This is a far cry from the first subsea cables laid in the 1850s between England and France, with Europe and the US linked via telegraph in the 1860s. While brief messages took hours to decode, the cables opened a new age of intercontinental communication. Today, tools like ChatGPT rely on an ocean-spanning web of ultra-fast connectivity, fueling a wave of investment in new cables.

The stakes are massive: spending on cable systems is projected to surge to $15.4 billion by 2028, from $900 million in 2023, driven by demand for AI. And where cables land, you also find investment in data centers that are needed to manage and distribute the digital capacity that follows, creating hubs that amplify the economic benefits.

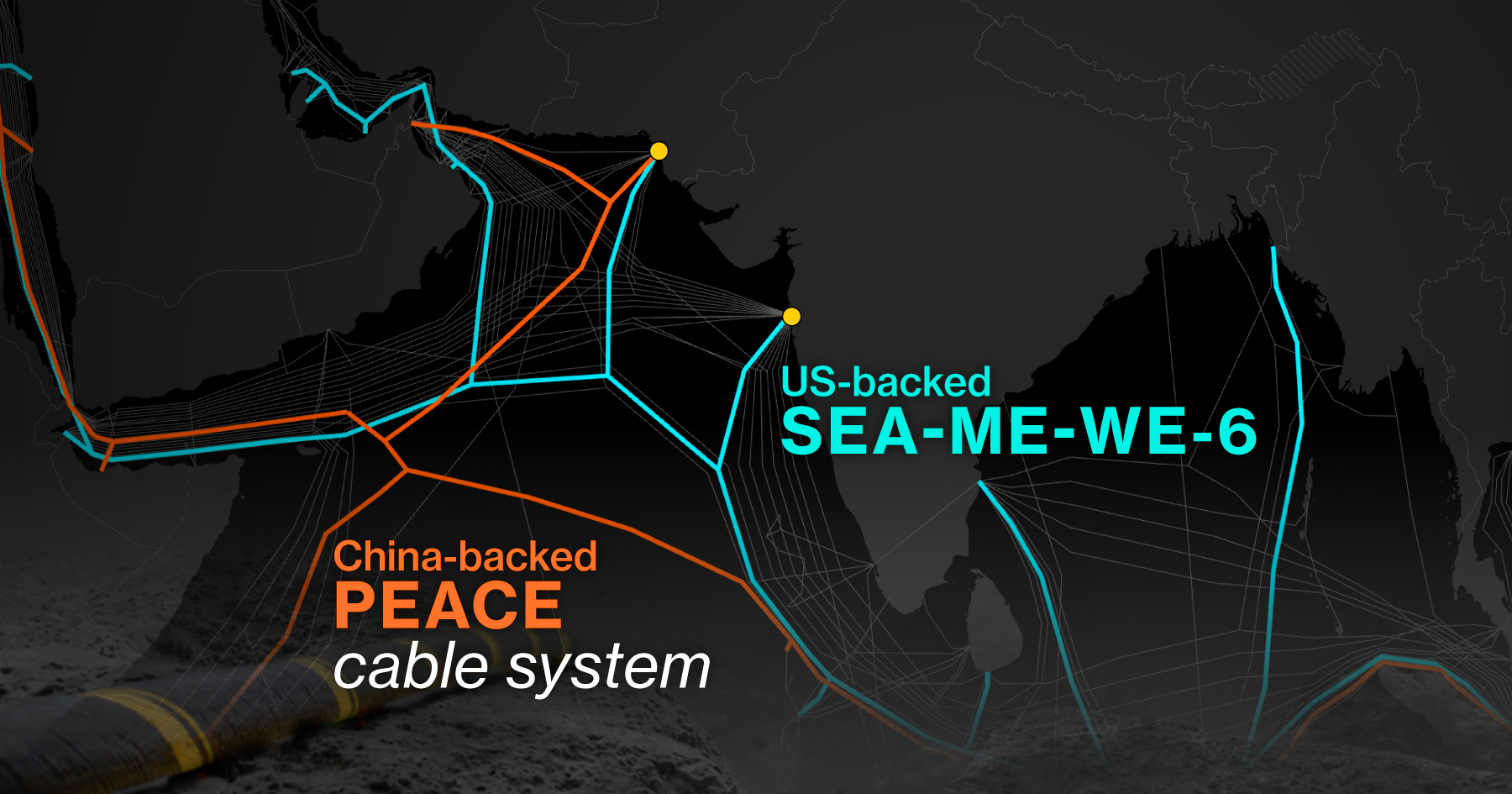

China has encouraged some countries to choose its cable network with financial support or cheap bids; firms like HMN Technologies can build them for 20% to 30% less than its rivals. Washington has countered with its own financial incentives, along with diplomatic pressure to dissuade strategically located countries, such as Vietnam, from depending on Chinese infrastructure.

China’s HMN Tech Plans to Build Three New Cables in the South China Sea

Source: TeleGeography

When the US-led SEA-ME-WE-6 consortium opened bids for its $600 million network in 2021, a US government agency reportedly offered training grants to telecom carriers that selected SubCom — over HMN Technologies — framing the move as a matter of national security. In August, the US communications regulator approved new rules to protect its subsea cables by barring certain Chinese equipment and restricting participation by foreign entities deemed security threats.

“The duel largely mirrors what we see in other areas of the global economy,” says Matthew Bloxham, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “The US and China are competing for influence over countries and regions that aren’t tied exclusively to either superpower.”

Governments worry about more than just strategic rivalry. Much of the global network lies unguarded and beyond the control of any single state, and physical access to cables allows not only for accidents — some 200 a year — but also for espionage, sabotage, and disruption. Even though there has been little direct evidence of wrongdoing, the sheer scale and exposed nature of the cable system has governments around the world scrambling to secure it.

The threat is “absolutely real,” says Trent Fulcher, CEO of Starboard Maritime Intelligence, an AI-powered platform that detects maritime security risks. In late September, he addressed a room of industry officials in Singapore, where the topic came up repeatedly over two days. Fulcher referenced certain incidents near Taiwan and the Baltic states. “Some of it is publicized, some of it isn’t.”

The Inside of a Subsea Communication Cable

Hover for more information

Source: TeleGeography

Note: Subsea cables are designed differently based on various ocean environments.

Landing points and shallow waters are where cables are most vulnerable, with the Hong Tai 58 incident underscoring the challenge of policing such zones. Collecting evidence and enforcing the law are difficult as “grey zone operations” — coercive acts that stop short of war but target weak points like undersea cables — can be disguised as fishing accidents, Taiwan’s Ministry of Digital Affairs told Bloomberg News.

Similar incidents in Europe and the Red Sea have raised further alarm. In December 2024, a ship departing from the Russian port of Ust-Luga dragged its anchor 90 kilometers across the Gulf of Finland, severing five data and power cables and inflicting at least €60 million ($70 million) in damage. In 2023, former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev warned on Telegram that if the West was behind the Nord Stream pipeline blasts in 2022, Moscow would have “no constraints — even moral — left” to destroy its enemies’ undersea cables.

How Damaged Cables Are Repaired

Source: KDDI Cableships & Subsea Engineering Inc.

Europe has responded by pouring money into new technologies. NATO has started using AI, deployed about 50 drones as part of its “Task Force X” initiative to track threats in the Baltic Sea and is weighing a similar program in the North Sea, according to a senior NATO official, who asked not to be identified as they were discussing internal plans. It’s also invested in a company that produces submersible robots that use 3D printing to repair damaged cables.

Last week, Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen warned Danes to brace for more hybrid attacks, including the destruction of subsea cables, pointing to Russia as Europe’s top security threat amid suspected drone sightings across Danish airports

China has also invested heavily in surveillance. In 2015, China State Shipbuilding Corp. announced plans for a network of undersea sensors — dubbed the “Underwater Great Wall” — across the South China Sea, where Beijing has also restricted foreign firms from laying new cables.

Defending cables has also become an arena ripe for private weapons manufacturers. According to Richard Jenkins, the CEO of US maritime defense company Saildrone, navies and coast guards don’t have enough manpower to fully oversee the protection of these cables. “That creates a huge vacancy for how we protect our oceans,” Jenkins says.

Cable Fault Causes

On an average, there are approximately 200 faults per year on global subsea cable systems

Source: International Cable Protection Committee

The business model for new cable networks is being upended. The consortia backed by traditional telecommunication firms that had come together to build cable networks are being overshadowed as US tech giants assert their dominance. Meta, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon are funding their own subsea cables to secure guaranteed bandwidth, reduce long-term costs, and ensure reliable global connectivity tailored to their cloud and data-intensive services.

Amazon, for example, has ramped up cable capacity through projects like CAP-1, while Google last year announced a $1 billion investment in digital connectivity to Japan, which includes subsea cables. Some argue that the biggest threat to the internet isn’t malicious activity, but rather a shortage of digital capacity.

“The real risk isn’t sabotage, it’s scarcity,” Meta’s global head of network investments Alex-Handrah Aime told Bloomberg News. “The reality is we need to create new corridors to connect these key areas and countries and regions of significant growth for Meta and we need to create more capacity to serve the AI age.”

By 2040, the total length of the subsea cable network is expected to increase by 48% as new routes expand to meet AI-driven data needs, industry reports show. Some worry that a new landscape dominated by big tech will create fresh vulnerabilities.

Installation of the SEA-ME-WE 5 submarine cable in La Seyne-sur-Mer, France, in March 2016. Photographer: Boris Horvat/AFP/Getty Images

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute think tank warns against the concentration of data — some of it sensitive — under the stewardship of just a few entities. “This digital supply-chain dependency risk, coupled with the volume of data that hyperscalers control across multiple layers of the internet services stack, heightens the risk of a single point of failure,” ASPI says.

Satellite networks such as Elon Musk’s Starlink are also growing fast, providing crucial links for land-locked countries and areas not plumbed into cable networks. While they offer a fallback if subsea systems fail, they’re nowhere close to a replacement.

Aitken, the retired British commodore who is now an associate researcher at policy think tank RAND Europe, says no effort is too small when it comes to protecting the modern economy’s critical infrastructure.

“In the Second World War, we bombed the hell out of roads and bridges, and in a coming conflict we shouldn’t be surprised if those cables become targets,” he says.

(Updates with warning from Denmark’s prime minister. An earlier version of the explainer corrected the description of undersea cable manufacturers and installers and amended the characterization of changes to the business model for new cable networks.)

Note: Mapped data from TeleGeography represents operational subsea cables and does not include planned cables except Meta’s Project Waterworth, — which is currently being built. Data as of June 17, 2025.

Additional Photography by: Ibrahim Chalhoub/AFP/Getty Images and Jean-Sebastien Evrard/AFP/Getty Images

Photos edited by: Yuki Tanaka Edited by: Malcolm ScottIngrid Fuary-WagnerShadab NazmiJeremy Diamond