Three million years ago, an extinct relative of todays’s great penguins – emperors and kings – lived in Aotearoa New Zealand.

We know this because our new study describes a spectacular fossilised skull of a great penguin found on the Taranaki coast.

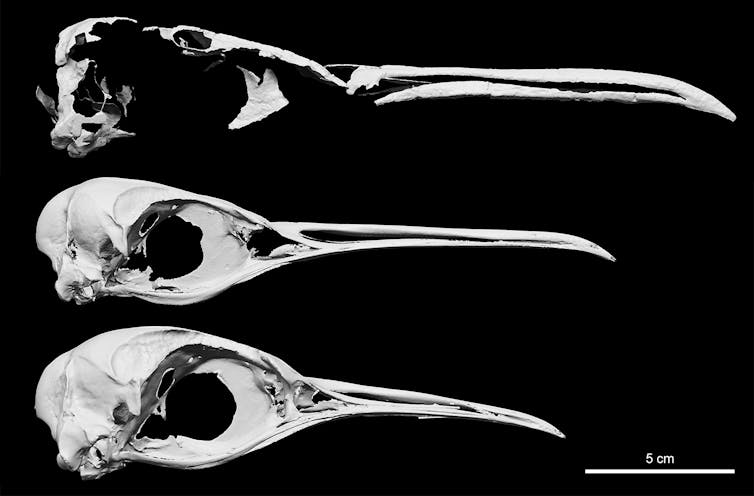

The fossil skull (top) of the extinct great penguin in its estimated original shape, in comparison with skulls from a king penguin (middle) and an emperor penguin (bottom).

CC BY-NC-ND

Overall, it is 31% longer than the skull of an emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri), which can be more than a metre tall and weigh upwards of 35 kilograms.

Compared to emperor penguins, however, the Taranaki great penguin had a much stronger and longer beak. It probably looked more like a king penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus), only much bigger.

At the time, the world was warmer than today. But when the climate cooled, this penguin vanished.

We argue the cold wasn’t to blame because crested and little penguins in New Zealand weathered the same change and remained. Great penguins shifted south and today live in the frozen wastes of Antarctica. So what drove their ancient relative to extinction?

Artist’s impression of the extinct great penguin that lived in New Zealand around three million years ago.

Simone Giovanardi, CC BY-SA

The sediments that now form beach-side cliffs in South Taranaki were deposited at a time when global temperatures were about 3°C above those of the pre-industrial era. Fossils from this period are transforming our understanding of how biodiversity might respond to rising temperatures.

For example, Aotearoa was home to box fish and monk seals, both of which are still (sub)tropical species today. In a strange contradiction, they coexisted with great penguins – now only found in much colder climates – in ancient New Zealand.

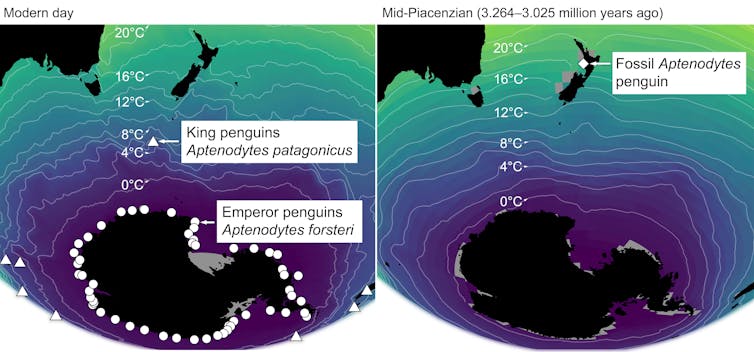

The northernmost breeding colonies of king penguins today are around latitude 46.1°S in the subantarctic Crozet Islands, where seawater temperatures reach 3-10°C. From there, it only gets colder towards the higher latitudes where emperor penguins live.

Today, great penguins are limited to subantarctic islands and the coast of Antarctica (map on the left). But ancient New Zealand was home to an extinct species of great penguin around three million years ago, during a period in Earth’s history known as the mid-Piacenzian Warming Period.

CC BY-SA

Three million years ago, Aotearoa’s great penguins extended as far north as 40.5°S, where South Taranaki was located then. They foraged in waters that were 20°C, much warmer than their relatives experience today.

This balmy existence ended with the Pleistocene ice ages around 2.58 million years ago. Ice extent and sea level shifted back and forward as temperatures fluctuated and ultimately ratcheted downwards. But why would such cooling eradicate giant penguins, which thrive under polar conditions today, from New Zealand?

Giant aerial predators

Fossil evidence for giant penguins in Aotearoa is limited and the exact reasons for their demise remain unclear. Even so, their sheer presence suggests they were less constrained by sea surface temperatures than previously thought. Another mechanism must be at play.

Up until about 500 years ago, Aotearoa was the hunting ground of the giant Haast’s eagle and the huge Forbes’ harrier. These were big raptors. They included large birds like moa in their diet. Their ancestors arrived from Australia inside the last three million years.

Based on what we see with living great penguins, the Taranaki great penguin almost certainly formed large exposed colonies along the coast. These could have been easy targets for a giant eagle or harrier hunting from the air.

By contrast, the smaller penguins still found in Aotearoa today have more cryptic breeding behaviour. They nest in burrows, natural crevices and dense vegetation, and tend to cross beaches at night, which may have helped them avoid aerial predators.

Predation on land is just one hypothesis, though, to help explain why these penguins became extinct in the region while others survived. Other possibilities include changes in the marine environment.

We know that reduced food availability can be devastating for penguins, but it is challenging to see why this would single out the great penguins.

Importantly, our study provides new insight into the habitat tolerances of great penguins. Both king and emperor penguins today can withstand temperatures up to 20°C higher than those they usually forage in.

Three million years ago, their relative experienced such warmth. As the world continues to warm, we need to remember that the geographic range of a species can change as circumstances change.

The marine ecosystem of Aotearoa will move into the habitable zone of many new species, making investigations of the last warm period more important than ever before.

We would like to acknowledge our research co-author Dan Ksepka from The Bruce Museum, Kerr Sharpe-Young for discovering the fossil, and Ngāti Ruanui and Ngāruahine for supporting the collection and research of fossils from their rohe.