Once dismissed as junk, Wood’s films now feel vital, stranger than ever and proof that even the ‘worst director of all time’ has a legacy worth taking seriously.Supplied

Will Sloan was seven years old when he first saw Plan 9 from Outer Space, Ed Wood’s infamous 1959 sci-fi oddity.

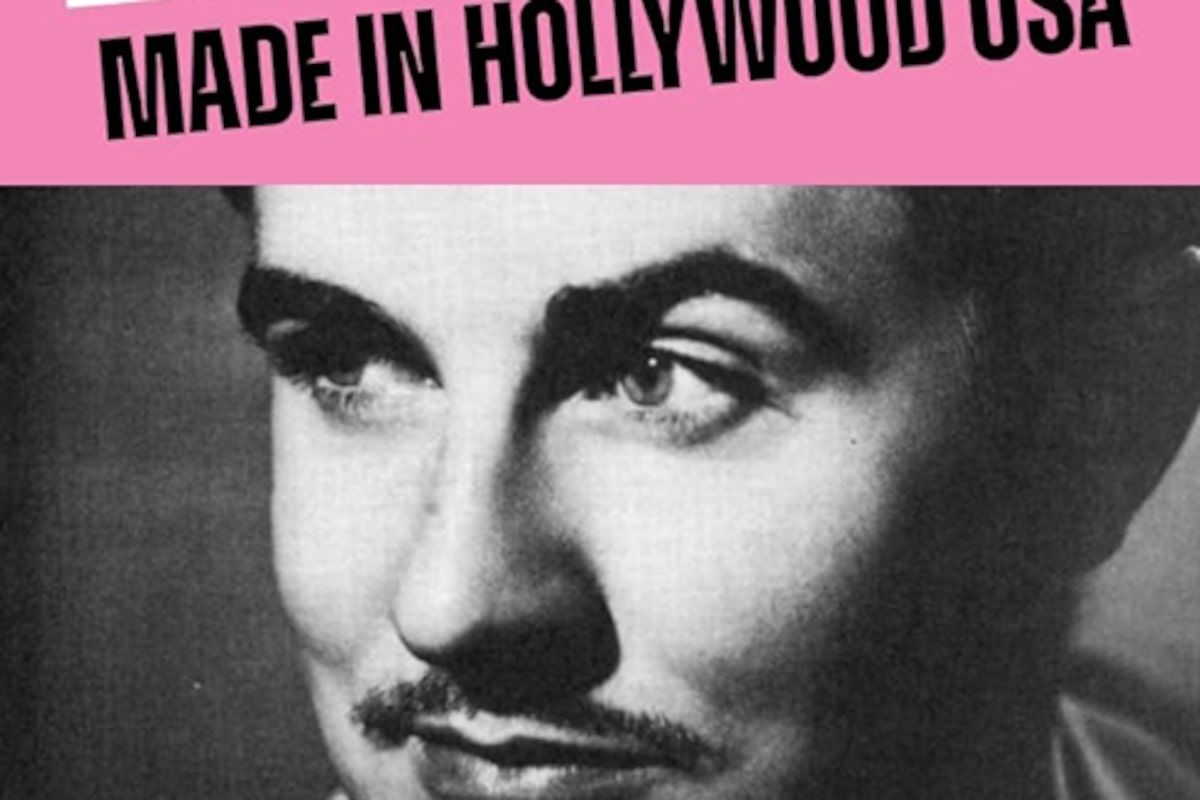

Now a journalist and film critic, Sloan has been touring North American cinemas and video stores to promote his new book, Ed Wood: Made in Hollywood USA, an empathetic, critical analysis of Wood’s body of work. Last week, he introduced Glen or Glenda? – Wood’s 1953 debut, a mix of mad-scientist schlock, docu-drama and personal confession about a cross-dresser’s secret life – to a packed house at Toronto’s Paradise Theatre.

The evening marked the culmination of a relationship with Wood’s films that began the day Sloan rented Plan 9 from his local library. Captivated by the cult filmmaker’s reputation as “the worst director of all time,” he laughed at the cheap effects and awful performances, but over time the novelty faded and something strange, even beautiful, emerged. “What remained,” Sloan writes in the book, “was its otherworldly oddness.”

Much of how we think about Wood comes not from the films themselves but from the mythology built around them. In 1980, Harry and Michael Medved’s Golden Turkey Awards dubbed Plan 9 from Outer Space the “Worst Movie Ever Made,” a punchline that froze Wood as a symbol of cinematic failure (sometimes to absurd extremes – in 1983, the Toronto Star’s Jeremy Ferguson dismissed David Cronenberg’s Rabid by calling him “the Canadian Edward D. Wood, Jr.”).

Will Sloan: Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal returns, with too much of a good thing

Fourteen years after the Golden Turkey Awards, Tim Burton’s biographical feature Ed Wood offered a more sympathetic lens, recasting him as a plucky dreamer played by Johnny Depp – hopeless in craft but heroic in his enthusiasm. The truth, as Sloan’s book argues, is stranger and more interesting: He was an artist working through personal obsessions in ways Hollywood, then and now, wasn’t quite ready to embrace.

Once dismissed as fodder for ridicule, Glen or Glenda? has since been embraced – particularly by LGBTQ audiences – as a pioneering, if complicated, queer text. Wood made the film in 1953 after persuading producer George Weiss to let him direct an exploitation picture inspired by the headlines around Christine Jorgensen’s gender-reassignment surgery. He convinced Weiss he was the right man for the job by offering up his own history with cross-dressing as the basis for the story – and by promising the involvement of horror legend Bela Lugosi.

“Seeing it with a modern audience has a very different vibe,” Sloan says. “You feel the audience wanting to like it and are sympathetic to Ed and the feelings he was expressing.” But it’s a complicated movie, he notes. “It is progressive to a point, but it also comes up against the limits of what was sayable in 1953 – and, I think, what Ed was willing or able to say to himself and others.”

The Paradise screening was part of the Drag Me to the Movies series hosted by drag artist Weird Alice, and that conflict was palpable, with moments of laughter and applause tempered by long silences. Sloan describes the experience as a roller-coaster ride, the crowd’s sympathy pulled up short by the film’s contradictions.

In attendance was film historian Willow Maclay, co-author of Corpses, Fools and Monsters: The History and Future of Transness in Cinema, who noted the joyous reaction to the film’s climax, when Glen’s partner, Barbara, accepts his gender fluidity and hands him her angora sweater: “I’ve always thought that was a very beautiful moment, and it was very nice seeing the crowd reaffirm that through their own reaction and applause.”

For Weird Alice, the point of screening a film like Glen or Glenda? is to create an environment where a messy, “of its time” artifact can be embraced in a space “where it’s potentially easier to stomach a more difficult subject matter.”

Notions of gender identity run through much of Wood’s work, from Glen or Glenda? onward. Sloan notes that Wood was fascinated by gender as performance: his male characters often cartoonishly masculine, his female characters sometimes bearing the name Shirley – Wood’s own drag persona.

What’s striking, Sloan argues, is how Wood himself seems to grow more at ease on screen. Glen or Glenda? is riddled with anxiety, a nervous plea for understanding. But by the late 1960s, in films such as Take It Out in Trade, long considered a lost film, where Wood appears as “Alicia,” he looks far more comfortable – even playful – inhabiting that side of himself.

Part of Glen or Glenda’s enduring fascination lies in its inconsistency. Because the film was long dismissed as disposable, what circulates today are incomplete prints – “some more censored than others, some more battered and beaten up by the projector and the winds of time than others,” Sloan explains. Each screening reveals a slightly different version, a scene appearing here, missing there. “Glen or Glenda? is a Hollywood dreamscape, a recurring dream that’s never quite the same.”

Although best known for his fifties-era films Glen or Glenda?, Bride of the Monster and Plan 9 from Outer Space, Wood kept working until his death in 1978, directing, writing screenplays and paperback novels under various pseudonyms, even appearing in a number of films. Of his later work in the burgeoning pornography industry – films like The Only House in Town and The Young Marrieds – there are still flashes of something rawer and more personal. Much of the work was unavailable for decades and has recently been restored by home video companies American Genre Film Archive and Severin Films. As Sloan argues, if you’re willing to accept Wood as an artist – not necessarily a great one, but an artist all the same – the later work only enriches the whole picture.

Sloan’s path with Wood traces how culture has shifted – from mocking his failures to searching out what’s personal, even moving, in his work. Once dismissed as junk, Wood’s films now feel vital, stranger than ever and proof that even the “worst director of all time” has a legacy worth taking seriously.

“The opportunity to show Glenn or Glenda? with the book is wonderful because really it is all about Ed. You know, I’m happy to bask in his reflected glory.”