“My local beach is a few minutes’ drive away, so I surf there, come back to do a bit of work on the property and then play a bit of padel. Life’s good, mate.”

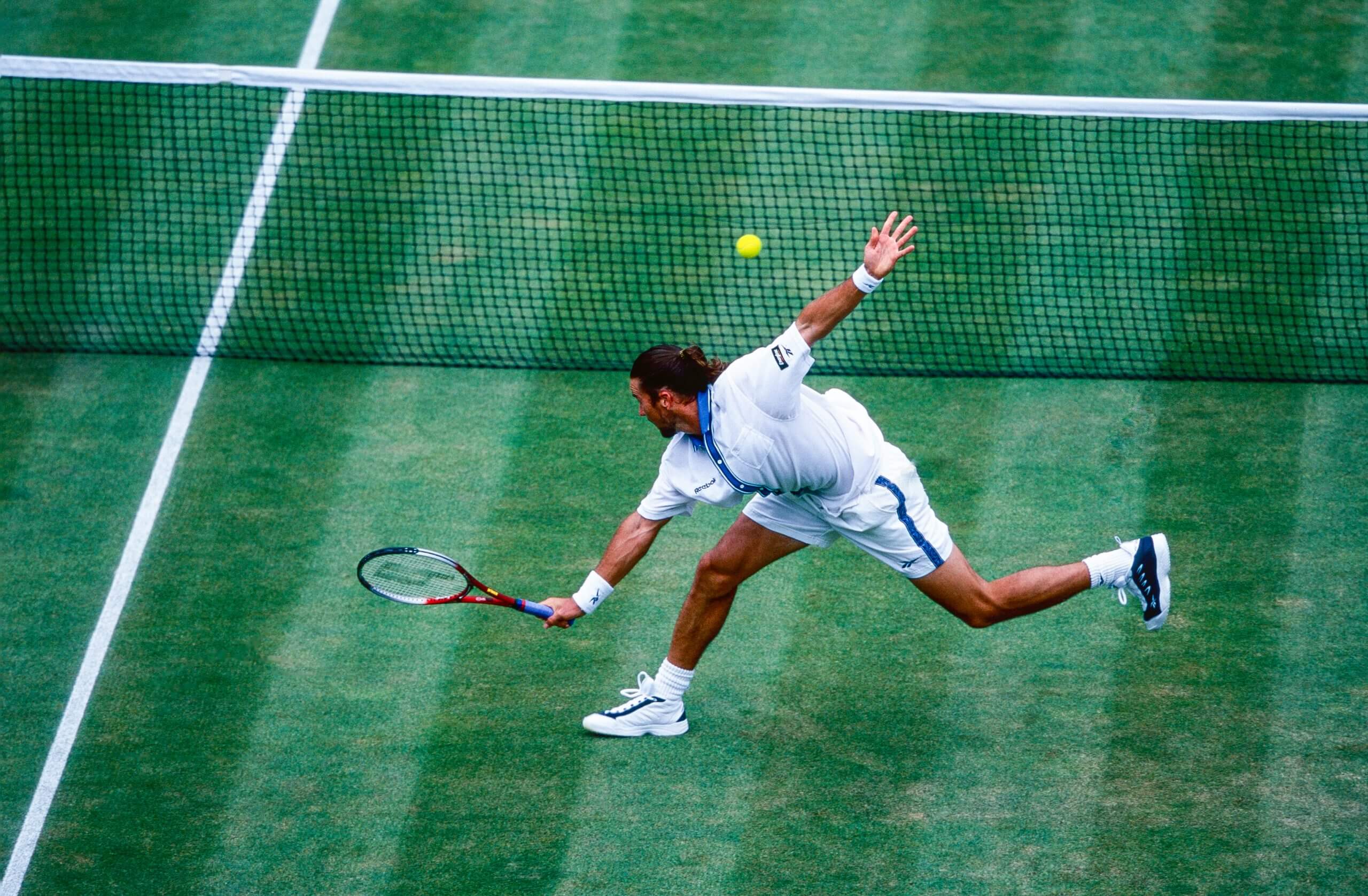

A smiling Pat Rafter is speaking from his 70-acre house next to Broken Head, south of Byron Bay, on the Australian east coast. Now 52, and 22 years removed from retiring from tennis, the former world No. 1 and two-time U.S. Open champion still radiates the kind of laid-back contentment that defined him as a player, when he thrilled crowds with his easy charm and swashbuckling serve-and-volley play.

Unlike many key characters of the 1990s and 2000s, traveling the world in the shadow of the sport that he once conquered holds little allure for the Australian, who invested extensively in property during and after his career. “My life here’s too good, mate,” he said. But he’s doing it now — at least for a few days — thanks to a call from one of his biggest rivals at the start of the year.

Rafter ran into Andre Agassi in three straight Wimbledon semifinals around the turn of the century, winning two of them before losing in the final on both occasions. Nine months ago, Agassi called his old rival in his role as captain of Team World at the Laver Cup, the annual three-day competition between a team composed of the best players in Europe, and one composed of the best of the rest of the world. Agassi invited Rafter to be his vice captain.

Pat Rafter with Andre Agassi in San Francisco at the Laver Cup. (Ezra Shaw / Getty Images)

Rafter and Agassi have remained friends since hanging up their rackets, and Rafter was pretty blunt in response. “It sort of depends, I guess, mate. It depends on how much work you need me to do,” he remembers saying. But the nature of their partnership appealed to him.

“It’s really important if you’re going to go into this type of job, whether it’s Davis Cup or Laver Cup, having that sort of yin and yang a little bit, and me and Andre we have that,” Rafter said — alluding not only to their different personalities, but to their opposite game-styles: Agassi the baseliner, Rafter the serve-and-volleyer.

“It makes it fun. I’m looking forward to the challenge.” They are even opposites in their chosen sport after tennis — Agassi made his pro pickleball debut this year, while Rafter is an international padel player.

“I find pickleball a really s— game of tennis to be honest,” Rafter said.

Rafter said he will take the lead from Team World’s players on the kind of guidance that they want. After U.S. Open and Davis Cup commitments for Taylor Fritz and Alex de Minaur, he thinks “it’s probably more about getting them in the right headspace and then freshening them up more than anything.

“If the players and everything want to try their ass off again and go hard, then we’re there for that as well, but we’ve got to really gauge them and try not pushing too hard as well.”

Part of the role of a Laver Cup captain is to act as a bridge between different eras. Rafter stopped playing just as men’s tennis underwent a major transformation. His final singles match was in 2001, when serve-and-volley was still a genuine strategy but rapidly becoming extinct. At that year’s Wimbledon, where Rafter lost an epic final to Goran Ivanišević, three of the four semifinalists were serve-and-volleyers.

The following year, there was just one, Tim Henman — Rafter’s counterpart on Team Europe at the Laver Cup — and even he was tending to stay back behind his second serves. A slowing down of the grass, heavier balls, and more powerful rackets meant that rushing to the net was rapidly becoming a fool’s errand, in London and on the rest of the ATP Tour.

“I just couldn’t believe some of the shots that were being made,” Rafter said.

“Some of the returns, that far back, hitting winners. If someone was standing that far back in the court, you do a kick serve, get to the net, and I just started getting passed everywhere. I was just thinking, ‘This guy is playing off his face.’ I didn’t know what was going on, but I couldn’t match these guys on a fast, hard court.

“I hit a big kicker, and then they’re just hitting winners from five metres behind the baseline. I remember even coming to volley and the ball was having a whole different ball flight. Just, wow, it’s different. No one had really spoken much about it, but the Europeans and South Americans were definitely onto it.”

Rafter was one of the last dedicated serve-and-volleyers to succeed at the highest level, and he’s sceptical about whether tennis will see another one. “There’s room for someone to mix it up to find a way to break rhythms,” Rafter said.

“But to actually play the real game, you need to do it at a pretty young age. There are subtleties and nuances hard to teach someone who’s 22 years old or on the tour. You’re not going to turn them into a full serve-and-volleyer like myself, (Stefan) Edberg, Cashy (Pat Cash), those types of players.

“If you look at the generation of people now, they all seem to be six foot six (198cm) at a minimum. And everyone serves absolute cannons and that’s not the way you serve-volley, where the idea is you hit the big kick serve to get to the net to get court position, so you can make your first volley. Serving massive serves and coming in is not really the way traditional serve-volleyers play because you’ve got less time to get to the net, the ball’s on you a lot quicker.”

Pat Rafter reached the Wimbledon final in 2000, then again in 2001. (Simon Bruty / Anychance via Getty Images)

Rafter maximised his understanding of these subtleties. He was a relatively late bloomer, having only won one ATP title anywhere before he won the U.S. Open in 1997, aged 24. McEnroe labelled him a “one-Slam wonder,” but Rafter defended the title the following year. As his profile grew after becoming a Grand Slam champion, Rafter was named People Magazine’s “Sexiest Athlete Alive” in 1997. “I’ve noticed you get better looking the more U.S. Opens you win and money you make,” Rafter said to GQ in 1999.

That was the year he became the world No. 1 — for a single week. In 2000 and 2001, he reached the Wimbledon final, losing to Pete Sampras and then Ivanišević, but his last singles match was at the Davis Cup final in November 2001. Rafter officially retired in January 2003.

“I was done — mentally, emotionally,” he said, having also managed arm, shoulder and knee injuries.

“I felt like I’d achieved pretty well everything, but more than that was the fact that I felt I needed something different in my life, and tennis had consumed so much of the first 28 years. The first year or two is a little bit tricky, because you have to come to terms with not being in the big situations and being in Wimbledon and those other places and vying for a position. But then you understand how much work’s required to actually be in there.”

The players Rafter will mentor at the Laver Cup have very different games from his era. Their lifestyles and approaches to the sport are different, too.

As Rafter puts it, in his day, “We had an absolute bloody ball.

“It was 100 percent different. Everyone’s got a camera now too, bloody hell, we would have been in trouble. That’s just a fact. I was a bit of a punk as well, I had fun. I am not gonna sit here and say I was a goody-goody two-shoes the whole time, everyone was there just having fun and drinking and doing stupid bloody things.”

Rafter mainly partied with his fellow Aussies, and said that “we just drank for four weeks” during the final weeks of the calendar because he “couldn’t deal with how miserable it was being indoors at the end of the year.” During a Davis Cup tie in 1997, he admitted to still being drunk for the dead rubber he had just won.

After his four Grand Slam finals, whether winning or losing, Rafter would put on a big party. In New York, following his U.S. Open wins, he would take over a back room at the Park Avenue Country Club in Manhattan and open it up for all the Australians and anyone who was around to join in the celebrations.

“We just drank until the sun came up, and I think I had one hour of sleep and went straight to do the trophy ceremony the next day in the park,” he said.

After his heartbreaking Wimbledon finals, Rafter would open the bar at the Dog and Fox in Wimbledon Village, where a few hundred people, mainly his compatriots, helped him commiserate. Rafter’s famous loss to Ivanišević in 2001 came by the time he was truly adored at home in Australia, unironically nicknamed Saint Pat, partly for donating around half of his U.S. Open winner’s prize money to children’s charities. So too was Rafter’s opponent, whose win as a Wimbledon wild card in his fourth final remains one of the sport’s ultimate feel-good stories.

There had to be a loser, and in a final held over to Monday because of rain and opened up to the public, Rafter lost a thriller in front of a frenzied, very un-Wimbledon crowd.

“Chaos. Total. Bloody. Chaos,” is Rafter’s summary of the day. And while he’ll be able to talk to his Laver Cup players about his successes and the fun he had on tour, he’ll also be able to explain what it’s like to suffer one of tennis’s biggest disappointments. Rafter was two points from winning the Wimbledon title he craved above all others, and though he doesn’t regret those specific points, it was a loss that took a while to get over.

His laid-back demeanor, and the fact that it was Ivanišević who won, made it appear that Rafter would be able to process the defeat as well as anyone. He did, but for five years after the final, Rafter would wake in a cold sweat thinking about what he might have done differently.

Does it still gnaw away at him? “Oh, not now,” he said. Adding with a smile: “It took about 20 years.”

At the time, he put on a brave face in the Dog and Fox: “I was dancing and cheering with everyone and singing songs and they carried you on your shoulders and all the Aussies and everyone’s s—faced drunk and laughing. Then you finish up there and you make your way home. I mean, what are you gonna do? I don’t know what else to do. I’m not gonna sit and cry in a corner.

“I was close. There’s only one winner out of 128, so I wasn’t good enough. That’s all it is.” Despite the relaxed personality, Rafter was known for giving absolutely everything on the court. “He’s just so dogged,” longtime commentator and broadcaster Mary Carillo told GQ in 1999.

“You cannot assume you’ve got him beat. You have to step on his neck and jump up and down on it. Then you’d better hold a mirror under his nostrils to be sure he’s dead.”

This fierce competitor has a very different focus at the Laver Cup: enjoyment. If his players have a good time, he will be confident that results will take care of themselves.

“Hopefully they buy into it as much as myself and Andre are going to,” he said.

(Top photo: Ezra Shaw / Getty Images)