Scientists recently sequenced Robertsonian chromosomes, the most common type of chromosome structural rearrangement in humans, and discovered specific sites where breakage and fusion occur.

Image credit:Grok AI-generated image, provided by authors

Robertsonian chromosomes are large chromosomes that form when the long arm of a chromosome breaks and fuses with another chromosome. They are the most common type of chromosome rearrangement in humans and are known to contribute to genetic disorders such as Down syndrome and certain cancers. However, scientists didn’t know how Robertsonian chromosomes formed or evolved—until now.

In a recent study, researchers sequenced Robertsonian chromosomes completely, telomere to telomere, for the first time.1 They discovered a common DNA breakpoint that leads to the formation of Robertsonian chromosomes. The team’s findings, published in Nature, provide insights into chromosome evolution and human genetic disorders.

“This is a landmark study,” said Glennis Logsdon, a genome scientist at the University of Pennsylvania who was not involved in the study, in a statement. “As the first group to identify the precise breakpoint at which Robertsonian chromosomes combine, [the researchers] have lit a flame that could ignite a broader understanding of how these chromosomes function.”

Continue reading below…

About a quarter of human chromosomes have off-center centromeres, which results in chromosomes with one long arm and one short arm. Sometimes, these long arms can break and fuse with another chromosome, forming large chromosomes with on-center centromeres. These are the Robertsonian chromosomes, named after the zoologist William Roberston, who first discovered these structures in grasshoppers in 1916.2

In the present study, the researchers sequenced three human cell lines: one derived from a clinically healthy individual, one from an individual with Down syndrome, and one from an individual who had experienced five miscarriages, indicating a level of reproductive abnormality. Each of these cell lines carried a common type of Robertsonian chromosome: the fusion of chromosome 14 with either chromosome 13 or 21. The researchers compared the sequences of these Robertsonian chromosomes to each of the individual chromosomes when unfused. Through this analysis, they discovered that DNA breaks and the long chromosome arms join at a region containing many repeated sequences, called SST1.

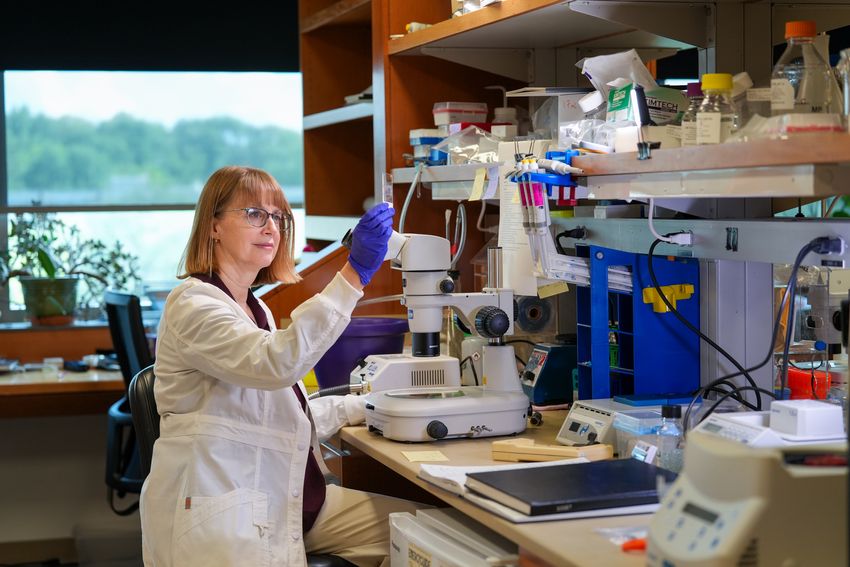

Jennifer Gerton, a cell biologist at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research, studies the interaction between proteins and chromosomes.

The Stowers Institute for Medical Research

“This is the first time anyone has shown where this exact DNA breakpoint occurs,” said Jennifer Gerton, a cell biologist at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research and coauthor of the study. “It opens the door to understanding how chromosomes evolve in a way that we had no appreciation for before.”

Gerson’s team also wondered how these large structural variants remained stable and how cells could transmit them faithfully as they divide. To answer this question, the team used fluorescent antibodies to visualize the chromosomes’ centromeres under a microscope. They also analyzed the centromeres’ activity using sequencing approaches. The researchers discovered that when chromosomes fuse, centromere activity is controlled epigenetically—sometimes through the complete inactivation of one of the two centromeres—to ensure that the microtubules attach properly as cells get ready to divide.

Gerton hopes that her team’s discovery about how Robertsonian chromosomes form and are maintained may help individuals with these structural variants make informed decisions about their future. The researchers also plan to investigate how sequences like SST1 influence the evolution of genomes as well as organisms.

Continue reading below…

“It really got us thinking about the role these repetitive DNA sequences play in shaping the genome and potentially creating new species,” said Leonardo Gomes de Lima, geneticist and evolutionary biologist at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research and coauthor of the study.

Gerton added, “It’s clear that there’s a story there, and that’s what we plan to study next.”