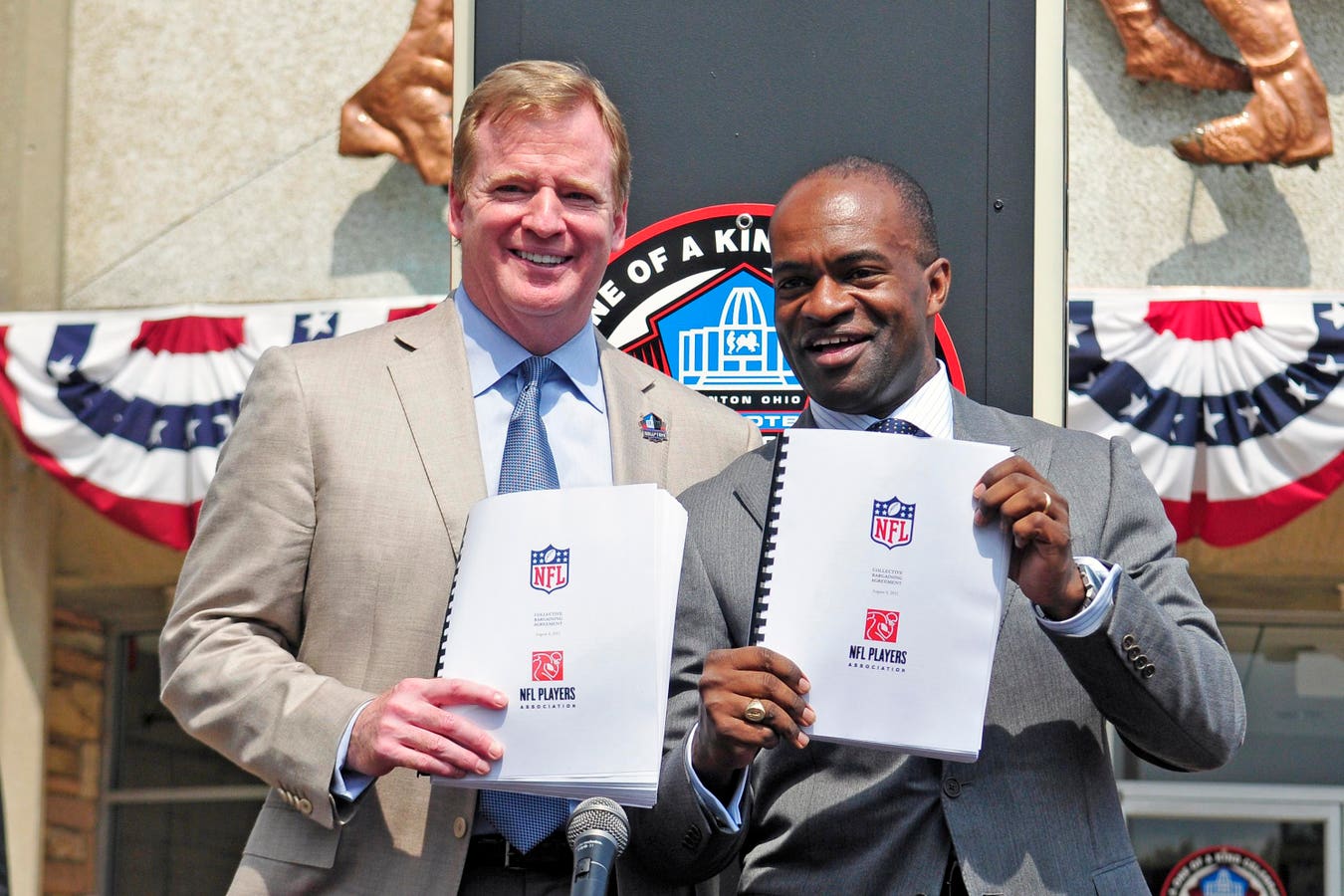

Photo by Jason Miller/Getty Images

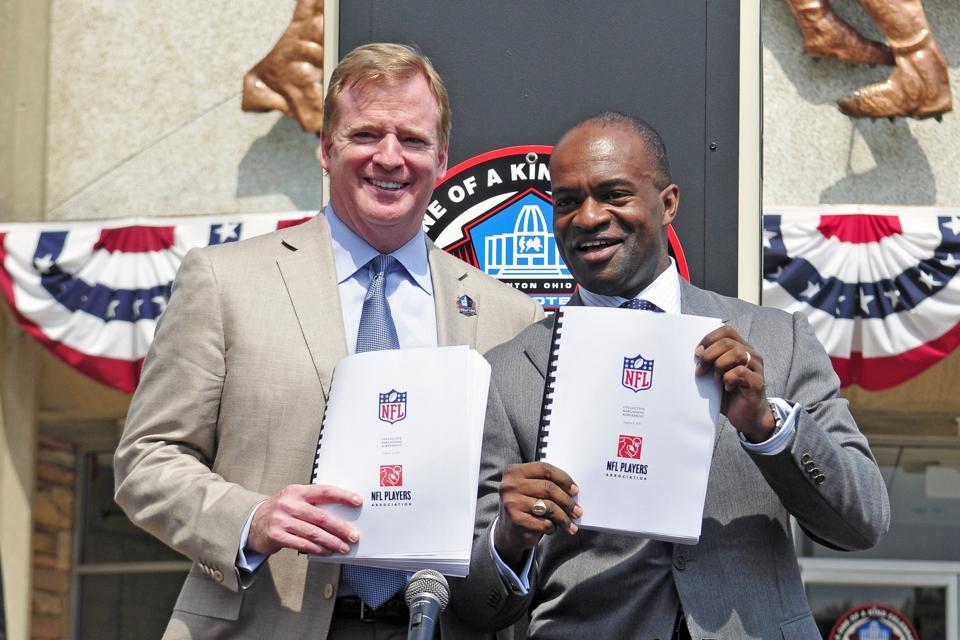

Getty Images

In 2024, there were 182 diagnosed concussions in the NFL, among the more than 1,500 players injuries diagnosed and tracked by NFL clubs each year. As would be expected, research has shown that former NFL players suffer from various medical afflictions at rates greater than the general population. And while players are generally well compensated during their careers (the minimum salary in 2025 is $840,000), careers are short (though not as short as the NFLPA claims). Consequently, it makes sense that NFL players have good benefits. Nevertheless, the benefits provided by NFL clubs – in large part as a result of demands by and negotiations with the NFLPA – are likely unmatched by any other company in America.

The Historical Context

The NFL and its players have the most contentious history of any of the major North American professional sports leagues. In 1970, the NFLPA gained formal recognition from the National Labor Relations Board to represent NFL players. That same year, it negotiated a new collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with the NFL that for the first time required NFL clubs to provide disability benefits, life insurance, and dental benefits.

Between then and 1993, the NFLPA and NFL waged near continuous litigation concerning the terms, conditions, and benefits of players’ employment. The players went on strike three times and filed numerous lawsuits against the league, alleging that its restrictions over player pay and movement violated antitrust law. CBAs were agreed to in 1977 and 1982 which marginally improved player benefits, but which did not yet provide players the right to free agency which by then existed in MLB, the NBA, and the NHL.

The players finally gained the right to free agency in 1993 as part of the settlement of litigation and in exchange for a salary cap. The 1993 CBA focused on the core economic structure of the league, a structure that generally is still in operation today. Indeed, then-NFLPA Executive Director Eugene Upshaw described his and then-NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue’s roles as “stewards of the game to try to ensure that we have stability and growth.”

During his Executive Director tenure from 1983 to 2008, Upshaw was never regarded as the most committed advocate for player health and safety. Upshaw was a bruising offensive lineman for the notoriously physical Oakland Raiders from 1967 to 1981. His tough-nosed play help the Raiders win two Super Bowls and got him elected to the Hall of Fame. Indeed, in 2007, amid increased scrutiny over the health of former players, Upshaw reportedly said he would “break” the “damn neck” of a former player that had criticized his leadership.

Change At The Top

Tagliabue retired in 2006, turning over leadership to current NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell. Upshaw unexpectedly died in August 2008 and was replaced as NFLPA Executive Director the next February by litigator DeMaurice Smith. Goodell and Smith were both hauled before Congress in 2009 to answer questions about concerning reports about the health of former players and the growing scientific consensus that concussions were far more problematic than the NFL’s Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee had previously claimed.

At the same time, the players and league were fighting over player pay and benefits and the Commissioner’s right to discipline players, among other issues. With that background, in 2011, after an offseason lockout, union decertification, and commencement of yet another antitrust lawsuit, the league and players agreed to a new CBA which substantially amended and supplemented player health, safety, and benefits provisions (for a longer history of the above-described events, see Chapter 7 of this report).

A Good Place To Work

The 2011 CBA was extended in 2020 and further improved player benefits. Today, NFL players are entitled to the following:

Termination Pay: Players with four or more Credited Seasons (seasons in which they were on the roster for at least three games) and who are released during the season are entitled to the unpaid balance of their salary for that season. Players may only receive Termination Pay once.Severance Pay Plan (first introduced in 1982): Players with two or more Credited Seasons automatically receive a lump sum payment 12 months after their last contract expired or was terminated for each Credited Season played, ranging from $5,000 for the 1989 season to $35,000 in 2025, and going up to $50,000 for the 2030 season.Retirement Plan (1968): Players with three or more Credited Seasons can receive monthly benefits of $836 per Credited Season payable at age 55. So a player with five years’ experience would receive a monthly payment of $4,180. According to the NFL, if the same player were to wait until age 65 to start his pension, his monthly benefit would be nearly $11,000 per month.Player Annuity Plan (1998): Players with at least one Credited Season can defer their compensation into an investment account to be paid out an annual basis after their career ends. Per IRS regulations, the maximum amount that can be deferred on a pre-tax basis in 2025 is $70,000.Second Career Savings Plan (1993): 401(k) plan that helps players save for retirement in a tax-favored manner. All NFL players are eligible and automatically enrolled, regardless of Credited Seasons. Clubs contribute $1,000 if the player has one Credited Season, $7,200 for two Credited Seasons, and $3,600 for players with three or more Credited Seasons. In addition, the club contributes $2 for every $1 contributed by a player up to a maximum of $34,000 per year pursuant to IRS limits. According to documents filed with the IRS, the plan has approximately 11,000 participants and $4 billion in assets available for benefits, having paid over $135 million in benefits in 2024.Player Insurance Plan (1968): Provides players and their immediate family with life insurance, accidental death and dismemberment insurance, medical coverage, dental coverage, and wellness benefits, including access to clinicians for mental health, alcoholism and substance abuse, child and parenting support services, elder care support services, pet care services, legal services, and identity theft services.Health Reimbursement Account (HRA) (2006): Helps to pay out-of-pocket healthcare expenses after players are no longer employed by an NFL club and any extended coverage under the Player Insurance Plan has expired. In 2025, teams contribute a nominal $45,000 per Credited Season to an HRA for each player, i.e., the money is not actually set aside but is a record of how much the teams promise to reimburse. Players contribute nothing.Long-Term Care Insurance Plan (2011): Provides medical insurance to cover the costs of long-term care for NFL players (but not their family members) with at least three Credited Seasons. The plan provides benefits of $150 a day for a maximum of four years.Former Player Life Improvement Plan (2007): Permits qualifying former players (and in some cases their dependents) not otherwise covered by health insurance to receive reimbursement for medical costs for joint replacements, prescription drugs, assisted living, neurological treatment, life insurance, and Medicare supplemental insurance.Disability & Neurocognitive Benefit Plan (1993): Players vested under the Retirement Plan can receive $40,000 to $48,000 in annual disability benefits, even if the disabling condition is unrelated to their NFL careers. Those benefits are increased between $4,000 and $6,000 in 2025 where there is neurocognitive impairment.The 88 Plan (2006): Reimburses or covers the costs for former players for care related to dementia, ALS, or Parkinson’s disease. The maximum annual benefits are $165,000. The plan is named for John Mackey, a Hall of Fame tight end who played from 1963-72, wore the number 88 during his career, and suffered from dementia before dying in 2011 at age 69.Tuition Assistance Plan (2002): Reimburses players for tuition, fees, and book costs associated with attending an eligible educational institution, including trade and vocational schools. In 2025, players with two Credited Seasons can receive up to $25,000 in reimbursements per year while players with at least five Credited Seasons can receive up to $85,000 per year.Workers’ Compensation: The CBA requires clubs to provide workers’ compensation benefits to its players, including similar benefits to players who play in states where athletes are exempted from workers’ compensation coverage, such as Florida.Non-Vested Former Player Wellness Plan (2020): Provides counseling and other support services for players not vested in the Retirement Plan as well as their household members and dependents. According to the NFL, “those looking for support can call 24/7 to get connected with resources for issues ranging from emotional health, childcare and more. Through this Plan, there is access to a dedicated concierge team that can assist the caller with appointment searches and/or appointment scheduling with a behavioral health clinician.”

Notably, these benefits are generally non-exclusive, meaning players can take advantage of many of them at the same time if they qualify. Moreover, there are additional programs and services designed to help future, current, and former NFL players, with particular focus on transitioning to a life after football.

In 2024, each club contributed approximately $80.294 million to the players’ total benefit costs, which also includes a collective $452 million in performance-based pay. For context, the 2024 salary cap was $255.4 million per team and, according to data from Sportico, NFL clubs averaged $692.3 million in revenue last year. Consequently, about 8.6% of club revenue and 23.9% of player compensation went toward benefit costs.

The Fine Print

There are of course many important contextual components to the above list of benefits. First and foremost, the list provides a short summary of lengthy and complex plans with far more nuance and detail than can be expressed here. Second, the process for applying and receiving benefits is a frequent subject of criticism and litigation, as many players and their attorneys have complained that it is overly bureaucratic and denies them benefits to which they are entitled. Third, the NFL is obviously a workplace with a high-rate of injury (see chapter 2 of this report), with particular concern for head injuries. Fourth, NFL careers are short – though not as short as is often presumed. The NFL and NFLPA have put forth their own data on that issue, but the only unbiased analysis known found a mean career length of 5.0 years for drafted players. And finally, the NFL is a cultural and financial juggernaut, with a reported $23 billion in revenue in 2024.

Better Than Most (Or Almost Everyone)

With all of that said, the NFL and NFLPA both deserve credit for providing what can fairly be described as the best benefits package of any private employer in America or close to it. The NFL’s $2 match for every $1 a player contributes to their 401(k) is exceptional, though not unprecedented (Visa, Biogen, and USAA reportedly also match 200%). Indeed, according to data from the Plan Sponsor Council of America, a non-profit trade association focused on retirement plans, only 2.7% of employers contribute more than dollar-for-dollar.

Not surprisingly then, Samantha Prince of Penn State Dickinson Law, an expert in company benefit plans, agreed that “NFL players are being taken care of much better than most employees out there.” She also pointed that there are many other jobs in which employees face high rates of injury, but that they do not have the same kind of benefits. Prince also identified the regular incremental adjustments in benefit amounts, auto-enrollment, protection against unilateral changes, and the NFL’s covering of administrative costs as valuable benefits provided in the NFL’s plans.

So while NFL players face extraordinary risks to their health, it should be at least somewhat comforting to know that they are entitled to extraordinary benefits for doing so.