, have both changed dramatically in the past 45 years.

But those thoughts don’t bother him much. And even with the cancer diagnosis two years ago, and a subsequent life-saving operation in February 2024, he says he is in a much better place. He has regular checks every six months, the last of which was clear in August. He does push-ups and cycles every day in his living room in Stockholm, where he lives with his third wife, Patricia Östfeld.

They have been married for 23 years, with a son, Leo, who is professional player. Borg and Östfeld wrote “Heartbeats” together, after Borg had turned down numerous requests earlier in his life. When not in Sweden, they spend a lot of time in the Spanish island of Ibiza, but worked on much of the book, which took around two-and-a-half years, on the Cape Verde Islands off the coast of West Africa.

Borg still watches tennis regularly, enjoying the Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz rivalry and identifying Ben Shelton and Jack Draper as possible threats to their supremacy. “I love tennis,” Borg said. “I love to watch tennis. I’m not going to let tennis go, never ever, because that’s part of my life.

“It’s part of my heart to be involved with tennis, because it’s something I missed without realizing it when I stepped away. I hung around with the wrong crowds, the wrong people, but now I’m in the right moment,” he said.

Borg sometimes has such vivid dreams that he’s back competing that the bed shakes, and he remains in touch with old friends like McEnroe and Boris Becker, but misses his dad “terribly” and writes that he has a “strong sense” that Gerulaitis is “still with me, watching over me, and that he sees I’m finally happy.”

His hopes for the future, meanwhile, are simple.

“I have two beautiful sons. I have two beautiful grandchildren, aged 12 and 10. And I’m kind of a family man, and I want to spend a lot of time with the family. And that’s important for me,” he said.

Borg, whose nickname from a young age was “the jar” because of how he kept a lid on everything, hopes that after his book, “people understand me as a person,” as well as the tennis player of folklore who won all those titles as if carved from ice.

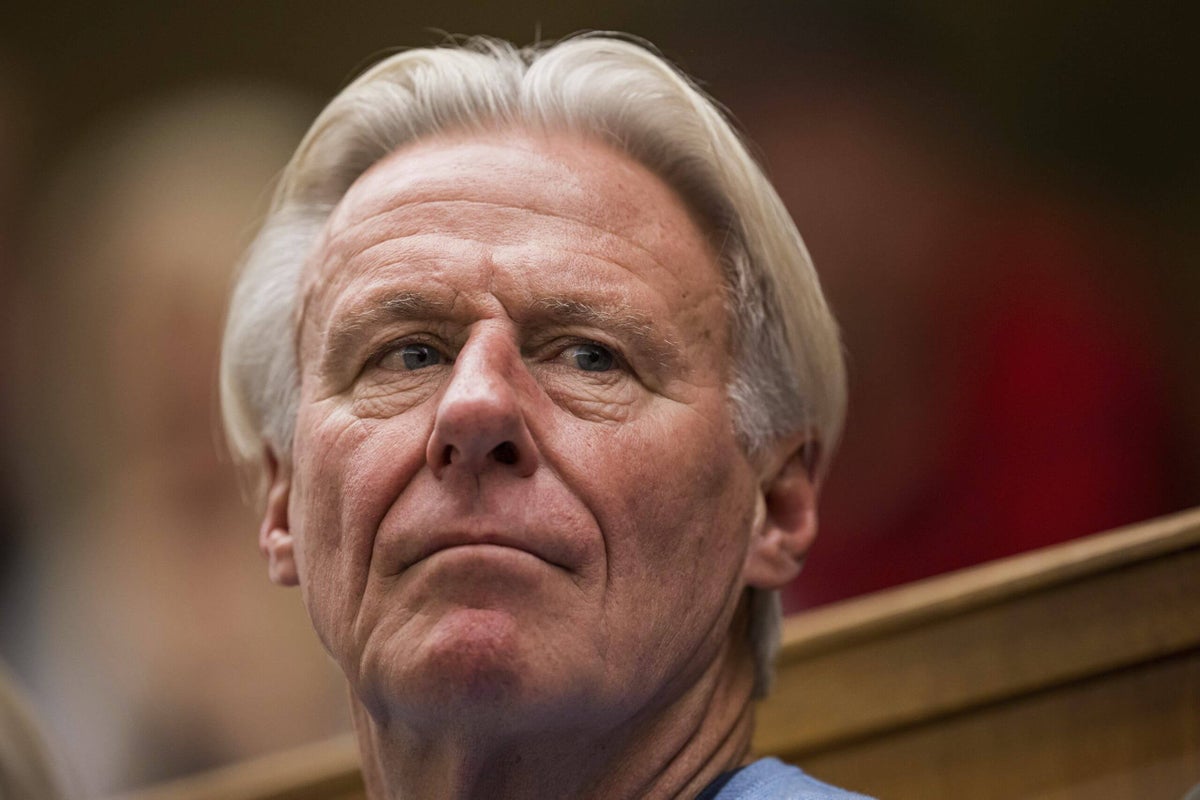

(Top photo: Jonathan Näckstrand / SIPA USA via Associated Press)