Objectives and research questions

The objectives of the study were to pilot the national versions of the OHL-Hos in hospitals from six countries: Austria (AT), Czech Republic (CZ), Germany (DE), Italy (IT), Norway (NO) and Serbia (RS), and to explore the feasibility of implementing the tool. Specifically, four general areas of feasibility were investigated, as described by Bowen et al. [23]: acceptability, implementation, practicality, and integration. The research questions were:

How do users experience the feasibility of the OHL-Hos and the self-assessment process (referring to acceptability, implementation, practicality and integration)?

To what extent does the use of the OHL-Hos enable the identification of OHL strengths and areas for improvement?

How does the use of the OHL-Hos support benchmarking among different national health care organizations?

While the first and second research questions were investigated empirically, the third question was only investigated theoretically in the discussion section.

Material: the OHL-Hos

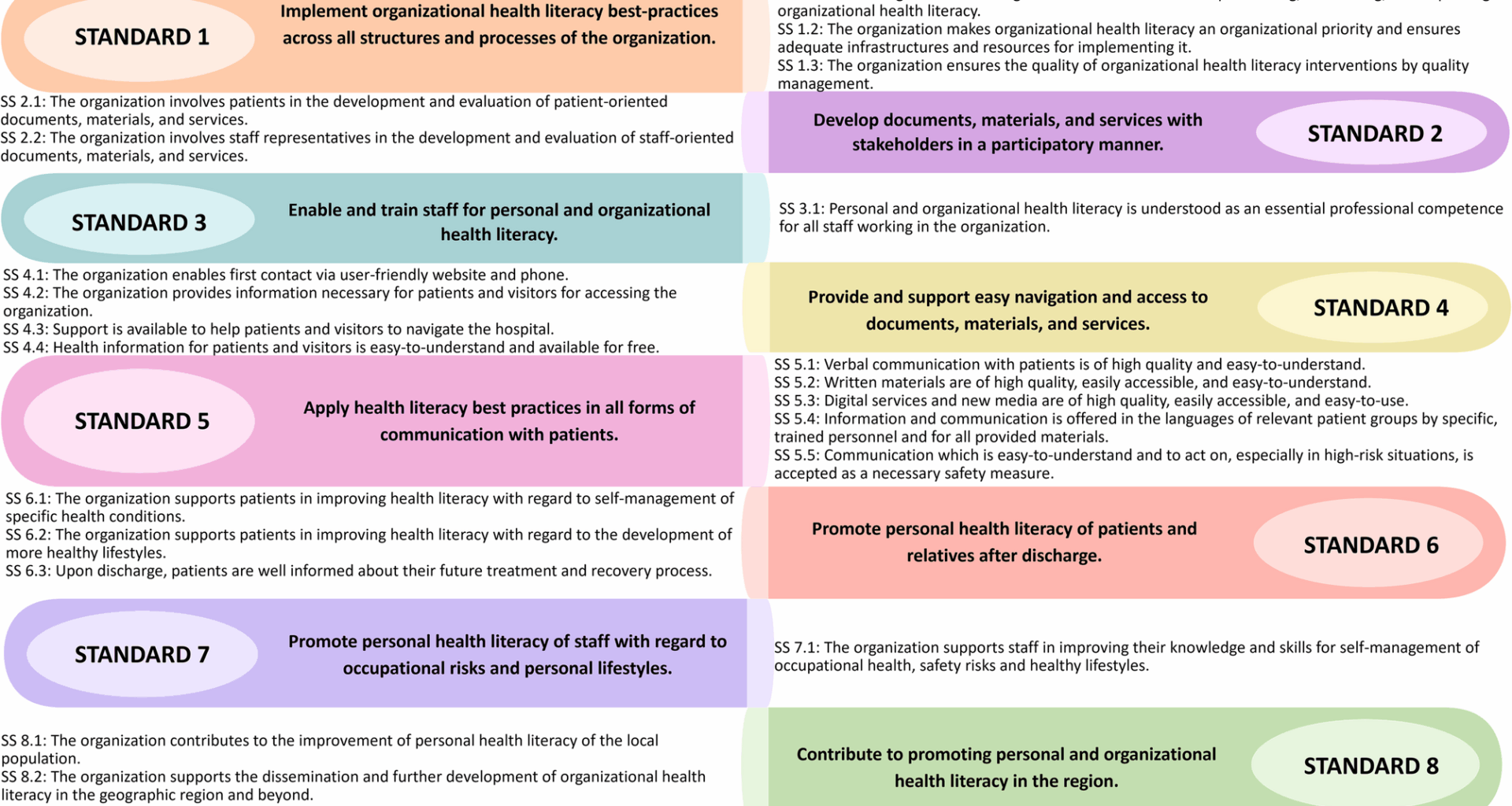

The OHL-Hos as used in this study is a modified version of the V-HLO-I. Like its predecessor, it is based on the Vienna concept as theoretical framework [19] and the definition of ‘health literate health care organization’ proposed by Pelikan and Dietscher [11]. The OHL-Hos acknowledges HL as a core concept of health promotion and relies on the health promoting settings approach. It is directed towards: (a) patients, (b) staff, (c) the resident population of the community a hospital serves, and (d) organizational structures and processes to implement the comprehensive OHL concept into the everyday practice of the organization across four domains (i) access to, living and working in the organization, (ii) diagnosis, treatment and care, (iii) disease management and prevention and (iv) healthy lifestyle development. Based on this framework the tool has eight standards and 21 sub-standards (Fig. 1).

Standards and sub-standards (SS) of the International Self-Assessment Tool for Organizational Health Literacy of Hospitals

The standards and sub-standards are operationalized by 155 indicators including sub-indicators, or 141 indicators without sub-indicators. The indicators operationalize concrete observable or measurable elements that are aligned with the principles for health care standards of the International Society for Quality in Health Care [24] and standards for health promotion in hospitals [25]. The underlying understanding of the earlier OHL debate in the United States of HL and OHL as a concept for improving the quality of health care services was considered, and accepted quality assurance methods in health care were explicitly applied [9, 11].

The OHL-hos is embedded in a comprehensive document with an introduction, background information on HL and OHL, and instructions on how to use the tool. Furthermore, a glossary and a template for an action plan are provided.

For each indicator, four categories indicating the degree of fulfillment are defined: completely fulfilled (76–100%) (‘yes’), fulfilled to a larger extent (51–75%) (‘rather yes’), fulfilled to a lesser extent (26–50%) (‘rather no’), or not fulfilled (0–25%) (‘no’). If a specific indicator is considered as not applicable (N/A) to the organization, it is categorized as such. For each indicator, the instrument offers additional space for comments that can explain or justify the self-assessment. The OHL-Hos is available at https://m-pohl.net/ReferencesOHL.

The self- assessment process

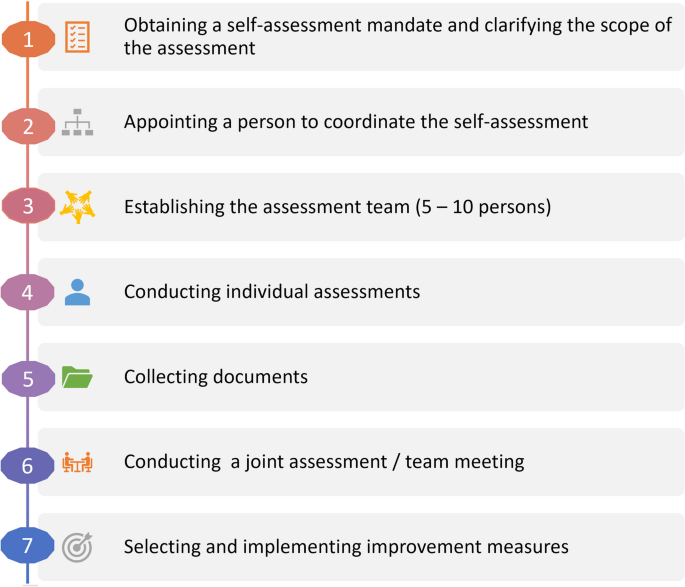

The instructions on how to use the OHL-Hos [22] recommends seven steps (Fig. 2). It starts with obtaining a self-assessment mandate from the responsible management of the hospital after clarifying the scope of the assessment (step 1). Next, the management should appoint a hospital-internal person to coordinate the self-assessment (step 2). An assessment team of five to ten people, ideally from executive management, quality management, health promotion, human resource development, medicine, nursing, therapeutic professions, building service/maintenance, patient-ombudsman/woman, self-help groups and patient representatives, and communications/spokesperson should be established (step 3). Each member of the assessment team should then provide an individual assessment completing the tool from their personal perspective (step 4). The individual assessments of all team members should then be captured on one table (excel-sheet), for ease of comparison and then be discussed in the following joint assessment (team meeting). Collecting documents, where possible, is suggested to assess some of the indicators (these are indicated with * in the tool) (step 5). This step should be seen as a supplement to step 4 and should take place simultaneously. In a joint assessment, the different individual assessments are brought together (step 6). It is recommended that a moderator be appointed to facilitate the discussion. In preparation for the joint assessment (step 6), the first step is to identify indicators with similar ratings. Then, the focus should be on indicators with significantly different ratings. The latter should be clarified and discussed during the joint assessment, leading to a diagnosis of the strengths and weaknesses concerning OHL of the institution or of the specific unit. On this basis, areas can be defined for selecting and implementing measures to improve specific aspects of OHL (step 7).

The seven steps of the OHL-Hos self-assessment process

A specific focus of this pilot study was on the feasibility of steps 3, 4, and 6 of the proposed self-assessment process, as inspired by the ‘RAND Appropriateness’ method [26]. According to this method, individual members of the internal multidisciplinary assessment team complete the questionnaire, after which the results are discussed in each service during a joint group assessment to achieve consensus. Step 5, collecting documents, was considered optional, and step 7 was considered beyond the scope of a pilot study.

Data collection and data analyses

The study was conducted within the WHO Action Network on Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy (M-POHL) [27]. In each country, a national research team coordinated the study on the national level and closely cooperated with the hospital-internal coordinator(s) and/or the participants from the selected hospital(s). The OHL-Hos was translated into German, Czech, Italian, Norwegian and Serbian following a common protocol suggesting two forward translations followed by a meeting to reach consensus on to the most appropriate version. Similar types of difficulties and challenges in the translation process were experienced, and similar strategies were used to address them (e.g. replacing original terms which were imprecise when translated with more precise terms). Next, all language versions of the tool were culturally adapted to the national context of hospitals and health care systems. Thereafter, the OHL-Hos was piloted in seven hospitals in six countries (Table 1). All hospitals included are non-profit organizations, except for the Czech hospital, which could be considered both a for-profit and a non-profit organization. The hospitals included from CZ, DE, IT, NO and RS are all government owned either regionally or locally, while the participating hospital in AT is owned by a religious organization (non-governmental organization). Six out of the seven pilot hospitals offer both basic and continuing education/ongoing training for the staff. One of the Italian hospitals offers only basic training.

Table 1 Characteristics of the participating hospitals

Piloting was performed in AT from October 2019 to March 2020, in CZ from April 2023 to June 2023, in DE from February 2023 to June 2023, in IT from September 2023 to July 2024, in NO from October 2022 to November 2022 and in RS from December 2023 to July 2024. The different timing between the participating countries is due to the fact that the first attempt to conduct the study was made shortly before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, and that the study was suspended during the pandemic.

A reporting template was developed to qualitatively and quantitatively document the process, results and experiences of the piloting by the research teams. The template included descriptive questions regarding the hospital in which piloting was performed as well as questions for assessing the feasibility and usability of the tool. When more than one pilot took place in a country, the template had to be completed separately. For each pilot there was close cooperation between the research team and the hospital-internal coordinators. The feasibility of the piloting process was assessed through direct observation of the joint assessment and semi-structured interviews (see supplementary file 1 for the detailed questions) with the internal coordinators within the hospital and/or directly with the participants either by phone or in person.

The reporting template also included numerical data from the self-assessment. To allow descriptive analysis of the pilot data, a numerical score was attributed to each response category (3 = yes, fulfilled completely (76–100%); 2 = rather yes, fulfilled to a large extent (51–75%); 1 = rather no, fulfilled to a lesser extent (26–50%); 0 = no, not fulfilled (0–25%); N/A = indicator is not applicable). N/A responses were treated as missing values for the analysis. In the NO pilot, the labels for the response categories were used slightly differently (fulfilled to a very large extent (76–100%), fulfilled to a large extent (51–75%), fulfilled to some extent (26–50%) and fulfilled to a small extent (0–25%) as the shortened ‘rather yes’ and ‘rather no’ were not well accepted when pre-testing the translation.

Calculations were performed for each pilot hospital separately. For each indicator, sub-standard and standard, means and standard deviations were calculated across all participants. The mean value of a standard was calculated from the means of each indicator within the standard for all participants. Sub-indicators were equally weighted as one indicator in the mean of the standard. Each sub-standard was weighted equally in the overall mean (= mean of a standard), regardless of the number of indicators in the sub-standard.

Using the results from the joint assessment, means were categorized into three groups, indicating: (i) areas of strengths (mean ≥ 2.0); (ii) areas of the intermediate stage needing attention (mean > 1.0 and < 2.0); (iii) areas of weaknesses (needing attention, mean ≤ 1.0). Standard deviations were categorized, indicating consensus level: (i) high (sd ≤ 0.75), (ii) medium (0.75 < sd < 1.0), and (iii) low sd ≥ 1.0).

Inferential analyses were not conducted due to the small number of participants (n = 7–24) from each hospital and that the data originated from only one hospital in five countries and two hospitals in another country.

Data were anonymized after the joint assessment (step 6) and before submitting it to the research team. General Data Protection Regulations’ compliance was ensured by all countries.